Decolonising youth work

by Nafula Wafula

02/12/2019

I speak from my lived experience as a young person whose life has been defined by the challenges that affect the world today, with the awareness that my challenges mirror those of countless others thousands of miles away from my home.

Enter! Youth Week. An amazing forum that brought together young people and youth workers across Europe to engage on pertinent issues affecting their lives and work, specifically, social rights. I had the honour of being a participant in this year’s conference and the insights shared were both practical and inspiring. You may be wondering why a young Africa-based woman participated in a forum that focused primarily on issues affecting young people in Europe. Well, I was there in my capacity as the vice chairperson for policy and advocacy at the Commonwealth Youth Council. The Commonwealth is a political association of 53 member states, most of which were formerly colonised by the British Empire whose main role is to foster international co-operation and to advance economics, social development and human rights in member countries. More importantly though, I was there because we live in an increasingly globalised world where the issues affecting a young person in Estonia or Armenia, while differing in scale, are quite similar to those affecting those in my community in Nairobi, Kenya. My role there was not to speak for the young people from European Commonwealth countries, but to speak from my lived experience as a young person whose life has been defined by the challenges that affect the world today, with the awareness that my challenges mirror those of countless others thousands of miles away from my home.

The conversations I had with fellow peer youth workers, and young people at the conference informed my decision to write on this topic. The realisation that the work I have invested my life in is largely influenced by a past and history that is rarely acknowledged and addressed was unnerving to say the least. I found myself leaving with questions I had never quite considered before. Should youth work be viewed through a decolonising lens?

So what is youth work then?

So what is youth work then?

I had a conversation with my grandfather the other day. He told me about men and women in his village growing up whose sole purpose was the mentoring of young men and women. The next generation of leaders, warriors, parents. Mentorship and other forms of support were offered to young people, all shaped by rich culture and strong traditions passed down to generations. In Africa, similar to other countries of the world, youth work has an expanded tradition of volunteerism. Volunteerism has remained a strong feature of youth work within the local authorities and the not-for-profit sector today. In large sections of traditional African society though, the initial volunteer youth educators were grandparents who gave instructions on social and life skills to the youth (who usually spent a night in their grandparents’ huts) in the evenings before they slept.1 Does this not fit within the context of what we now define as youth work?

Youth work is defined by some as “all forms of rights-based youth engagement approaches that build personal awareness and support the social, political and economic empowerment of young people, delivered through non-formal learning through a matrix of care.”2

One could therefore posit multiple arguments as to whether this community-based youth education was actually youth work. One such argument may be whether the practice was rights based. By this I mean, youth work that is based on human rights frameworks and advances young people’s autonomy and agency. Essentially, support, mentorship and guidance were offered within the confines of power structures and dynamics – therefore erasing the concept of autonomy that is today viewed as being central to the practice of youth work. The assumption was that the elders held the interests of young people at heart, and guidance was aligned to the traditions of that particular community. Historically therefore, young people have been the focus of adult philanthropy; attempts to educate, manipulate, indoctrinate, subordinate, control, discipline, reform and liberate. At the same time, young people have been the target of adult concerns about their care, protection and welfare as defined by adults.3

Practice was also guided by informal codes of conduct, ways of living that were unwritten but strictly followed, traditions that bound together different generations and were for the good of the community. Belief systems anchored in African spiritualities and culture dictated what was deemed to be acceptable and what was not, and were used as remedies and solutions to delinquency and other vices that youth work as we know it today was built to address. The practices were meant to create social connectedness, emotional, social and ethical maturity, economic and social productivity, self-esteem and self-empowerment within caring and supportive environments, with the aim of creating productive members of their communities and continuing the legacies of their culture and traditions.

Colonisation and youth work

Colonisation and youth work

In the context of the Commonwealth for instance, cultural responses to youth work arose alongside postcolonial, usually state-supported practice. Before this, youth work, like most educational and institutional responses and frameworks in colonised environments, was shaped by colonial influences.4

While I was researching colonisation and youth work, I came across multiple essays on the colonisation of social work, development and aid, or rather the potential for colonisation to be further perpetuated through the aforementioned. Not much research has been done on the decolonisation of youth work. I did find some interesting schools of thought all pointing towards major areas that must be addressed if we are to chart the path towards decolonisation.5 I shall also refer back to my experiences as a youth work practitioner, and a young person from the global south. I have had the privilege of working within a grass-roots, national and international context as both a peer youth worker and a beneficiary of youth work.

