Illustration by Madalina Pavel (Picturise)

Youth transitions

by Maria-Carmen Pantea

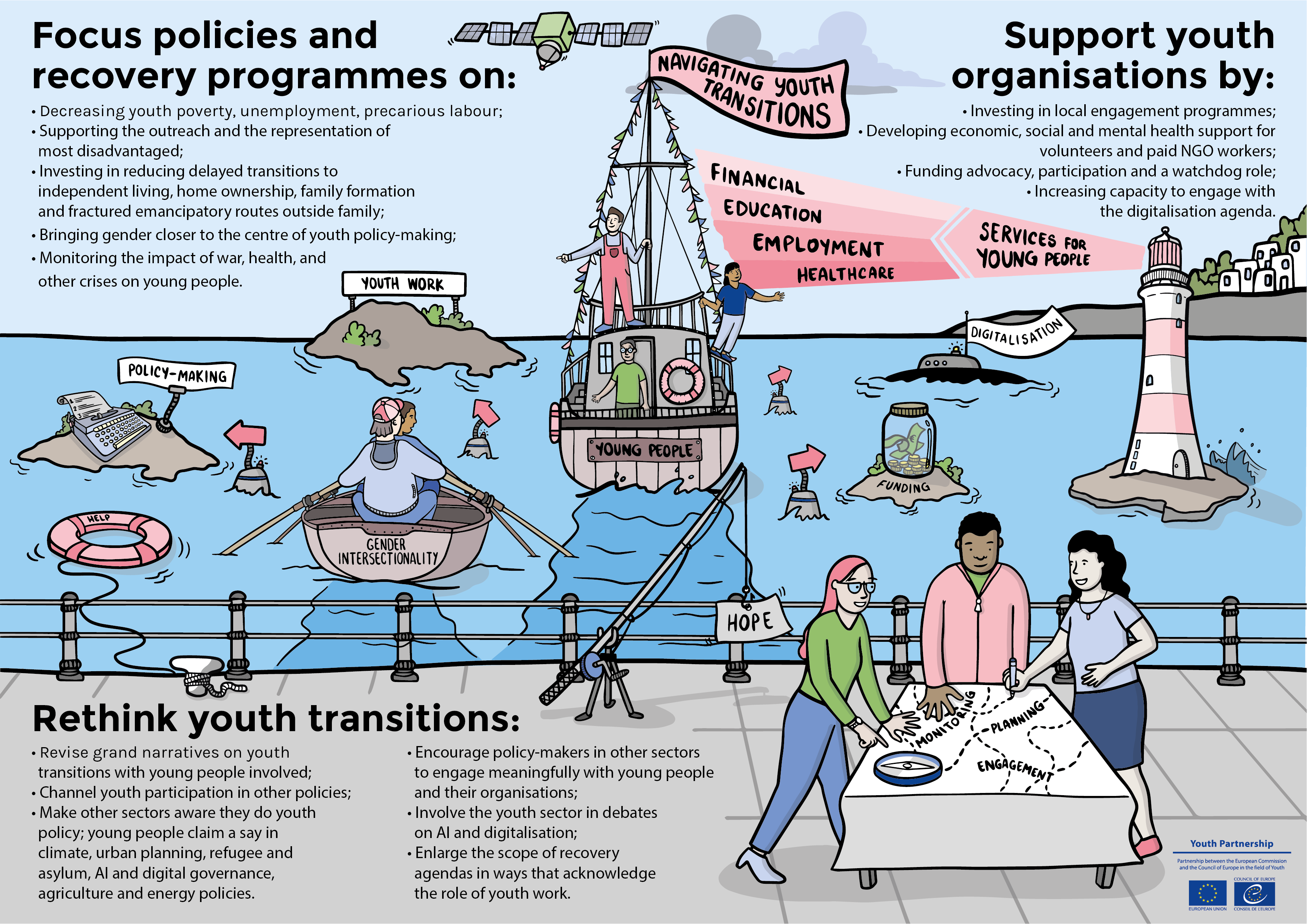

In an age when young people expect to find their own individualised paths, it is important to frame youth transitions, not only as a personal process, but also as a matter of public policy. For 25 years, the Youth Partnership has been engaged in such processes. This is even more important as, in many countries, the “home” policy for youth-related issues is continuously on the move: governmental departments are being merged, dissolved or relocated, or are experiencing their own institutional transitions. There are obvious limitations to these processes (including a shorter institutional memory). But these institutional restructurings also have some benefits, as diverse administrations have to think about the impact of their policies on young people. This article summarises some of the activities and resources developed by the Youth Partnership in the last two years. It shows that it worked to consolidate the knowledge on previous actions, but also to open up emerging policy agendas and views on youth.

