Get outdoors, please!

Nature and adventure as a therapeutic tool in youth work

by Alexander Rose

07/12/2021

Don’t you think Covid has also brought some positive aspects to our lives?

In many ways, it has allowed us to stop and reconsider things that were running on automatic… Perhaps it has allowed us more awareness about what we do and how we act in life, and it has also helped us to value more our contact with nature during and after severe lockdown.

Nature and adventure have been present in youth work since the early days, and due to recent Covid events, perhaps it is also valuable to rethink not only how to use them, but also what they can be useful for. In this article, I would very much like you to consider that nature and experiential education, hand in hand, can be therapeutic; and by deepening your intervention with a few tools, they may be even more helpful in the current times.

Therapeutic youth work? Yes, and a “must” in current times. Aligned with Cooper (2018), I consider youth work in the frame of social pedagogy and, therefore, with an explicit therapeutic orientation. From this paradigm, we provide formal and informal counselling, and some interventions may be therapeutic. However, in youth work, we do not do therapy since it is a process, with therapeutic goals, provided by mental health professionals.

Before continuing, a bit of European history first. Back in 2015, I was honoured to join and co-lead for more than three years a group of devoted youth workers and therapists searching for the roots of Adventure Therapy in Europe. We were aiming to create a common understanding, and articulate a professional network of European practitioners, by means of the Erasmus+ Strategic Partnership Reaching Further.

We belong to nature

We belong to nature

The biophilia hypothesis, introduced by Edward Wilson through his book Biophilia (1984), brings up the idea that since our ancestors evolved in wild settings and relied on the environment for survival, we have an innate drive to connect with nature, to seek connections with nature and other forms of life (Capaldi et al. 2015).

Research has now demonstrated links between doses of nature and a remarkable number of health and well-being responses (Keniger et al. 2013). Just exposure to nature itself has important effects on our emotions, body and mind. This exposure to nature, “green or blue”, forests, parks or water, has been linked to improved attention, lower stress, better mood, and has even reduced the risk of psychiatric disorders (Capaldi et al. 2015). Being in nature, following the text of Repke et al. (2018), reduces significantly anger, fear, and stress and anxiety, and increases pleasant feelings. Exposure to nature not only makes you feel better emotionally, it contributes to your physical well-being, reducing blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tension, and the production of stress hormones.

Jimenez et al. (2021) list some of the most recent findings in this (not so new) field of interest and research:

Spending time in nature is linked to both cognitive benefits and improvements in mood, mental health and emotional well-being. Nature promotes cognitive development and promotes self-control behaviours. Experiments have found that being exposed to natural environments improves working memory, cognitive flexibility and attentional control (the capacity to choose what we pay attention to, and what we ignore).

Feeling connected to nature can produce similar benefits to well-being, regardless of how much time one spends outdoors. Some researchers have shared evidence that contact with nature is associated with increases in happiness, subjective well-being, positive affect, positive social interactions and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, as well as decreases in mental distress. Also, it might help to buffer the effects of loneliness or social isolation.

Both green and blue spaces (both forest and aquatic environments) produce well-being benefits. More remote and biodiverse spaces may be particularly helpful, although even urban parks and trees can lead to positive outcomes.

As a result, connecting with natural environments helps youngsters in current Covid situations to deal with anxiety and depression, promotes mindfulness and gratitude to accept better the life situation they are going through, and stimulates healthy physical activity and encourages social connection.

One step further and deeper into experiential learning: therapeutic youth work outdoors

One step further and deeper into experiential learning: therapeutic youth work outdoors

From a psychological point of view, adolescents and youngsters seek challenges and need to face difficulties in order to develop a healthy and competent new self (Papalia and Martorell 2015). Here, youth work is a helpful and powerful way to escort and guide in this natural process. There are many approaches and intervention paradigms, and the intention of this little article is to consider one “new” one: Adventure Therapy. This method has been explored enormously all over the world, and also, lately, in Europe.

Adventure Therapy’s most used definition is “the prescriptive use of adventure experiences provided by mental health professionals, often conducted in natural settings, that kinesthetically engage clients on cognitive, affective, and behavioral levels” (Gass, Gillis and Russell 2012). So, rappelling or surfing can be used intentionally to promote personal growth, and/or be used therapeutically. Activities we use in youth work, educationally, can be also used deliberately, with few changes, therapeutically.

Borders and bridges in between youth work and Adventure Therapy are clear sometimes only on paper. The biggest differences are that in Adventure Therapy mental health professionals seek depth of intervention, intentionally diving into emotional or behavioural problems with specific knowledge and skills. Another difference is that reflection and the process of transference is based on therapeutic goals, as in quitting or reducing smoking marihuana, setting life goals or establishing better communication at home. On the other hand, the main bridge between youth work and Adventure Therapy is the use of experiential facilitation processes and the overall attitude of the professionals towards the participants (Rose 2021). The professional’s attitude is included in the triangle of competencies of the therapist, being experience-qualification-and-personality. More concretely: he or she needs to be motivating, connecting, showing interest, supporting and being accessible to clients, having respect for diversity, an openness to change; and to being supportive, authentic, empathic, accepting, motivating and flexible, use active listening, and be useful for the participant (Vossen et al. 2007).

Vossen et al. (2007) define specific characteristics of Adventure Therapy, incorporating borders and bridges with youth work:

- Nature: one of the most critical aspects, and it could be experienced being conducted in nature and/or using nature components or metaphors.

- Experiential learning: regardless of the therapeutic approaches being used, experiential learning is always the basis and a part of the process.

- Adventure: the idea of perceived risk, physical, emotional, in the form of a challenge and/or a wilderness environment.

- A (guided) reflection process: it is what brings meaning to the learning.

