Illustration by Daniela Nunes

Youth work for sustainability

by Esther Vallado

A lot has been written already about sustainability and youth work. The Youth Partnership has produced a T-Kit about it (T-Kit 13), and a sustainability checklist, among other great resources on the topic compiled by Asociación Biodiversa. When prompted to write a short article for this issue of Coyote I asked myself: regarding sustainability, what would be useful for youth workers, trainers, youth policy makers and researchers to know?

As an environmental scientist, environmental organisation manager, climate activist and youth worker focusing on education for sustainability for more than a decade, too many answers come to my mind when pondering this question. This is what I consider essential for you to know, including tools and methods that you can use to support sustainability in your work with young people:

Sustainability is essential

Sustainability is the ability to maintain the conditions that allow life on Earth as we know it. In this sense there is barely anything more important than that. Sustainability equals survival. It is often mentioned that sustainability has three dimensions: social, economic and environmental. However, we generally focus on the environmental aspects, and this is for a reason. Environmental sustainability is a prerequisite for social and economic sustainability. Societies exist within an environment which, if it is healthy and balanced, provides enough for every living being and conditions for peaceful co-existence. Our economy is largely reliant on the provision of natural resources and the indirect services that healthy ecosystems provide. It is difficult to imagine a sustainable economy on a dysfunctional planet. It may be possible, but would it be desirable?

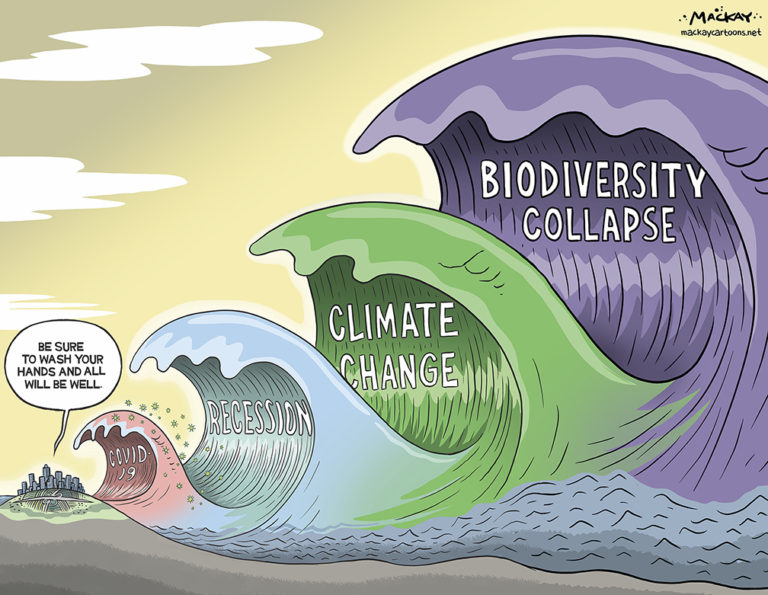

It’s not all climate change

Pretty much everyone has heard about the threats of the climate crisis by now, or has directly experienced its consequences. The climate regulation capacity of our planet is clearly impaired as a result of human actions. Climate regulation is, however, just one of the many Earth processes which create the conditions for life to be possible, and that is currently being pushed beyond its safe operational limits.

Scientists have identified a total of nine planetary boundaries. These are processes that regulate the stability and resilience (the capacity to recover from a perturbation) of the Earth system. Crossing these boundaries increases the risk of large-scale abrupt environmental changes that could eventually render our planet inhabitable, at least for us humans. Climate change represents just one of these nine boundaries, the others being biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater change, biogeochemical flows, ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion and novel entities. Out of the nine, six are in overshoot, meaning that we have exceeded its safe limits.

So climate regulation is not the only life-sustaining process there is, nor even the one that’s faring the worst. Quoting scientists at the Stockholm Resilience Centre: “Boundaries are interrelated processes within the complex biophysical Earth system. A global focus on climate change alone is not sufficient for increased sustainability. Instead, understanding the interplay of boundaries … is key in science and practice.”

