Illustration by Daniela Nunes

Hope, sadness and the need for action

by Tomi Kiilakoski

In 2018, a new climate movement of young people emerged around Europe and the rest of the world. This movement combined novel and traditional ways of influencing, used social media cleverly and had a counter-cultural element that called for drastic changes in our way of life.

In Finland, the youth work community was struggling with meeting the demands of the movement, such as acknowledging the climate emergency and the urgent need to create a sustainable world.

The discussions about green youth work or sustainable youth work had only just started. The demands of the movement were not easily answered in the context of youth work, which was contemplating how it can be green or sustainable. There were burning and difficult questions: how has youth work promoted learning about sustainability? Was there enough awareness about the importance of ecological themes? Given that most of the youth clubs were built before 2000, they are not energy efficient. How can youth work show that it takes sustainability seriously?

Hence, in 2021, in order to explore and understand how young people in Finland felt about ecological issues, the annual youth barometer survey was conducted on the topics of sustainability and the environment. The Youth Barometer is a survey measuring the values and attitudes of young people aged 15 to 29 living in Finland. It has been carried out annually since 1994. Yet, this was the first time ever that it dealt with ecological themes, which illustrates that at least in Finland environmental policy and youth policy had been seen as two separate fields. With the emergence of the climate movement – such as climate strikes, demonstrations and taking part in the discussion with policy makers – it has become clear that environment and sustainability are an integral if not core business of youth policy.

The results give a lot of food for thought for youth work. Four distinct themes emerged as urgent for youth work in Finland, and I believe, elsewhere.

Is there a disagreement on sustainability?

Is there a disagreement on sustainability?

The environmental crisis has a definite generational character. Adapting to and reducing the effects of climate change will be tackled by the new generation well after my generation has faded away. To put it bluntly, humankind has had quite a feast. The current generations have eaten well, have drunk in abundance and as a result have left a pile of dirty dishes on the table with a note saying: “Please clean up. Pay the bill. We were too busy and too lazy to bother.”

The results show that young people in Finland see the environment as a top priority.

- A clear majority of young Finns (9 out of 10) agreed that climate change is a fact, caused by human actions.

- The share of denialists was only a few per cent.

- Over three quarters of young people disagreed with the statement that it is not reasonable to act if the others are not doing so.

The consensus on environmental issues manifested itself in the deeper issues as well. The questions dealing with the ethical attitude towards sustainability showed a strong commitment to protecting nature and preserving the natural heritage, with 86% strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statement that “the inherent value of nature must be taken into account in decision making”. While 75% of young people agreed that the measurement of our enlightenment is the world we leave behind.

Most of the young people, regardless of their political background, felt that environmental issues are important and they have to be dealt with in a fair way. For youth work this poses the following question: what type of world will current youth work leave behind? As a community of practice, do we have a shared understanding about sustainable youth work?

How do I feel?

How do I feel?