A major priority after the pandemic was to integrate youth work in Covid-relief responses. Given the overemphasis on the economic dimensions of the recovery, the Youth Partnership strived to advocate for an inclusive recovery agenda in ways that not only integrate economic responses, but also the social dimension and youth development. Conventionally, youth transitions are at the intersection of education, employment, housing and welfare. Increasingly, however, other policy fields not traditionally associated with young people (e.g. climate, AI, urbanisation, transport, energy) do have implications for them. Making other policy sectors aware they are also engaged in youth policy making is an emerging challenge. This powerful message has been prevalent in several meetings, including the Youth Partnership’s 2022 symposium.

Youth services during Covid-19 – what have we learned?

Youth services during Covid-19 – what have we learned?

The report on youth services during the pandemic (Potočnik and Ivanian 2022) started from the observation that the pandemic had stretched the capacity of youth services, provoking innovative responses and highlighting weaknesses and structural challenges, notably a loss of funding and brain drain. Yet, the use of recovery funds for alleviating the impact of the pandemic on youth services was modest, at best. The report called for investment in all state-operated youth services and also in the services provided by civil society organisations. It called for governments and educational institutions to set up mechanisms and structures for the recognition of youth work. Those who have been longer in this field may remember lengthier debates around this issue, especially in view of the diverse youth work legacies in Europe. It seems we are now getting closer to a more unified way of looking at what makes a youth worker. Or not?

Young people’s access to rights – where are we five years since the recommendation?

Young people’s access to rights – where are we five years since the recommendation?

The review of young people’s access to rights and non-discrimination (Potočnik 2021) suggests that, while young people are more sensitised to discrimination and violation of human rights than older citizens, they still face discrimination mainly in education and employment. The review concludes that 2016 was a year of many political advancements, as countries committed to the Council of Europe’s recommendation on young people’s access to rights (CM/Rec(2016)7). Previously, “being young” was not recognised as grounds for discrimination. This has been redressed by Article I.1, yet the ambition was short-lived as the review of the recommendation’s impact several years later shows that countries did not convincingly incorporate young people’s access to rights and the importance of tackling discrimination in their policy documents. During the Covid-19 pandemic the “repertoire of restrictions” for limiting young people’s access to rights was enlarged, as the restrictions generated by the pandemic were sometimes used for less legitimate reasons (Pantea 2021).

Political rights and freedom to assemble – backsliding in many countries

Political rights and freedom to assemble – backsliding in many countries

Written in the first year of the pandemic, another Youth Partnership study on young people’s right to assemble peacefully aimed to prepare the ground for the first review of the recommendation on young people’s access to rights (CM/Rec(2016)7, Article I.2). It found that while the literature and reports are generally concerned with formal organisations, barriers to the right to assemble often target informal manifestations of civil society, notably protests. However, not all youth organisations and young people taking part in civic life are affected and not all in the same way or to a similar degree. Some are better equipped than others to navigate unfriendly environments or to take action when threatened. Some are not endangered at all (see also Deželan et al. 2020 for a detailed mapping of the threats to the civil sector).

Important elements of risk for youth organisations are related to the geopolitical context (e.g. organisations from the post-Soviet bloc); the unstable economic environment, with weak fundraising cultures and possibilities to raise domestic funds; and their mission (those focused on providing social services or active in “non-controversial” issues are less affected). The size, structure and professional capacity of organisations matter, as large umbrella organisations that are internationally represented are better able to navigate and negotiate the terms of their involvement, than grass-roots, youth-led organisations with short institutional memory and high turnover. Ultimately, the membership composition brings an important element of risk for organisations working with migrants and refugees, Roma and LGBTQIA+, for instance. Several 2022 Youth Partnership studies on the impact of Covid-19 on young people and the youth sector in South-East Europe as well as in Eastern Europe and South Caucasus reflect these tensions.

Yet, the Youth Partnership study on young people’s right to assemble peacefully shows organisations are not passive when faced with barriers to the right to assemble, including restrictions to their functioning. Their responses range from resistance in adversity, to adaptation and compliance with the interests of dominant illiberal powers. The report pointed to mission drift: a survival strategy for some organisations, yet, a major risk for the civic sector, often trading advocacy and watchdog activities for service provision (Deželan 2022).

Are there any ways out? The removal of legal, administrative and practical obstacles to the right to assemble requires approaches that are highly complex. Isolated examples of “good practice” may be both insufficiently structural (when carried out by a single organisation or through a single legislative measure) and weakly transferable. Instead, actions that are well planned and strategic, long-term, based on a collective commitment of strong coalitions with diverse actors and on a larger range of tools, seem more promising. The report also called for shifting the narrative from needs, to the language of rights, to reminding states of the social contract.

