Context matters: exogenous reflection on the EYWC

by Lamin Darboe

19/06/2021

At the beginning – power of networking

At the beginning – power of networking

Sometime in August 2020, I received an email from the Commonwealth Youth Programme addressed to youth directors with the subject “Urgent – Essentials of Youth Work (MOOC): 1st Sep – 18th Oct 2020”, inviting me to sign up for this Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) organised by the youth partnership of the Council of Europe and the European Union. As the Executive Director of The Gambia National Youth Council, I signed up for the online course, and as usual, trailed the Council of Europe-EU youth partnership web page and links to familiarise myself with the course context and to satisfy my curiosity as well. The 3rd European Youth Work Convention (EYWC) pop-up on my Facebook search appeared when they shared the Council of Europe-EU youth partnership call for enrolment in MOOC on Essentials of Youth Work. The Youth Work Convention caught my attention; I skimmed and further came across their call for rapporteurs and facilitators. I got excited and interested in this mega European conclave on youth work, but later convinced myself that the event and the call weren’t for me. It’s for Europeans, I concluded. What I never knew was destiny has a different plan for my involvement.

Sadly, I could not take part in the MOOC on Essentials of Youth Work due to numerous commitments such as Covid-19 Risk Communications and Community Engagements in the Gambia coupled with my preparations to travel to England for master’s studies, among others. I travelled to the UK and arrived at the University of Sussex, Brighton in mid-October 2020, amidst a global pandemic; I had to self-isolate. This was an opportunity, I reckon, to announce my presence, get a little loud about my Chevening Scholarship and reach out to my valuable contacts list in the UK. On top of this list was my revered Professor Howard whom I was introduced to and met in March 2019. I had a Sunday conversation with Howard Williamson – Professor of European Youth

But why was I attracted to this convention? May be the saying “magnets attract irons” answers that for me, or simply put “you are what you attract” explains the forces better. I am a youth worker, attracted to anything youth! And the European Youth Work Convention was no exception. I served as a youth work volunteer in the remote villages of the Gambia organising remedial classes for underprivileged children, co-founded a community library for learning and as safe space for vulnerable children and youth, led a community youth club on health promotion and education of youth at risk, and organised summer sports events called Nawettan as a tool to mobilise, organise, and for well-being. As a youth leader, I co-founded a district-wide children and youth association advocating for voice, space and representation of young men and women, and subsequently got elected as Secretary to the Regional Youth Committee. By extension, I became a trained

I rose through the ranks to become the Executive Director of the National Youth Council of the Gambia where I worked on youth programming, strategic planning and youth policy in the Gambia, and was also involved in international youth work practices in Africa. This interest never dwindles to date – it’s a lifestyle for me.

At the convention – difference in similarities!

At the convention – difference in similarities!

My aspirations of furthering and enriching youth work experiences for several young people I worked with, and previous engagements in the youth work practices and policy spaces at grass-root, national, regional and at continental levels sharpened my hunger to learn from other experiences and practices. The 3rd European Youth Work Convention provided me with the opportunity to observe and engage with actors and youth work practitioners in Europe, and as an opportunity to reflect on youth work practices and policies back home. At the conclave, I observe the similarities of youth work practices in Europe and Africa, the Gambia in particular. The energy and passion, actors and institutions, the ambitions and hope, the fears and uncertainties were quite familiar. At the heart of acquisition lie the differences – the access, technology, the community of and in practice, and normative structures and opportunities. Then I recalled, context matters, but how?

