Illustration by Madalina Pavel (Picturise)

25 years of the Youth Partnership

by Howard Williamson

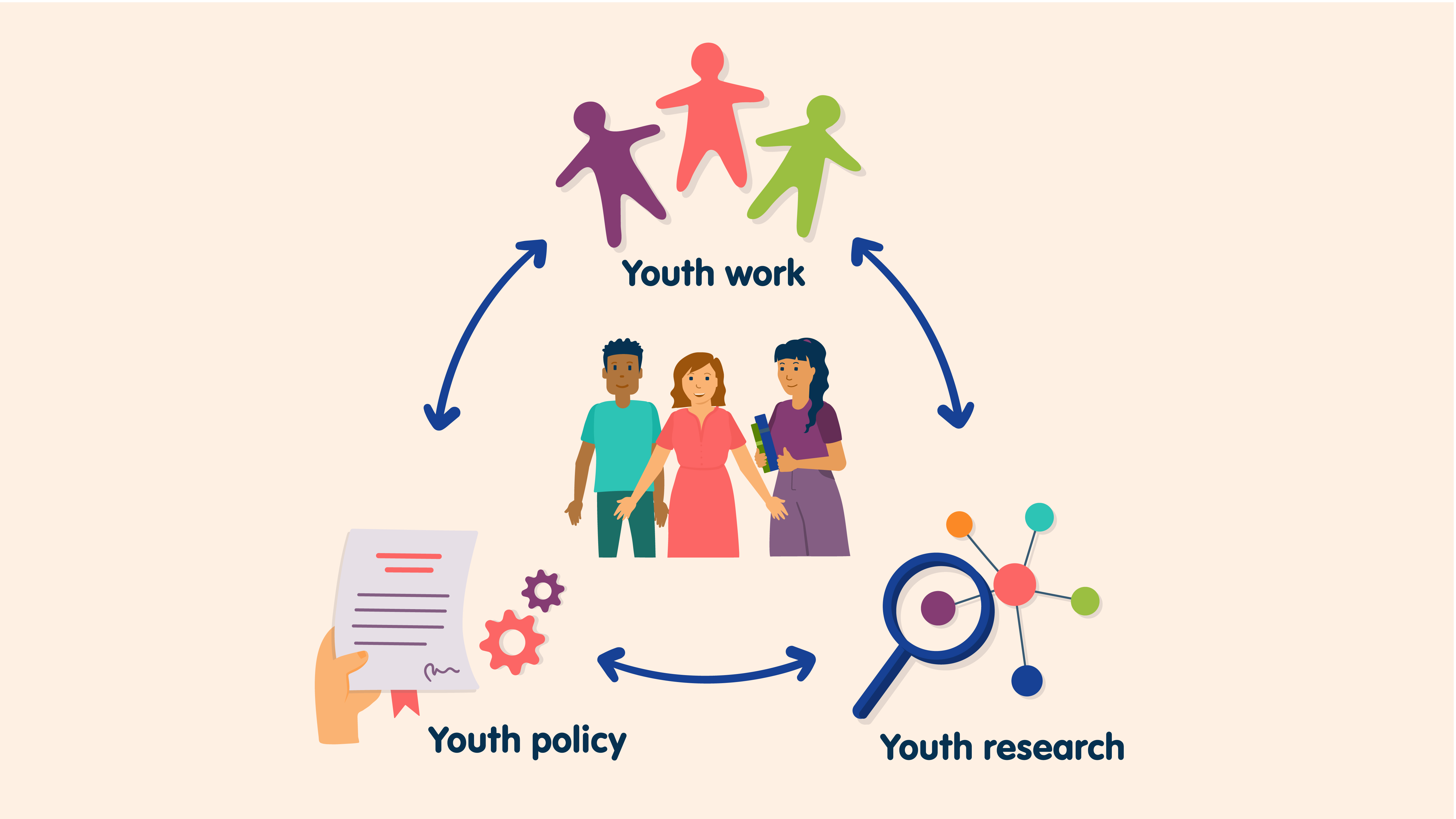

As the European Knowledge Centre for Youth Policy (EKCYP) was launched by Bryony Hoskins in 2005 during the Luxembourg Presidency of the Council of the European Union, the “magic triangle” of youth policy, youth research and youth (work) practice appeared. It was captured in the book that arose from that presidency, called Dialogues and networks (Milmeister and Williamson 2006).

Unknown to me, I had always been the triangle – a youth worker since the 1960s, a youth researcher since the 1970s and a youth policy adviser and expert since the 1980s. And in the decade after that, in 1998, the Director of the Council of Europe Youth Directorate, Lasse Siurala, called me to invite me to be part of the Steering Group for a new partnership – the EU–Council of Europe partnership in the field of youth.

At the start, the Youth Partnership, as it came to be known, had a solitary purpose and responsibility: the training of youth workers at a European level. To that end, co-chaired by two German men (Peter Lauritzen and Frank Marx) who beyond their nationality and gender were like chalk and cheese yet somehow complemented each other very well, the Steering Group watched over the development and implementation of the Advanced Training the Trainers in Europe (ATTE) course.