Exporting youth work and knowledge

Exporting youth work and knowledge

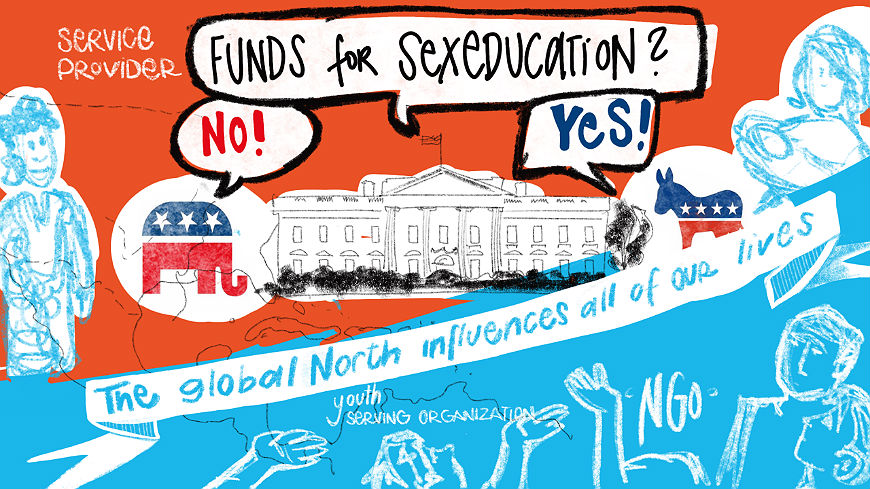

Youth work practice and knowledge have largely been exported from the “global north” to the “global south” and remain to be a practice with colonising potential. Youth work knowledge and practice as we know them today have largely been exported from Britain. The rights-based youth engagement approaches that are applied today, as well as the policies that have been developed, have borrowed strongly from youth work in Britain, at least within the context of Commonwealth states. The colonising impetus has continued through conduits such as the international education market and some international development initiatives. This includes the matrix that is used to define who falls within the youth bracket and the homogeneity this applies in creating youth development indexes by international development and aid agencies.

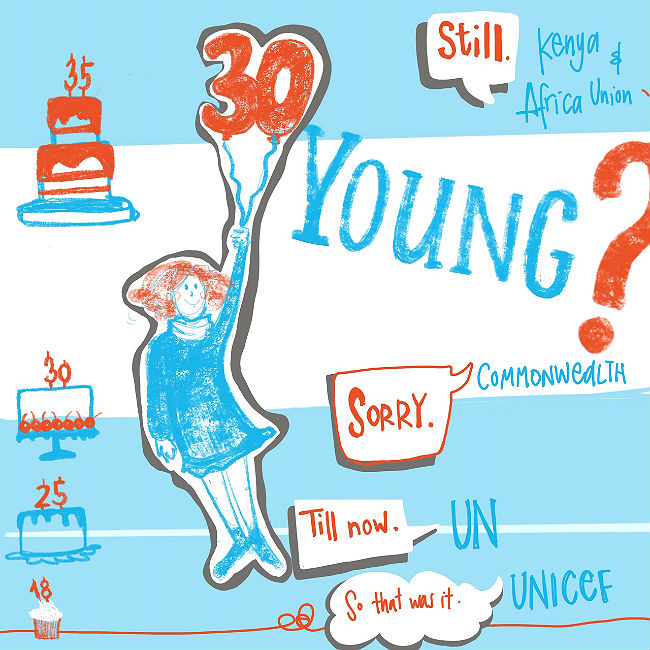

According to the UN, the World Bank and the Commonwealth’s definition, I am on my way out of the youth demographic. I cease to be defined as a young person the moment I hit 30. According to the prevailing policy framework in Kenya and the Africa Union though, youth spans the 18 to 35-year-old age group. The World Bank however posits that6 “Worldwide, it is not uncommon for youth to cover such a wide spectrum of the population.” However, they contend that “this is not practical as it spans 17 years and covers many stages in the lives of young people”. The UN definition often focuses on ages 15-24. Funding, programmes and research on youth by these institutions therefore often target the youth demographic as per their definition, despite this not capturing youth as understood and experienced in Africa and many other nations in the global south. As a result, a common/homogenous criteria is used to measure health, development, education, participation, etc. Most of the references drawn upon in many youth development indexes and reports consider research and knowledge drawn from the global north and apply them to the global south.

Transferring knowledge and practices across regions often results in contradictions when local conditions differ. This transference is sustained by the illusion that there is universality in knowledge. This theory of “northernness”7 is supported in works written on the production of social science knowledge in the global north. A good example is youth work as it pertains to provisions for sexual and reproductive health services, or psychosocial support when offered independent of/not considering a society’s culture and religion. A community relying on traditional seers and traditional forms of contraception will approach reproductive health service providers and counsellors with some level of distrust if such factors are not seriously considered in the design of programmes for young people within such set-ups. The perception that pre-existing traditions are retrogressive will affect the uptake of sometimes useful and impactful practices, and devalues the autonomy and social being of that community.

How funding policies affect youth work

How funding policies affect youth work

Resourcing and funding for youth services is also heavily influenced by policies and politics in the global north. Often, services that intersect with youth work such as sexual reproductive health and rights, as well as HIV programmes and services is determined by whether a sitting government in the global north is more conservative or liberal. A good example is the Mexico City Policy, popularly known as the Global Gag Rule: this is a United States government policy that blocks US federal funding for non-governmental organisations that provide abortion counselling or referrals, advocate to decriminalise abortion, or expand abortion services. It has had a large effect on the provision of services in programmes that are funded by them. The policy applies to foreign NGOs funded by USAID (an independent agency of the United States federal government). The policy affected foreign organisations offering sexual and reproductive health services by either forcing them to restructure their services to fit within its confines or lose a large percentage of the funding they are in dire need of. The simple fact is that a document has been signed in an office in Washington therefore putting into effect a policy that affects millions. Decisions are made behind closed doors, announced in front of flashing cameras, statements for and against the policy directives are made, and budget cuts are made. All the while, a young person’s life is being affected in a village, township or city elsewhere because the programmes and services that are to be delivered to him/her/them rely heavily on whether or not the government or organisation providing them is bank rolled.

