Rural youth adapting to challenges presented by Covid-19

by Russ Carrington

08/102020

The impacts of Covid-19 are widespread and generally well documented, but how are young people from rural areas affected? This article explores their mental well-being during the pandemic and optimism for the future, which in turn poses some considerations for all of society.

Across the EU-27, 22.3% of the population live in predominantly rural areas, and in the United Kingdom this same statistic is as low as 2.9%.1 Throughout the world the ratio of rural to urban populations has been gradually decreasing and with it the proportion of young people living in rural areas – who have been increasingly drawn to the “bright lights” of the cities.

But what does this mean for the rural youth who call the countryside home and how have they been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic?

A project in Scotland has been looking into this as part of its wider international work to develop leadership skills, create positive change and empower young people in the countryside. The Rural Youth Project was founded in 2018 in response to the increasing need for young people to play an integral part in making rural places attractive and viable for rural youth to build their lives and their futures there. It has hosted a number of ideas festivals, vlogs and online workshops, and importantly conducted surveys to provide insight into the challenges faced by rural youth.

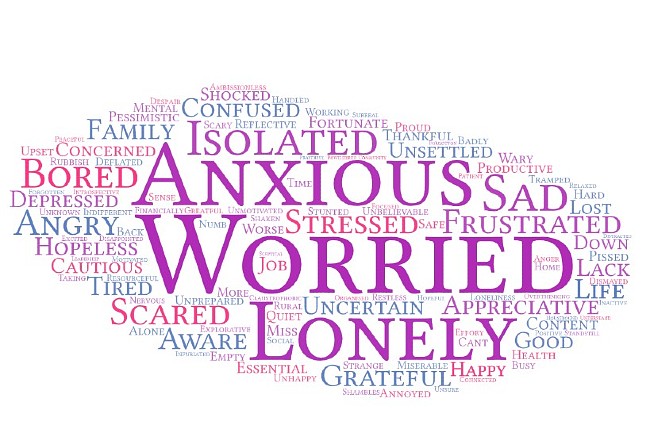

In its most recent online survey of over 600 18-28-year-olds, respondents described how they felt during the Covid-19 lockdown using up to three words, and mostly cited negative feelings of anxiety, worry, isolation and loneliness.

Mental health charities have had to step up to support people’s well-being across society during Covid-19: The Farming Community Network, a charity specifically working in rural areas, has stated that 71% of new calls to its helpline since lockdown began have been stress-related.2 To combat this upturn many charities have been working together on campaigns, compiling useful information to help people in need and creating engaging video content on social media to help encourage conversations about mental health.

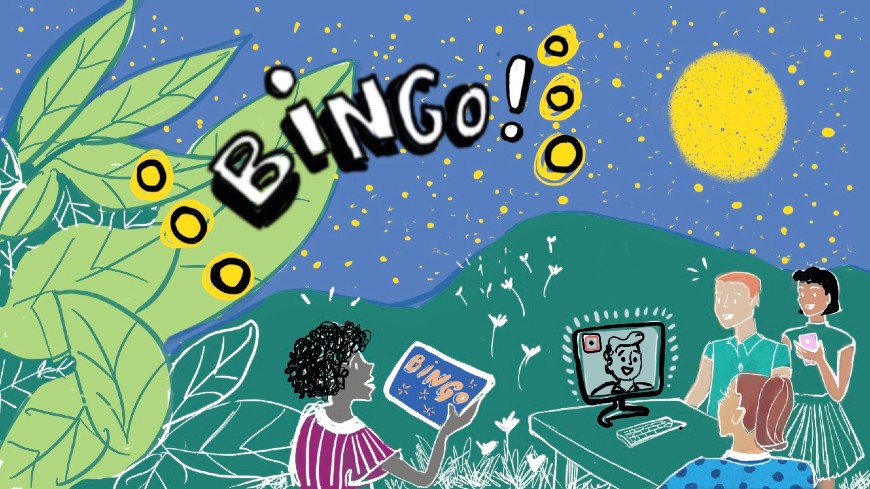

Organisations that work with rural youth have also quickly responded where they can. Rural Youth Europe is an international NGO which normally hosts a variety of European-wide events to facilitate intercultural exchange, learning opportunities and leadership development. It is entirely youth-led and stands as an umbrella organisation for rural youth movements in 21 different countries and represent

Birgit Kuslap, aged 24 from Estonia, sits on the board of Rural Youth Europe representing rural youth organisations from eastern Europe and describes how the NGO has quickly had to adapt:

Young people are missing the social interactions that they would normally get from our summer events, so we’re doing everything we can to keep some positive vibes and help continue some cultural exchange over the internet. We created an Instagram Bingo which participants from former events could take part in and have friendly competition with their friends across borders and relive positive memories. We’ve also been encouraging our followers to post upbeat pictures on social media of some of their favourite Rural Youth Europe moments.

