Illustration by Daniela Nunes

Youth work in times of (armed) conflict

by Nik Paddison and Snežana Bačlija Knoch

February 2022 saw the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. This war by Russia against Ukraine continues its relentless grip, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake. Communities are broken, lives lost and futures are uncertain. At the time of writing this article, the war has been going on for several months. In that time youth work has struggled, adapted, changed, evolved and even taken on roles outside of youth work. Amid this turmoil, youth workers are committed to serving young people, either within Ukraine or outside it as refugees. In the face of unparalleled challenges, youth work has undergone a remarkable transformation, adapting, evolving and taking on roles that extend far beyond its traditional boundaries.

Realistically, youth work cannot prevent war, and it probably cannot even be proved to prevent violence, but it can begin the process of re-socialising young people affected by conflict into seeing themselves as constructive agents of change in their societies and as active peace builders.

Lyamouri-Bajja et al. 2012: 37-38

When presented with the task of writing about youth work in times of (armed) conflict, the authors excitedly agreed and only afterwards reflected on the immensity of the challenge ahead! On one hand, youth work as a concept encompasses a great diversity of practices. When put in the context of an armed conflict, that diversity is further enriched with the uniqueness of each conflict environment. And on the other hand, even when somewhat defined, it is mostly visible in times of post-conflict confidence building and reconciliation. This does not mean that it does not exist in times of ongoing violence, but it is more difficult to capture and put into a specific shape or format, given that it becomes (even more) reactive, flexible and adaptable.

Both authors have had their fair share of experience of living and/or working in and/or working with young people coming from communities affected by war, conflict and violence and each of those brought in a high level of diversity (and complexity). Any (armed) conflict is without a doubt one of the most trying experiences that a person can live through.

A normal that is not normal

A normal that is not normal

When living and working in an active war zone the way of thinking becomes different, obviously influenced by what is happening in the moment. Everyday life continues in a normal and yet not normal way. Nik remembers his shock when talking with friends from Sarajevo in 1996. They explained to him that during the siege (1992-1996), children and young people regularly went to school or university and people went to work. A normal that was far from normal. During the daily mortars, bombs and snipers, people continued to live their lives.

A youth worker (Anton Serdiuchenko) from Ukraine recently wrote to us about his experience of being a youth worker in Ukraine at this time of war, and started his message with the following. “We have electricity and everything else without interruptions for one and a half months and it feels awesome. Sometimes we hear some jets or drones in the sky in my area, but everything is okay, I can say.”

The task of youth work is to normalise young people, to show them that it is normal to feel like that because it is an abnormal situation, to redirect young people according to their needs to the place where they can be helped, to activate them depending on where they must be actively engaged.

Pavlyk 2022. Quote from an interview

And so it is in Ukraine in this period. As Anton told us, “In my opinion, youth work didn’t even stop when the invasion began. It just a little changed its focus for some time.” “Youth work is active even despite rocket attacks, heavy battle fights and martial law.”

The focus on young people

The focus on young people

Trying to find the focus in all the diversity and complexity, the authors fell back to perhaps the most general of youth work definitions, which was found, quite conveniently, in the T-Kit 12: Youth transforming conflict: “the main objective of youth work is to provide opportunities for young people to shape their own futures.” (T-Kit 12, p. 20). And somehow this definition resonates just as well when applied to youth work in (armed) conflict.

In a survey “Research on the design of the Draft Occupational Standard ‘Specialist on Youth (Youth Worker)’ in Ukraine”, conducted by Nadiia Pavlyk (the research was conducted in the framework of the Council of Europe project Youth for Democracy in Ukraine: Phase II), there are two sets of statistics. The research was conducted in February 2022 at the beginning of the invasion, and again in August 2022. The report clearly shows the changes in priorities of youth workers. For example, in February ensuring youth participation was recognised but not strongly prioritised, in August the importance of youth participation had increased substantially. Areas such as the “self-fulfilment of young people” and “young people impacting the future” were not a priority at all in February but in August had become the other two top priorities for youth workers. As Nadiia points out, pre-war and in February, young people were “mostly treated as objects of activities” and as a result of the war, youth workers have become more aware of the importance of their work for the development and growth of young people to shape their own futures.

Youth work – the answer to everything

Youth work – the answer to everything

What is unique in a war context is that the future is blurrier and unshaped when faced with increasingly unsafe and uncertain times. This constant threat and uncertainty lead to youth work turning from being an ongoing process to acting as some sort of fire extinguisher.