Youth transitions – growing up is harder now

Youth transitions – growing up is harder now

The Youth Partnership’s symposium “Navigating Transitions: adapting policies to young people’s changing realities” was organised in Tirana, the European Youth Capital 2022. It gathered over 100 participants to reflect on “what paradigm shift is needed in youth research, youth policy and youth work to support young people’s aspirations” (EU-Council of Europe Youth Partnership 2022). The discussions opened less charted territories. Participants asked, for instance, whether destinations remained the same and whether – given the changed circumstances – we need the conventional benchmarks to adulthood at all. Who defines youth transitions and for whom? Based on whose criteria? Whose perspectives are gaining policy traction, and which are losing legitimacy? How do gender, ethnicity and location play a role in (re)defining youth transitions? These questions, launched by Ilaria Pitti and Howard Williamson during the symposium, attracted insightful debates. Here are some takeaways to reflect upon. I’d like to pre-emptively apologise for potentially taking you out of your comfort zone.

To start with: Youth transitions to what? “Transition to adulthood” frames young people as a group undergoing a developmental process, and adulthood as a stage of accomplishment, which may be seen as “adultocratic”. After all, we rarely speak about adults’ transition to old age. “Transition to autonomy” sounds better. Being able to think and make choices independently are valuable aspirations. But they are not without cultural biases, as “autonomy” underplays alternative relational models such as interdependence, mutuality, connection and care. Eventually, one may link autonomy with male, middle-class and Western conceptualisations that frame competitive and less sustainable social environments. The Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated the extent to which young people see themselves in relational terms: while providing support in their communities and experiencing mental distress when socially isolated. If autonomy is a goal, how can one explain the emerging trends in co-working spaces among young people, who are searching to escape the isolation of the “work from home” model as discussed at length in Papageorgiou 2021? Nevertheless, one can build an argument that autonomy is not synonymous with egocentrism, that it allows for bonds. On the other hand, dependency is not a sensible purpose, either.

What about the grand narratives: transition to work, independent living and parenthood? Increasingly, the structural conditions are such that standard transitions are not tenable. Work is increasingly precarious. This means lower income and social protection, but also a deeper sense of instability, fractured social bonds and poor occupational identities. The transition to independent living is difficult and unfair to the young generations because of decreases in income relative to the cost of living and housing and a concentration of wealth among older generations. Besides, European and national policies have focused so far on employment and training, without taking into account the importance of dignified and affordable housing as a prerequisite for independence (see the 2021 report: Serme-Morin 2021). As for transitions to parenthood, it has been argued that young people delay or forgo having children: for economic and cultural reasons, among others. The prospects are not better, as shown in a 2022 report on young people’s financial capability: they undergo a general level of economic stress and must also prepare for risks and tolerate insecurity.

Overall, it has long been noticed that “growing up is harder to do” (Furstenberg et al. 2004) and that traditional benchmarks (marriage, parenthood, independent living, employment) are no longer perceived as prerequisites for an adult identity, but as personal preferences and choices. According to Ilaria Pitti, young people came to (re)conceptualise transitions in relation to other models of relationships and non-hierarchical networks of communal living or professional collaboration. By asking young people what transitions mean to them, the chances are that new constellations of “markers” of adulthood are likely to emerge, as Ilaria has argued. We may commend such alternative stances, as (yet isolated and experimental) moves towards more sustainable and fairer societies that oppose a culture of privilege, competition, inequality and disregard for the environment. Or we may see them as the best solutions at hand to handle uncertainties, including the impossibility to reach previously attainable goals, as is the case of the young people interviewed in a recent Horizon 2020 project (Unt et al. 2023).

Yet, the celebration of youth agency in adversity may send a convenient policy message (young people make it, despite the odds, including by redefining transitions). This should not exempt policy makers from ensuring that enablers for the conventional transitions are present. After all, many young people still have fast-track transitions from school to work, to family formation or to unemployment.

Covid-19 and transitions – what have we learned?

Covid-19 and transitions – what have we learned?

In addition, the pandemic brought to light previously tacit transitions that were not on the conventional policy radar, such as health transitions. As the work of the Youth Partnership shows, the newer cohorts have poorer health outcomes than previous ones. Several previous concerns related to the health implications of environmental pollution, poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, tobacco and alcohol use remain insufficiently explored. The mental health implications of the pandemic are still not completely understood, as illustrated by the work of the Knowledge HUB: COVID-19 impact on the youth sector.

To add to this complexity, we may also observe that the youth sector itself is undergoing its own transitions. It has moved from offline to online and then to hybrid activities, from unstable to even higher staff and volunteer turnover as highlighted in a 2022 report, or from standing up for human rights and the rule of law, to service provision to reach well-being or employability goals.