I spoke at the very end of the ATTE course, in the European Youth Centre Budapest (the ATTE course in its wider context, final “celebratory” lecture to the first graduates of the ATTE, October 2003), and foreshadowed the triangle, arguing that we needed a course at European level that might bring together “people like me”, of whom there were a growing number, who personified various combinations of youth research, policy and practice. [This eventually came to fruition, at least as a pilot course in 2013, in the MA in European Youth Studies, which had been partially supported throughout its evolution by the partnership.]

And, slowly, the Youth Partnership came to embody the triangle. Soon after its inaugural “training” responsibilities, it also took responsibility for Euro-Mediterranean co-operation (essentially a policy role of transnational, indeed transcontinental exchange) and research. Youth research had had a minor presence within the Council of Europe since the mid-1980s and a slightly stronger presence in the early 1990s with the formation of a network of youth researchers to support the newly appointed Research Officer (Irena Guidikova) in the Council of Europe Youth Directorate. In 1997, the European Commission had conducted a study of “citizenship with a European dimension”, focused significantly, though not exclusively, on EU youth programmes (see European Commission 1998). At the end of the 1990s, the Council of Europe had also collaborated with the International Sociological Association’s youth research committee (rc34) to deliver three (1999-2001) young researchers’ seminars at the European Youth Centre in Budapest. It was through a participant at the last of these seminars, Bryony Hoskins, that the idea for a European Knowledge Centre for Youth Policy sprang, while another participant, Filip Coussée, was the intellectual driving force behind the History of Youth Work in Europe project.

The relatively recently formed Youth Partnership first set about strengthening its research role through supporting what was known as the European Network of Youth Research Correspondents (which I chaired). The network met once a year. Correspondents were nominated by member states of the Council of Europe. This nomination process, though democratic, was a problem! Nominations were sometimes bona fide researchers but they were also often junior civil servants or administrative personnel with little knowledge or interest in research, to the chagrin of authentic researchers who attended (the two “survivors” who are still active through the Pool of European Youth Researchers (PEYR) are Manfred Zentner and Marti Taru). Meetings tended to be governed by little more than the presentation of current developments in the Youth Directorate of the Council of Europe, the Youth Unit within the European Commission and, of course, the Youth Partnership. There was little attention to research, either reactively or proactively. It was an exercise in considerable frustration, serving few needs and satisfying few people. Few were disappointed when the network was closed down in 2008.

Out of those ashes rose the Pool of European Youth Researchers, a smaller and sharper group, selected following a call of unequivocally research-experienced and research-focused individuals who have played an important part, individually and collectively, in the development of a research agenda within the Youth Partnership to this day. The PEYR complemented the work of the national correspondents for the EKCYP, whose role was to furnish the Youth Partnership with a range of material relevant to the youth sector from their national contexts. As European Commission official Nathalie Stockwell had said at the launch of the EKCYP in Luxembourg, the acronym should be pronounced as “équipe” – a team that would produce knowledge and understanding of European youth, one of the four aspirational planks of the EU White Paper on youth that had been launched at the turn of the century (under Belgium’s Presidency of the Council of the EU, in November 2001).

The framework for the PEYR was shaped immediately after the first seminar on the history of youth work in Europe, held in Blankenberge, Belgium, in 2008. It was the first of seven seminars (each of which led to a publication), convened over almost ten years and supported by the Youth Partnership, as indeed was the thinking behind the establishment of the European Youth Work Conventions, the first of which was held in Belgium (in Ghent) in 2010. These were the first seeds of growth for a European agenda for youth work, supported by the Council of Europe through its Recommendation CM/Rec(2017)4 on youth work in 2017 (the political output of the 2nd European Youth Work Convention) and consolidated in 2020 through the European Union’s Resolution on the Framework for establishing a European Youth Work Agenda, which preceded the 3rd European Youth Work Convention. One can almost feel the Youth Partnership’s place at the heart of these networks, activities and relationships.

Policy issues were more of a slow burner in the evolution of the Youth Partnership’s work programmes. Both the European Commission and the Council of Europe had their own distinctive youth sector priorities that sometimes converged and at times remained quite separate. The Council of Europe had established its international reviews of national youth policy in 1997 and, over the next 20 years, reviewed 21 European countries. These were synthesised in three volumes entitled Supporting young people in Europe (see Williamson 2002, 2008, 2017). The EU had launched its White Paper on youth in 2001 with its four themes of participation, information, voluntary activities and a greater understanding of youth. During the next decade, the EU also promoted its European Youth Pact (2005) and its first dedicated Youth Strategy: “Investing and Empowering” (2009) with ten “fields of action”, and the Council of Europe concluded a ten-year plan in “The future of the Council of Europe youth policy: AGENDA 2020” (2008). Youth policy appeared to remain somewhat segmented and separately a domain within each of the two institutions that guided and governed the work of the Youth Partnership.

Yet, increasingly, the Youth Partnership was asked to take responsibility for elements of youth policy and was given a wider brief – through the EKCYP and PEYR – to research aspects of European youth policy and to explore how such policy was translating into and having an impact on practice at a national level. It has subsequently played a key role in making the connections between policy, research and practice on issues such as learning mobility, work with minorities, digitalisation and – perhaps above all – youth work.