Youth workers are expected to meet the needs and solve the problems of the young people in war-torn Ukraine without the knowledge, means or support to properly do so. This is not written as an attack on the quality of the youth workers or the authorities in Ukraine, it is written more as an observation of the situation youth work often finds itself in. We have seen it across Europe in various crises over the years: the unemployment crisis, financial crisis, Covid crisis, etc. In all these cases youth work is expected to step up with few resources and be a response to the crisis and to “fix” it. It seems that this expectation still applies in times of war.

The importance of youth work

The importance of youth work

Given that even in the best of times, youth work is one area of working with young people that shows the most flexibility and adaptability (often referred to as “Swiss army knife”), armed conflict is the time when these qualities are being put to the test on an almost daily basis, as both the circumstances and needs of young people can change in a heartbeat or with a single gunshot or a missile being fired. Therefore, (armed) conflict is a time for constant innovation of approaches, means and environments that try to “meet young people where they are” and support them in going through their days, while also offering them opportunities to not only survive the changing reality, but also influence and shape it as much as their well-being and confidence allows. And, maybe, just maybe, also reflect on these experiences in order to capitalise on the learning coming from it at some later stage.

In Pavlyk’s report, the youth workers she spoke to talked about the significance and importance of youth work during the war. They firmly believe that youth work must be there to continue to support young people in their development and towards their independence and it especially needs to be prioritising issues of trauma among young people. As one respondent noted, “Youth work remains applicable regardless of the war.”

At the beginning of the war youth organisations started gathering groups and chats for everyone who required psychological help or any other. At that moment I was a Young European Ambassador, and as a part of this initiative me and other Ambassadors shared information, wrote articles and communicated about how war is going and how it affects us and all Ukrainians.