Wehosted a virtual exchange with all member organisations to share best practice in dealing with the crisis and adjusting to new ways of working. There have been some really good ideas coming forward. The possibilities of online learning and educating have been really eye-opening.

In eastern Europe lockdown was not as strict as we heard from the news about other countries and whilst for me personally I was able to walk and exercise in the countryside, I did not see many people on the streets or from the balconies so it was still quiet and felt isolating. However, we have seen that people, especially young families and school children, have been escaping out of the cities to the countryside and to grandparents. It already seems that in Estonia at least, living in rural areas is getting more popular, including for young people.

Connectivity

Connectivity

Ninety four per cent of young people believe digital connectivity is essential for their future in rural places, yet currently slow speeds and poor mobile phone coverage deleteriously impact their lives.4 These limitations create practical implications, such as a route to market for micro-businesses or participation in online learning (which require good bandwidth); as well as social implications linked to social isolation which has been compounded by Covid-19.

Close to 60% of rural youth also stated that the quality of their broadband has been negatively impacted during lockdown,5 which is presumed to be the result of many people working from home more and putting a strain on digital infrastructure.

However, rural youth are changing their outlook as a result of the pandemic…

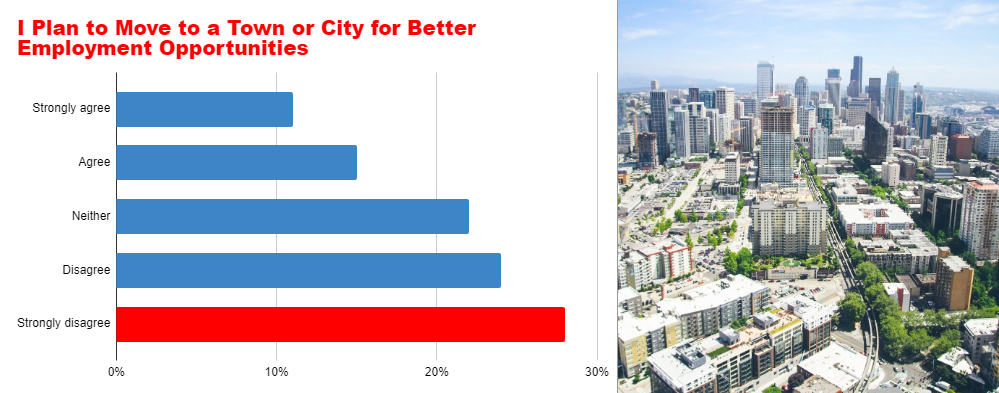

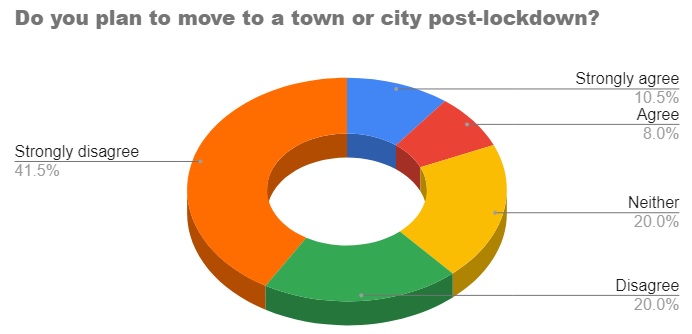

In the project’s 2018 survey, those surveyed were asked about whether they plan to move away to a town or city to seek better employment opportunities. The responses showed that twice as many respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement (52%) than agreed or strongly agreed (26%).

When asked a similar follow up question in the recent Covid-19 survey, over 60% of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the question “Do you plan to move to a town or city post-lockdown?” and only 18% stated they agree or strongly agree with the statement – a notable shift.

Whilst some respondents still agreed or strongly agreed that they might relocate, the majority cited they would be doing so temporarily for further education or university rather than for long-term employment opportunities. This might indicate that they feel safer and more secure in the rural areas they know and call home.