- Meaningful relationship(s): it can be a relationship with the facilitator and/or with peers from the group.

These five elements listed above, therefore, can be included in three categories:

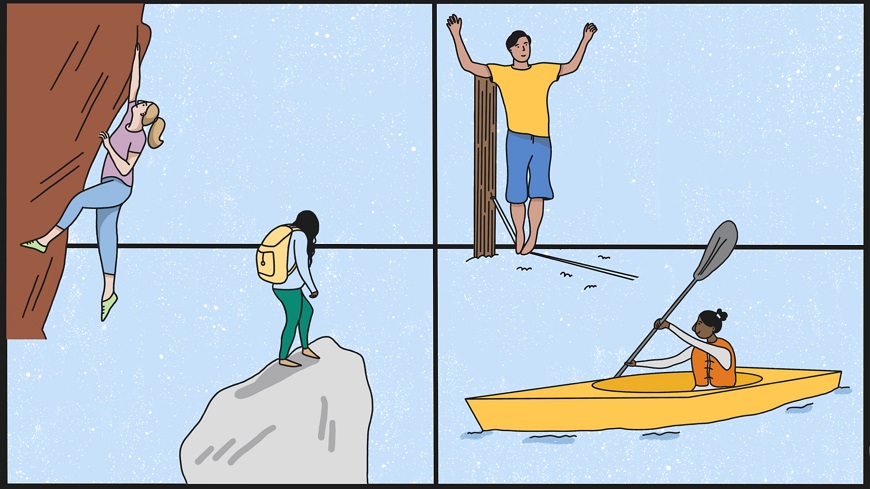

Nature and adventure activities: hiking, climbing, kayaking, slacklining, etc. can be used to expand the zone of comfort in an unknown environment, and create a playful and motivating context. To intentionally plan these activities is an invitation to action, and work towards problem-solving enhances and personal development. Here, you can help create different meanings through reflection and symbolism. A climbing route can become a metaphor for your life, and how you may struggle to reach your next hold alone. The learning, the insight, may be that you need to ask for help from your belayer in order to reach your next life goal.

Experiential learning: the main difference with youth work is that goals in Adventure Therapy are framed for a therapeutic intervention. Therefore, it is crucial in creating a safe context, both physical and emotional, to be able to get to a deeper reflection of the experience. Also, there has to be a clearer intention on transfer of the insights of learning to daily life, discovering the emotional mechanisms, and providing changes of cognitions and behaviours.

Therapy: as mentioned before, this intervention is developed according to individual and/or group aims. In order to work therapeutically, you need specific competences as a professional. Mental health professionals can be part of co-ordinated interdisciplinary teams in youth work. And also, some basic soft skills can be learned by youth workers in order to deepen the intervention, such as creating emotionally safe environments, learning active communication, understanding and learning emotional functioning and ways to change thoughts and patterns in participants, learning deeper reflective tools, etc.

Particularly, this method is suitable for youth at risk (Rakar-Szabo et al. 2017), and research has proven significant improvements in their self-efficacy, self-esteem, acquisition of internal locus of control and gaining of responsibility (Gass, Gillis and Russell 2012).

Conclusions

Conclusions

Adapting experiential learning with some components of the Adventure Therapy method, while providing outdoor experiences, may increase the general well-being of our participants. Therefore, I encourage you to bring groups into nature, and provide a safe environment for youngsters to grow and face their current difficulties through a healthy, reflective, adventure-based relationship.

Let’s bring our groups outdoors!

Resources

Resources

Adventure Therapy Europe: http://adventuretherapy.eu/

Nordic Outdoor Therapy Network: https://nordicoutdoortherapy.org/

German Adventure therapy (Erlebnistherapie) network, developed from the youth work context (Erlebnispädagogik): www.bundesverband-erlebnispaedagogik.de/fachbereiche/erlebnistherapie.html (in German)

References

References

Capaldi C. A. et al. (2015), “Flourishing in nature: a review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a wellbeing intervention”, International Journal of Wellbeing Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1-16.

Cooper T. (2018). “Defining youth work: exploring the boundaries, continuity and diversity of youth work practice”, The SAGE handbook of youth work practice, SAGE.

Gass M. A., Gillis H. L. and Russell K. C. (2020), Adventure therapy: theory, research, and practice (2nd edn), Routledge.

Harper N. and Dobud W. W. (2020), Outdoor therapies: an introduction to practices, possibilities, and critical perspectives, Routledge.

Jimenez M. P. et al. (2021), “Associations between nature exposure and health: a review of the evidence”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Vol. 18, No. 9, p. 4790.

Keniger L. E., Gaston K. J., Irvine K. N. and Fuller R. A. (2013), “What are the benefits of interacting with nature?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Vol. 10, pp. 913-35.

Papalia D. E. and Martorell G. (2015), Experience human development (14th edn), McGraw-Hill.

Rakar-Szabo N. et al. (2017), Adventure therapy with youth at risk. Focusing on key-elements of common understanding within the European Adventure Therapy Partnership project Reaching Further, http://adventuretherapy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ATE_Literature-Review-to-Findings-about-AT_2017.pdf.

Repke M. A. et al. (2018), “How does nature exposure make people healthier? Evidence for the role of impulsivity and expanded space perception”, PloS ONE Vol. 13, No. 8.

Rose A. (2021), Terapia a través de la Aventura, Cuando la montaña nos hizo grandes, Ediciones Desnivel.

Shanahan D. F. et al. (2015), “The health benefits of urban nature: how much do we need?”, BioScience Vol. 65, No. 5, May, pp. 476-85.

Vossen N. et al. (2017), “What is Adventure Therapy?” Findings of our partnership project, http://adventuretherapy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ATE_Findings-about-AT_2017.pdf