Anton Serdiuchenko, youth worker

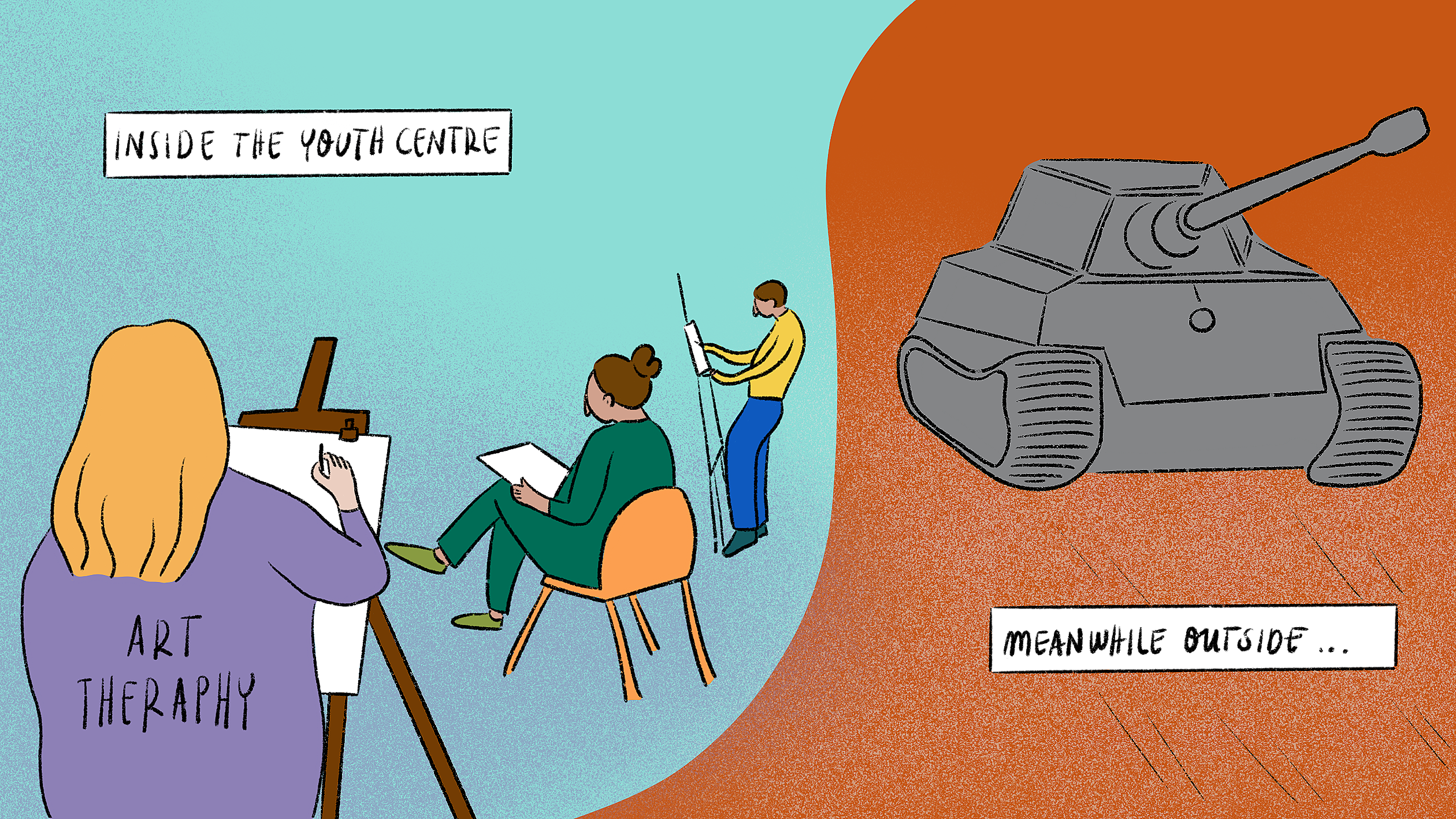

Youth work in Ukraine has changed; it has taken on more psychological support for young people, for example, some organisations have started art therapy. It is also supporting internally displaced young people to create organisations in their new places of residence while other displaced young people are joining existing organisations and strengthening them.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure

The breakdown of infrastructure in Ukraine adds to the problems youth workers are facing. Some things are common for the whole population, such as long periods of time without electricity and a lack of or complete absence of phone or internet. But it is also the physical impact – youth clubs, centres and offices have been destroyed, and some cities and locations are under occupation. Youth workers are constantly trying to find new spaces and many solutions are often temporary because the situation is constantly changing. This means that many youth workers are in a constant state of insecurity and have no continuity for themselves or their work.

Impact on young people

Impact on young people

Young people are often forgotten by societal institutions in times of armed conflict or even seen as a burden. On the other hand, however, as is the nature of war, young people become a valuable commodity. They are encouraged or drafted in to engage in humanitarian work, to volunteer on the home front and particularly to join the military.

The situation of young people in Ukraine is hugely impactful, both physically and psychologically. Many young people do not have access to education since schools are closed in some areas. There is high unemployment among the younger generations. Large numbers of young people are internally displaced or refugees. They need psychological support and are experiencing many mental health issues: trauma, anxiety, stress, depression, fear... One of the needs common to many young people is simply to be able to meet with their peers to share their feelings, and to support one another. Youth work and youth workers have a particular role in supporting young people’s physical and mental well-being, while providing assistance and protection, as well as essential information and guidance. On this level, youth work is there to serve the basic human needs of young people, because only when they are feeling safe and protected can young people engage in influencing their reality (and potentially their future).

Impact on the youth workers

Impact on the youth workers

The conflict is heavily impacting youth workers. The project report “Youth for Democracy in Ukraine: Phase II” by Olena Chernykh and Yuliya Ielfimova, shows that 60% of the youth workers in Ukraine are IDPs (internally displaced persons) and many others are refugees. The conducted survey shows that only out of 10 youth workers continue to provide youth work, 5 are partly providing youth work and 1 out of 10 has stopped working altogether.

According to the same report, the main challenge and need being expressed by youth workers in Ukraine is, unsurprisingly, for their personal safety and the safety of their families and loved ones. Many are experiencing a lack of psychological support which is leading to burnout. There are also personal and professional financial difficulties. The first from not receiving salaries and the latter due to little or no funding being available for daily youth work or projects – although this has changed according to more recent reports.

Lots of young people [and youth workers] have lost their income during the war. Even when they move to another city or region, they face the employment challenge. They do not know what to do and how to act. Yes, they can also volunteer, but they are interested in income to pay for accommodation, food and to maintain their families.

Pavlyk 2022. Quote from an interview

Additionally, the Council of Europe has actively supported youth work in Ukraine, and this assistance has been documented through a series of short videos within the project Youth for Democracy in Ukraine: Phase II. The primary objective of these videos is to gather and showcase youth work experiences. You can access these via the link.