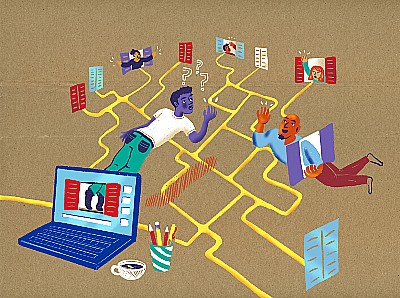

Firstly, upon registration, my expectation was to receive a follow-up email with a Google Hangout, Zoom or Microsoft team’s link to the convention. These are platforms I am familiar with in hosting meetings, webinars and conferences. They had become the new norm of the Covid-19 era and I had utilised them more than I’d ever expected in 2020. I was already Zoom-fatigued, after my intense first semester master’s programme at the University of Sussex and was wondering whether I could keep up with another protracted Zoom meeting. I am familiar with events apps used in events management in Gambia, Africa and elsewhere. For example, the Annual TAF Conference (TAFCON) in the Gambia, UN Habitat World Urban Forum (WUF10) in Abu Dhabi, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Nairobi Summit on ICPD+25 and other UN meetings where I had interacted with event apps and platforms. But this time it’s not any of the above apps, but the Eventspace platform. This platform provided me with a new insight into convening in the digital space.

That was acknowledged but it wasn’t my main concern. The question that kept ringing in my head was, can I replicate such a magnificent event in the Gambia or in Africa with rural grass-roots youth work volunteers? The answer was obvious. The privilege of sustaining the internet and electricity using the Eventspace platform will be a luxury and far-fetched for most participants. The limitation of digital poverty in the Gambia and by extension most African countries is acute in the rural areas, especially among local youth work volunteers. The lack of basic development services such as electricity and the internet, coupled with cost and affordability only makes such dreams unattainable, despite the similarity of purpose to serve youth. The context differs.

Thirdly, in my reflection, I recognised the role of government, civil societies, educational institutions, and individual volunteers as valuable actors in achieving together the ambitious goals of the declaration and the objectives of the European Youth Work Agenda. This highlights the importance of actors and stakeholders operating as a “community of practitioners” to co-ordinate and co-operate, within the geography of European borders as a community in practice. This facilitates and supports the mobility of youth and youth workers as necessary to enhance exchange and interchange of knowledge, skills improvement, attitudes and values across borders and spaces within Europe. The major differences with the African youth work landscape are the fragmented community of practices confined to nation states and regions. The national borders crafted by European colonisers have continued to limit the continent’s sense of community in practice with far reaching implications on immobility of youth and youth workers, resulting in limited exchange and interchange of youth work knowledge, skills and values as enjoyed elsewhere in Europe. The enduring entanglement created by immobility dilemmas and hostilities on irregular migration limits their choices and obscures their access to life and livelihoods skills and opportunities. This unrealised right to movement for some of these youth and youth workers in the 21st century globalised world inhibits the realisation of the full potential of youth and youth work, and further contributes to the reproduction of poverty and inequality in Africa.

Post-convention – communication and commitment!

Post-convention – communication and commitment!

Following the conclusion of the convention, the sustained communications of the outcome was impressive. I followed it on the app, traditional and new media channels and websites. The timely availability of the outcome document speaks of the dedication behind the scene and the importance attached to the moment. It also means all participants can access the results of their efforts, and actors and stakeholders can have direct access to the outcome document for accelerated programme planning and implantation.

The Bonn process is both complementary to and clarifying for the ambitious goals of the European Youth Work Agenda. I find the declaration to be rich and broad-based, evolving from a quality consultative process and engagement of both actors and beneficiaries of the youth work practices. It is strategically aligned to the EU youth strategy and the Council of Europe youth sector strategy. It encompasses the aspirations of both youth work from the ground and from above, with emphasis on quality development and its socio-economic and political implications. It demands policy and strategic reforms and alignments that prioritise increased resources allocations to youth work, especially local youth work practices and capacity building, and improve co-ordination and cross-sectoral co-operation to enhance recognition, innovation, and the networks young people deserve.

In the face of globalisation, the rising polarisation of society and democratic backsliding coupled with other Covid-19-induced boundaries and limitations, it will be interesting to learn how these ambitious outcomes are aligned and delivered within the global youth work discourse.

The main lesson for me, notwithstanding the aspirations and commitments to deliver a safe and rewarding community for and with our youth in Africa and Europe, was that context really matters in the pathways!