Source: mackaycartoons.net

The way we live is not sustainable

Do you know how many planet Earths we would need if everyone lived the way in which you currently do? You can find out by calculating your ecological footprint (the impact that your daily activities have on the planet’s health). It is good to know which of your life choices have a bigger impact on the state of the planet.

The systems on which our societies run (economic, education, political, social, manufacturing systems, etc.) have been designed from a mind-set that largely ignores how fundamental it is to preserve the Earth systems that support life on this planet. This leads to the unintended promotion of unsustainable practices throughout all the spheres cited above: economic, educational, political and so on.

What are the root causes of the current unsustainable lifestyles?

The nature of these causes is systemic. According to systems thinking theory, people are only responsible for 20% of their actions, the other 80% is due to the systems which are in place. People tend to do what is easiest for them, what is facilitated by the systems around them (e.g. if there is a rubbish bin very close to where we are, a majority of us will throw our rubbish there. If it’s far, only a minority will go the extra mile to throw it there).

But what are the root causes of our failure to live in sustainable ways?

The predominant anthropocentrism

A philosophical view that argues that human beings are the central or most significant entities in the world. Anthropocentrism regards humans as separate from and superior to nature, and holds that human life has intrinsic value while other entities are resources that may justifiably be exploited for the benefit of humankind. This is a basic belief embedded in many Western religions and philosophies (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica).

Such beliefs have resulted in systems that are unsustainable, as they ignore the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things on Earth.

Eco-illiteracy

Eco-illiteracy is the lack of knowledge and understanding of the natural systems that make life on earth possible. Its opposite, ecoliteracy, means understanding the principles of organisation of ecological communities (i.e. ecosystems) and using those principles for creating sustainable human communities.

If the majority of us were ecoliterate we, most likely, wouldn’t be facing the current ecological crisis.

A crisis in values

Values represent our guiding principles: our broadest motivations, influencing the attitudes we hold and how we act. The values being portrayed and fostered in the mainstream media in the early 2020s are mostly about wealth, power, ambition, public image, social recognition, achievement, hedonism and so on. Social media posts, advertisement campaigns, and even job openings encourage and praise these values. All of these are extrinsic values, centred on external approval or rewards. The documentary “the social dilemma” gives more information and food for thought on the effects of mainstream social media on society as it portrays and fosters extrinsic values.

These values that are so eagerly being fostered are the exact opposite of the ones that would encourage environmentally-friendly behaviours and concern about social justice. I recommend reading the booklet “Common cause for nature” for more information on values and the different kinds of behaviour that they influence.

A disconnection from nature

The majority of Europeans (around 70%) live in urban or semi-urban environments, far away from wild nature. In towns and cities, food doesn’t come from the soil, but rather from supermarkets; fun and enjoyment happens mostly in shopping malls, cinemas and the like, and not in forests, fields, mountains, rivers or beaches. This artificial distance between us and wild nature exacerbates our anthropocentric world-view, as we perceive ourselves separated from (the rest of) nature.

This perception has unsustainable behaviours as a consequence. Why would we take into account in our decision making that which we don’t know, value or feel connected with?

An interesting read about the consequences of this disconnection on our capacities and our well-being is the best-seller Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, where he describes what he calls the “Nature deficit disorder”. Here’s an interesting interview with him tackling these topics.

A disconnection from ourselves

Being so focused on the online (and offline) identities that we portray we, and particularly young people, lose touch with who we really are, in favour of who we are expected to be, do, wear, listen to, go to, etc. This disconnection makes it difficult to be aware of our real selves and identify what values we really want to stand for. In our pursuit to fit in with a “perfect” identity, we move away from acknowledging our human nature, our whole selves (dark sides included), and we create filtered out artificial versions of ourselves instead.

From that standpoint, we cannot connect to each other meaningfully nor attain the intrinsic values that would motivate us to act sustainably.