But why do young people want to live in the countryside in the first place?

The majority (80%) of the 2018 Rural Youth Project Survey respondents identified an emotional relationship with family or their partner as the main reason for living in a rural area. Comments such as “I grew up here”, “I work on the family farm”, “My friends live here”, were common.

This yearning for stability and familiarity is widespread throughout many of the comments made on the Rural Youth Project Survey and during events, and the project’s vloggers consistently bring up family ties and “shared history” as a reason for living where they do.

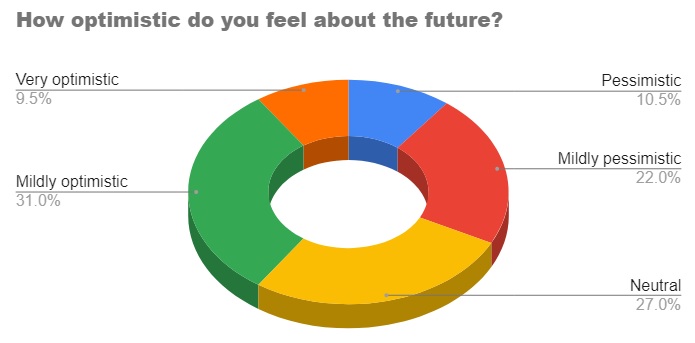

Covid-19 has, however, had an impact on young people’s optimism for their future with only 40% of young people feeling mildly or very optimistic in the Rural Youth Project’s most recent survey, compared to 72% of young people in the 2018 survey. Whilst other data suggests they want to stay in rural areas, this does indicate that they feel more uncertainty on the horizon than two years ago, which itself can drive up anxiety if not addressed.

Post Covid-19

Post Covid-19

There is widespread consensus amongst rural youth that society won’t be going back to normal when Covid-19 is over. They acknowledge that we’ll be entering a “new normal” and draw parallels from their grandparents’ experiences following the Second World War where a time of crisis had led to rapid development of technology and new social norms.

Being under lockdown has meant that no passengers can travel to and from the mainland by ferry, and only essential deliveries are able to get through. Whilst this has caused some difficulty it has actually strengthened our island community.

Feeling a sense of community has been redefined since the rise of online social networks but Amy reflects that

Ironically I’ve for once felt less isolated than many of my friends in the big cities. I think now that all of society has a shared understanding of what isolation means and feels like, people will better appreciate the importance of community.

Social media and information technology have certainly had a positive role to play for young people and provided access to newly created initiatives that have helped everyone stay connected, socialise, continue learning and even keep fit.

I’ve never felt the opportunity to connect to different activities going on and to meet new people outside of my usual circle compared to before Covid-19, But poor internet connectivity and variable phone signal is a limitation in rural areas like ours. We’ve learnt to be patient though. Island life makes us resourceful, sometimes in practical ways, but also socially and professionally. I think this approach is applicable to all rural areas and helps us to be emotionally resilient in times of change.

Despite Covid-19, many young people across Europe also remain concerned for the future of the planet and for climate change, spearheaded by young activists such as Greta Thunberg from Sweden. But they are also smart enough and brave enough to see that change is going to be a regular part of their lives and that perhaps the global pandemic is the catalyst for adaptation and resourcefulness.

One interesting example where this is already taking place as a result of Covid-19 is that many people are growing more of their own vegetables so that they can eat local, be more resilient and less dependent on global supply chains. This is prompting young people to learn new growing skills from their grandparents and exchange knowledge with their urban and rural peers alike via online platforms, and even swap seeds and produce.

Growing plants and being with nature is proven to improve mental health6 so this is just one adaptation activity where concerns, anxieties and even boredom can be addressed. The key to bringing these solutions to fruition is simply to talk and communicate, to reach out to friends, strengthen our communities, share our feelings, and remember it is okay not to be okay.

Rhiannon Andrews from Wales has turned to growing her own vegetables as a way of connecting with her peers from the farming community and to help feel more grounded during these uncertain times. She says she has gained great fulfillment through nurturing and seeing her food grow. It has provided her with a safe haven and improved her mental wellbeing

3. www.ruralyoutheurope.com/about.

4. www.youthlinkscotland.org/media/2803/ryp-report-2018-lr.pdf.

5. Rural Youth Project Covid-19 survey 2020