Lastly, I should point to the exclusion and erasure of knowledge from the global south. Scholars from the global south are rarely cited and are notably absent in “metropolitan” texts. Their ideas are rarely introduced leading to their exclusion from what we understand as “world-scale”/global knowledge.8 This is also connected to the erasure of the experiences of communities from the global south which undeniably make up a majority of the global population. Empirical knowledge is informed by concerns arising in the global north at the exclusion of those arising in the global south, or periphery as Connell suggests. However, it is extremely shortsighted to assume that knowledge creation only occurs in the global north, and we suffer a huge loss by not acknowledging and tapping into the knowledge created in the global south. This global north-informed empirical knowledge is then used as a benchmark for empirical practice in the global south, therefore creating a perpetual cycle of assumptions of “if it worked here, it will work there”.

Remedies to the colonisation of youth work

Remedies to the colonisation of youth work

What then are some possible remedies to the colonisation of youth work? I shall share an example from an organisation based in Narok County, rural Kenya. In order to address the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in the Maasai community, Tasaru Ntomonok Initiative (a grass-roots organisation that works to eradicate FGM and early childhood marriage) conducts an alternative rights of passage (ARP) ceremony twice a year. The ceremony is conducted in August and December (also known as the “cutting season”), as this is the time of the year when schools are closed for the holidays and girls are most frequently circumcised. During the four days, the girls are taught Maasai morals, traditions and culture, as well as sexuality, health and general life skills. At the end of the programme, they are given certificates to confirm their “transition into womanhood”. They also teach the girls about the dangers of FGM, the importance of education, child rights, sexual abuse, substance abuse, self-esteem, good health, culture and harmful traditional practices. To mobilise the girls for the ARP, the so-called “godmothers” (who look after the girls during the programme), work with the organisation to spread the word via various schools, church and community networks. International organisations such as Africa Medical Research Foundation (AMREF) propagate such community-led approaches and, as a result, over 16 000 girls have gone through their ARP programme since 2009.9

"Voices from the Community as they embrace the Alternative Rite of Passage in place of FGM"

I believe it starts by accepting the fact that knowledge and practices are contextual and cannot be universalised. A deliberate consciousness of the history and culture informing the practices and knowledge in every context should inform how we create youth work practices and policies, as well as any underlying assumptions. This also applies to the generation of youth work knowledge by scholars. I argue with full acknowledgement that we live in a globalised and increasingly westernised world. However, the unique histories of each society means that every context is different and youth work practices and knowledge should manifest, and not ignore the resultant diversity, if only to add to the richness of the knowledge and practices. It is highly unethical to make presumptions about the transferability of core precepts and concepts inherent in youth work knowledge.10 We must acknowledge the consistencies and divergences in the practice of youth work between and across contexts. Therefore, funding agencies and international organisations should allocate more funding to grass-roots organisations whose core existence is more often than not informed by the lived realities and history of the communities they serve. Resources should also be dedicated to research and documentation of youth work practices from the global south. Programme design and practice should take into account the culture and context of their targeted communities.

It is also important to question what kinds of problems and issues are the foundation of youth work knowledge today and how they drive and shape practice today, more so as it relates to concepts and approaches such as “rights-based”, “community” and “individual”.

Decolonisation is a long and deliberate process, and one which youth work practitioners, funding agencies and those in academia must be willing to engage in. Youth work has core practice principles, but it needs to be continually emergent and adaptive because the young people it serves, and the social situation they find themselves in, are also continually changing and adapting.11 Youth work has to be shaped by local, cultural and social considerations in order for it to live up to its definition as a growth profession.

- “Youth work volunteerism in Africa: the case of volunteer business mentors for street youth in Kenya and Tanzania” by Alphonce C. L. Omolo (PhD), Director of Lensthru Consultants, Kisumu, Kenya. In: Commonwealth Secretariat (2017), Youth work in the Commonwealth: a growth profession, London

- Commonwealth Secretariat (2017), Youth work in the Commonwealth: a growth profession, London.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Edwards K. and Shaafee I. (2018), “work as a colonial export”, in Alldred P., Cullen F.,Edwards K. and Fusco D. (eds), The Sage handbook of youth work practice, SAGE.

- World Bank (2014), Youth in the Maldives: shaping a new future for young women and men through engagement and empowerment.

- Connell R. (2007), Southern theory: social science and the global dynamics of knowledge, Polity.

- Edwards and Shaafee (2018), “Youth work as a colonial export”, p. 60.

- www.equaltimes.org/in-kenya-alternative-rites-of?lang=en#.XcG6Z5r7TIV

- Edwards and Shaafee (2018), p. 70.

- Commonwealth Secretariat (2017), p. xiii.