How can we support sustainability through our work with young people?

Although the root causes of our unsustainable behaviour are very deep and may seem insurmountable, there are many ways in which each of us, and particularly those of us working with and for young people, can contribute to supporting the shifts that are needed in order to reach sustainability:

Recover ecocentrism

Ecocentrism, understood as a nature-centred world-view, with its resulting nature-centred value system, is a key pathway to sustainability. Trainers, youth workers, youth policy makers and researchers alike can all contribute to popularising this philosophical view. We can educate ourselves and others about it, design projects, activities and policies for and with young people having this view in mind, and continue the ongoing research into the importance of this world-view in solving our unprecedented environmental crisis.

Pursue global ecoliteracy

As youth trainers we can design learning experiences for developing competences for sustainability. One of the tools we can use for this is the European Sustainability Competence Framework, better known as GreenComp.

Other ideas on how to do this can be found in the specific article on ecoliteracy that you will find in this issue of Coyote.

Portray and foster intrinsic values

Kindness, compassion, co-operation, equality, social justice, benevolence, loyalty, humbleness, honesty, wisdom, etc. are all intrinsic values (values that are inherently rewarding to pursue). These are closely related to environmentally-friendly behaviours and concern about social justice.

As trainers and youth workers, we are role models. If we live by these values, our example will permeate to the young people we work with. We can also organise learning experiences that work directly with these values. One useful resource for this is Value Cards, which can be used to support reflection about personal and/or professional, individual and group values.

Foster nature connection

There are plenty of tools and methodologies that youth trainers can use for fostering nature connection among the young people we work with. Some of them are:

- The Work That Reconnects, by Joanna Macy, based on deep ecology, is a four-step process which includes many different experiential activities aimed at increasing our sense of connectedness with nature;

- Solo in nature, a conveniently guided and monitored “solo” experience in nature of varying length (from 1 hour to 24 hours or more) followed by a collective experience-sharing and debriefing;

- Forest bathing, the practice of immersion in a forest through different activities that enhance the senses and increase perception, leading to a state of relaxation and appreciation;

- ”Earthing” or “grounding”, the practice of walking barefoot on natural surfaces;

- And all of those included in the Coyote’s Guide to Connecting with Nature (nothing to do with our Coyote but equally useful!).

Encourage connection to ourselves

By using different types of guided meditation, self-reflection and self-awareness practices, youth trainers can help young people recover their connection with themselves. The Work that Reconnects mentioned above includes a number of self-reflection and self-awareness practices. Another method that we commonly use for this in youth training is the Way of Council, which also trains other competences that are very useful for community living, such as deep listening, empathy, the ability to communicate the essence, etc. Other methods worth exploring are those detailed by Bill Plotkin in his book Soulcraft.

This can help young people find their real selves, beyond the fictional characters that they are called to interpret. It can also help them discover the real values that they want to pursue, those that will give meaning to their lives. And it can, at the same time, transform them into eco-responsible individuals ready to connect to others and create the change they want to see in the world.

In this article I have described some essentials around sustainability, the causes behind our unsustainable lifestyles, and outlined some of the methods and tools available for youth trainers and youth workers to help achieve sustainability. Youth policy makers and researchers also have a big role to play in the paradigm shift that is needed: from an unsustainable society to a life-sustaining civilisation. It is no small task and we need everyone on board.

Quoting Joanna Macy:

A revolution is under way because people are realizing that our needs can be met without destroying our world. We have the technical knowledge, the communication tools, and material resources to grow enough food, ensure clean air and water, and meet rational energy needs. Future generations, if there is a livable world for them, will look back at the epochal transition we are making to a life-sustaining society. And they may well call this the time of the Great Turning. It is happening now.

There are many ways in which we – particularly those of us working with and for young people – can contribute to support this transition to a life-sustaining society. Let’s embrace this responsibility and be the ones leading the change that we need.

Esther is a freelance trainer and facilitator specialised in environmental issues, sustainability, and connection with nature.