Ultimately, the term “transitions” also conveys a certain notion of fluidity and linearity. But it is increasingly evident that young people’s transitions may be fractured, interrupted or reversed. Youth Knowledge Book #27 also highlights the critical importance of sustained support to disadvantaged groups, in particular in challenging times (ex. young Roma, young people with learning difficulties or with physical disabilities and mental disorders). Howard Williamson’s presentation of a 2023 book (Krzaklewska et al. 2023), brings to the fore alternative concepts: “waithood”, “stuck”, “life on hold”, among others.

Youth Knowledge Book #27 explores how digitalisation shapes youth transitions and how the use of technology (including artificial intelligence) can inadvertently sustain discrimination (Moxon et al. 2021). The volume goes beyond issues of access and digital divide by unpacking the upper middle-class, male and Western biases that are inbuilt in the technologies. The publication is valuable for contributing to the heated debates on how technology is part of exclusion and political suppression, how it can inadvertently sustain discrimination and why a more democratic approach to the control of tech giants is good for young people and our societies. Additional research on youth workers’ perspectives on digitalisation, technology and artificial intelligence, and how young people are involved in the efforts to regulate it, support the youth sector to start important conversations on these issues.

In conclusion, this multi-coloured picture of activities and resources shows that while previous crises were mainly about “fixing economic problems”, the responses needed now are far more complex. The Youth Partnership expanded the conventional registry of resources and responded to the calls from the youth sector to develop a knowledge base to support policy engagement beyond employment and education. While the process is not about finding definite solutions, it does meet an important function of opening up debates on new topics.

References

References

Deželan T. (2022), “Covid-19 impact on youth participation and youth spaces: research report”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/72351197/The+impact+of+the+covid-19+pandemic+on+youth+spaces.pdf/9bfe2c91-6cc1-2fdf-4d3f-7197b350fd7d, accessed 7 December 2023.

Deželan T. et al. (2020), “Safeguarding civic space for young people in Europe”, European Youth Forum, available at https://tools.youthforum.org/policy-library/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SAFEGUARDING-CIVIC-SPACE-FOR-YOUNG-PEOPLE-IN-EUROPE-2020_v4.0-1.pdf, accessed 7 December 2023.

EU-Council of Europe Partnership (2022), “Navigating Transitions: adapting policy to young people’s changing realities”, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/symposium-2022, accessed 7 December 2023.

Furstenberg F. F. et al. (2004) “Growing up is harder to do”, Contexts Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 33-41.

Krzaklewska E. et al. (2023), Youth transitions through the Covid-19 pandemic, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

Moxon D. et al. (2021), Young people, social inclusion and digitalisation: emerging knowledge for practice and policy, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

Pantea M. C. (2021) “Young people’s right to assemble peacefully. A mapping study, in preparation of the first review of the recommendation CM/Rec(2016)7”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/47261815/Review+of+literature_Art+I.2_Pantea_final.pages.pdf/12a1929c-b031-22f2-bfc8-2b344154cdb0, accessed 7 December 2023.

Pantea M. C. (2022), Navigating transitions: adapting policy to young people’s changing realities, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/116339195/Navigating+Transitions_Report_WEB.pdf/b52375a6-b218-69ac-608e-dc740a079b69?t=1677493850696, accessed 7 December 2023

Papageorgiou A. (2022), “Emerging trends in coworking spaces among young people”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/64941298/POY-3-co-working.pdf/c933134a-2bc8-65e9-69a6-9d57e432bc58?t=1637751180000, accessed 7 December 2023.

Pitti I. (2022), Understanding, problematizing and rethinking youth transitions to adulthood, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/116339195/Symp_Analytical+Paper+-Transitions+to+Adulthood.pdf/df42d656-d110-4c44-fe5f-c7e0c1336d4e, accessed 7 December 2023.

Potočnik D. (2021), “Review of the documents on young people’s access to rights and non-discrimination: a desk research study”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/47261689/2021-Review-documents_access-to-rights_discrimination.pdf/b1d46a06-7707-3230-954e-97f62ac45475?t=1619175192000, accessed 7 December 2023.

Potočnik D. and Ivanian R. (2022), “Youth services during the Covid-19 pandemic – a patchy net in need of investment”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/72351197/Access+to+youth+services+during+Covid-19.pdf/f8c8274e-475f-c50d-fe01-e51d07ba6fa5, accessed 7 December 2023.

Serme-Morin C. (2021), “Access to independence and housing exclusion: why we shouldn’t leave young people on the front line of Europe’s dysfunctional housing markets”, Youth Partnership, available at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/64941298/POY+4+-+Young+people%27s+housing.pdf/479215de-f558-33fe-5dad-d5eda7607d31?t=1636555211000, accessed 7 December 2023.

Unt M. et al. (2023) Social exclusion of youth in Europe: the multifaceted consequences of labour market insecurity, Policy Press, Bristol.

Maria-Carmen is a professor in sociology in Romania and a Member of Pool of European Youth Researchers Advisory Group.