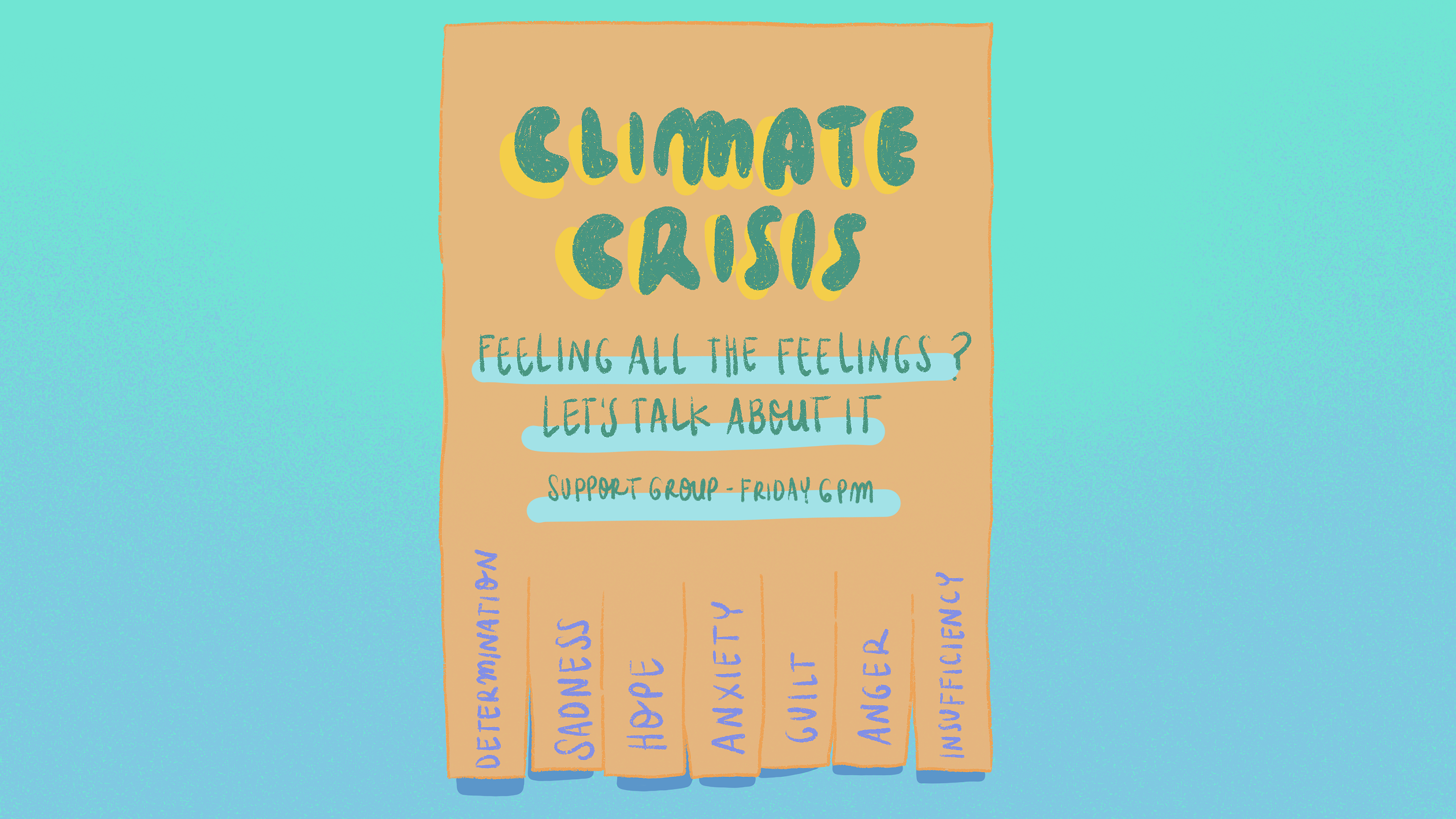

Young people react to environmental changes and looming eco-crises in different ways, and through different emotions. Emotions can also provide motivation to try to make a change. There are many climate emotions ranging from eco-despair to climate hope through guilt, anger, anxiety, joy and determination or an urge to act. Youth Barometer 2021 shows that young people experience a wide palette of climate emotions.

More than half of the respondents (59%) had discussed climate anxiety with others occasionally or frequently. Perhaps surprisingly, the most common climate emotions were the good feelings arising from sustainable choices, and sadness caused by the loss of biodiversity and the extinction of species. While 75% of respondents reported experiencing these emotions, 25% said that they experience feelings of insufficiency because of their environmental behaviour.

These results show that young people approach the environmental crisis in different ways, and we should not prepare ourselves for dealing with negative feelings alone. For me, one of the most important results of the barometer was a question about sadness. It is clear that we have to help young people to overcome anxiety and despair. But how should we react to sadness? Everyone is entitled to feel sad about the loss we see in our daily lives. The questions that nag me the most are: are we providing young people with spaces to discuss these feelings?; are we prepared to tackle these issues honestly with them?

On a positive note, a large share of young people say that they feel good if they act sustainably. Since youth work is good at inspiring action and is based on learning by doing, this means that there is a lot to be done if we can show to young people that it is possible to engage in environmentally friendly behaviour together with other young people. We also know from earlier research that acting together is a useful way of diminishing environmental anxiety (Kiilakoski and Piispa 2023: 217-18).

For youth work these results propose at least two challenges. Firstly, are there enough spaces where climate emotions can be shared and discussed in an inclusive manner? Secondly, is enough being done to show young people how to create a more sustainable life than the one they are currently living? In Finland it is more common to discuss what to buy for the youth club instead of thinking whether we should consume less and stop buying things even if they bring us brief happiness.

How do I know?

How do I know?

The respondents felt confident that they got proper information on environmental issues. Echoing one of the key elements of the new climate movement, namely respecting climate science, a clear majority of young people (87%) trusted science in environmental issues, and 72% agreed with the statement “I am well aware of climate issues”. This result is in line with the results of previous youth barometers which show that the majority of young people trust their abilities to understand key political issues in modern society.

Where do young people get information on environmental issues? As we know in the youth field, there are plenty of arenas of learning both in and outside formal education. Contrary to the expectations of some social commentators, social media was not the most important source of information for all young people living in Finland. The most important sources of environmental knowledge were traditional media outlets (television, radio, newspapers, magazines and films), with 78% of the respondents reporting that they had received a large or fairly large amount of information from these sources. Other important sources of knowledge were social media (74%), educational institutions (67%) and scientific publications (65%). However, for the youngest respondents aged between 15 and 19, social media was the most important source of knowledge.

In Finland, one of the most persistent youth policy goals has been securing at least one hobby for all the young, so that they can find something meaningful to do and enjoy the company of others. There has also been a hope that through hobbies young people will learn necessary skills to cope as citizens and as workers. Contrary to this optimistic attitude, the impact of these activities in providing information on the environment was marginal at best. Therefore, the challenge for youth work is to ask whether there are currently enough non-formal learning processes to help young people learn about the environment.