Of particular note in terms of forging those connections between the corners of the “magic triangle” have been the annual symposiums that have been at the heart of the Youth Partnership’s work plans, covering different topics each year but bringing together participants from across the youth sector and culminating in a report that, in my view, has captured the contemporary state of play on that particular topic.

Moreover, the Youth Partnership has built a body of knowledge around the youth sector in Europe through work it has commissioned and subsequently published. The Youth Knowledge Books (a name I suggested when the PEYR was first discussed in 2008), usually available both in hard copy and online, are today an important catalogue of reference material for those in the field of youth. Examples include an analysis of youth work policy goals and a study of the education and training of youth workers in Europe. The Youth Partnership has also been responsible almost since its start for the production of Coyote, a magazine that has provided accessible information and dialogue on thematic issues relevant to the youth sector, shining both a serious and sometimes more humorous light into all corners of the triangle. You are reading the latest copy now!

Notwithstanding what have been, arguably, other aspects of youth policy convergence between the two institutions, there has been unequivocally growing consensus in relation to youth work. This has permitted the Youth Partnership to take on a central role in supporting the evolution of youth work across Europe. One might even claim that it was the Youth Partnership that first helped to get the ball rolling through its support for the History of Youth Work in Europe seminars and publications, and the Youth Work Conventions, so the process has come full circle. Youth work was, for the first time at a European level, on the political landscape, starting with an EU Resolution on youth work in 2010 and followed by the Council of Europe’s recommendation on youth work (see above). Both flowed from the final declarations of the first two European Youth Work Conventions. This evolution was consolidated by the inclusion of youth work, albeit in different ways, in the subsequent EU Youth Strategy (2018) and the Council of Europe Youth sector strategy 2030 (2020). In the former, youth work was a key methodology for supporting one of its three strategic pillars (Engage, Connect, Empower); in the latter, youth work was one of its four thematic priorities (Revitalising democracy, Access to rights, Living together in peaceful and diverse societies, Youth work). And, following on from this, there was undoubtedly more robust and dedicated attention to the place of youth work across Europe and within European youth policy.

The political Resolution on the Framework for establishing a European Youth Work Agenda, through an EU document agreed under Germany’s Presidency of the Council of the European Union, was quickly transformed into a “Bonn Process” catalysed by the Declaration of the 3rd European Youth Work Convention, relating to all 50 countries that participated in the convention. Germany also had the chairmanship of the Council of Europe at the time. The declaration argued for strengthened co-operation between the European Commission and the Council of Europe and for improved networks and co-operation, with convention participants acknowledging that “the EU–Council of Europe partnership in the field of youth has already had a significant coordinating role in many of the activities on youth work in the European context” (p. 18). Taking its lead from this appreciation, the Youth Partnership proceeded to form a Steering Group for the European Youth Work Agenda, composed of individuals from all corners of the magic triangle or what had now come to be known as the youth work “community of practice”.

I started my professional life as a local youth worker and later, working with young offenders, I completed a doctorate in the field of juvenile justice, became a parliamentary adviser on education and a policy expert across the youth fields of employment, health (substance misuse) and criminal justice. Though I despise the terminology, I am sometimes described as the “founding father of the NEETs”, having first written about young people not in education, employment or training in the 1980s (from a youth work perspective), carried out the first analysis of the group in the early 1990s (from a research perspective) and then advised on relevant programmes and interventions (from a policy perspective). During that time, I became involved with the Council of Europe (in 1985) and the European Commission (in 1988), bringing my triangular views from my UK experience to the European table.

The Youth Partnership epitomises everything I stand for, as we endeavour to persuade youth researchers that they need a stronger grasp of youth policy and practice, youth policy makers that they need more sensitivity and responsiveness to youth research and practice, and youth workers that they need more engagement with youth policy and research! That is how I have spent the whole of my working life, of which I am deeply appreciative that half of it has been travelled benefiting from and contributing to the work of the Youth Partnership.

I may not travel much further with the Youth Partnership but I hope it will consolidate its role at the fulcrum of connections between the European Commission and the Council of Europe, making its contribution to all three corners of the “magic triangle” and supporting the youth sector community of practice throughout Europe to build its profile and capacity and to secure great visibility and recognition, deep into the future.

Penblwydd Hapus (from Wales), dear Youth Partnership,

Howard

References

References

European Commission (1998), Education and active citizenship in the European Union, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Milmeister, M. and Williamson, H. (Eds) (2006), Dialogues and networks: Organising exchanges between youth field actors, Youth research monographs Volume 2, Luxembourg: Editions Phi.

Williamson, H. (2002), Supporting young people in Europe – Principles, policies and practice, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Williamson, H. (2008), Supporting young people in Europe – Volume 2, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Williamson, H. (2017), Supporting young people in Europe (Volume III) – Looking to the Future, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Howard is a professor of European youth policy at the University of South Wales (UK). He is also a qualified youth worker, a senior youth policy adviser, soccer coach and referee, motorcyclist and guitar player.