Some educational philosophers are saying that creating eco-social learning will become the main narrative of learning in the near future. This means that one should understand the interlinkedness of nature, economy and society and be able to look at things from a planetary perspective. If youth work does not succeed in taking part in this narrative it will not equip young people in coping with the world.

What should be done?

What should be done?

Young people agreed that environmental issues are of vital importance, and that we need to leave a better world for future generations. However, the more detailed questions we asked about how they acted in their personal life and in the public sphere, the more differences started to emerge. The same was true with questions on what Finnish society should do to help tackle the climate emergency.

- The majority of young people have not given up on things that damage the climate and which are important to them. Out of the respondents, only 39% reported having given up something important to them for environmental reasons.

- It has been reported in a lot of studies (e.g. Christensen and Knezek 2015: 776; Tranter 2011: 92) that there are clear gender differences in environmental behaviour. In accordance with this, women had given up something that was important to them more often than men. The respondents were asked in more detail about eight environmentally friendly consumption decisions. These included recycling rubbish, diminishing energy consumption, diminishing the daily amount of water consumed, adopting sustainable eating habits, repairing a product instead of buying a new one, buying a pre-owned product, avoiding products which cause a lot of packaging waste and choosing a sustainable form of travelling. Young people under 18 had made more environmentally friendly choices. Also, those young people who considered themselves as leaning towards the left had made more changes in their behaviour.

- Collective action was far rarer than changes in personal behaviour. For example, 25% of respondents had taken part in group activities on the environment. One out of six young people had joined workshops or demonstrations.

Although one of the most visible activities of the new climate movement has been school strikes, not all young people think that they are an effective way to influence society. Acknowledging these differences helps the youth field to realise the tensions between the young. For example, those who considered themselves value liberal and/or leftist thought that strikes or demonstrations were an effective way to make an impact. Value conservationists and those leaning towards the right were more sceptical.

When designing the survey, we thought that it is important to ask young people about big environmental policy questions, such as who needs to pay for the damage caused, should the solution be guidance or “polluter pays” strategies and should the justice system take a harder stance towards the problem. These questions polarised the young in Finland. As perhaps was to be expected, young people leaning towards the right and to the left differed in their opinions.

For me, this points out that when discussing how an ecological transformation can be achieved, questions about ecological sustainability and social justice need to be tackled together. This unavoidably means that these political issues probably cannot be avoided. When deciding what needs to be done, some of the groups in society will probably pay a higher toll. When sustainable youth work is being developed, these political aspects most likely cannot be ignored. Training youth workers to find a fair yet ecologically sound way to deal with climate emergencies involves ecological, social and (youth cultural elements).

For me the most pressing questions since analysing these results has been as follows:

- If climate science requires us to act rapidly and systematically as societies, what will happen to those young people who are more sceptical towards environmental issues?

- How do we ensure that they feel included?

- What is the role of youth work in ensuring that all young people feel respected even if we are facing changes that are affecting young people unevenly?

Maintaining hope is the key

Maintaining hope is the key

The eco-crisis is a challenge that individuals and communities of practice cannot avoid. We are only starting to find a way towards green or sustainable youth work. In the process of doing so, we need to offer a vision of sustainability, understand how both negative and positive emotions move us, provide knowledge and discuss what to do. Of course, also the sustainability of youth work activities and facilities need to be questioned.

The results of the Finnish youth barometer show that the environment is a common concern for the majority of the young. It also shows that young people are asking for drastic changes. Yet it also shows that not all the young are willing to sacrifice activities that are important to them. Acknowledging the existing differences among young people will be needed. Then again, climate science tells us that we need to come up with rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society. This requires learning, and acting. Due to this, youth work can offer a lot, but it too needs to engage in a joint learning process.

We cannot shy away from facing the climate emotions of the young. At the same time we need to be able to create the conditions for hope. As the results of the barometer show, the young feel that actions are needed. There is no hope if we fail to act, and there cannot be action if we do not have hope. Perhaps the most challenging issue is how to discuss the fate of our shared world in a way that creates realistic hope, and find ways to show that we can be the change we need.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Christensen R. and Knezek G. (2015), “The climate change attitude survey: measuring middle school student beliefs and intentions to enact positive environmental change”, International Journal of Environmental & Science Education Vol 10, No. 5, pp. 773-88.

Kiilakoski T. and Piispa, M. (2023), “Facing the climate crisis, acting together: young climate activists on building a sustainable future”, in Reimer K. E. et al. (eds) Living well in a world worth living in for all (pp. 211-24), Springer, Singapore.

Tranter B. (2011), “Political divisions over climate change and environmental issues in Australia”, Environmental Politics Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 78-96.

Tomi has studied youth work for 20 years. At the moment he is trying to figure out how the greener youth work could be like.