Council of Europe youth work in Ukraine - Olena’s Story from Council of Europe on Vimeo.

The role of youth workers

The role of youth workers

Youth workers in many cases simply don’t know what to do; there is a lack of knowledge about how to work with young people who are in the middle of a war. They don’t know how to provide youth work, especially when there is bombing and shelling. There is little or no resource about good youth work practice in war time. Due to infrastructure limitations, there is a lack of connection among youth workers and it is difficult for them to communicate, whether that be to share good practice or offer support to one another. There is a strong desire to communicate, to exchange experiences, to formulate priorities, to develop approaches, activities and guidelines, and to co-operate and co-ordinate.

Youth workers are also being expected to take on a humanitarian role, something that many of them understand the need for but feel that it undermines their youth work practice. Youth workers are being asked to create activities to identify the humanitarian needs of a community and then provide or manage that aid or support. There is a demand for services that are not typical of youth centres, for instance providing basic medical training. The scale of the situation is so vast that many youth workers report being overwhelmed and demotivated.

The one thing youth workers do understand is the need to take on the role of support. Young people themselves can profit a lot from being able to engage in acts of support, empathy and solidarity that can only emerge in such trying times. As Ajša Hadžibegović writes in her article “Youth work in times of war”:

Contra-intuitively, it is in such extremely unfavourable conditions that the need for and potential for cooperation surfaces. It is then when we are realising we can’t do everything on our own, when we accept our limitations and vulnerabilities and when we also rely much more on each-others. That is a huge potential learning moment for youth workers and young people.

Hadžibegović 2022

A moment to reflect

A moment to reflect

As many of us who have gone through this experience can testify, conflict (even a violent one) is an incredibly potent learning opportunity about one’s own behaviours, attitudes, values, world views, etc. And while this learning might not occur in the middle of all the violence, youth work, with its opportunities for reflection can help in digesting and processing situations that can later on grow into significant learning milestones!

The future

The future

Perhaps the most significant development in that respect is working on young people’s prejudice and hate that almost inevitably emerges in situations of permanent injustice created by armed conflict. And while most of the work in this regard can only be done in post-conflict periods, the seeds of challenging prejudice are best planted while an armed conflict is ongoing, before fear transforms into deep-rooted anger and hate. What is more, youth work might be the only mechanism to prevent that, as some of the other relevant institutions might even fuel this hate further to serve different political agendas. Therefore, this task for youth work is essential, as from the authors’ experience in running conflict transformation and reconciliation programmes for young people in latent conflict or in post-conflict periods, when not already built on a solid ground, it is very easy for young people to slip back into hate that can take decades to deconstruct.

The youth workers

The youth workers

With all those essential roles that youth workers might need to play in times of violence, insecurity and injustice, the eternal question re-emerges: who is helping the helpers? From their own safety and well-being, through personal feelings of anger and hate, all the way to competence to deal with conflict around or even within a group of young people, youth workers are often left to deal with both their own and the burdens of young people on their own – without systemic help and support and expected to find their own ways forward. Therefore, it is essential that there is support provided for youth workers, be that in their own countries or in the international youth work community. As Ajša writes:

[...] youth work is not and cannot be a quick fix, and youth workers would benefit from support, learning opportunities and more resources, particularly in times of war in order to be able to more effectively support the young people.

Hadžibegović 2022

Youth Partnership resources

Youth Partnership resources

In light of the current war in Ukraine, the Youth Partnership launched some special episodes in the Under 30’ podcast series. These episodes are specifically dedicated to exploring the profound impact on young people and the youth sector in Ukraine, as well as showcasing acts of solidarity involving youth from both Ukraine and neighbouring countries. The podcast series’ objective is to provide a platform for representatives from the youth sector to share their insights, discuss the ramifications of the war on youth, and shed light on the various solidarity initiatives taking place.

References

References

Chernykh O. and Ielfimova Y. (2022), “Youth for Democracy in Ukraine: Phase II – draft report”, Council of Europe in co-operation with the Ministry of Youth and Sports of Ukraine and UNDP.

Council of Europe, Youth for Democracy in Ukraine, www.coe.int/en/web/kyiv/youth-for-democracy-in-ukraine.

Hadžibegović A. (2022), “Youth work in times of war”, FOCUS learning, FOCUS blog, https://focus-learning.eu/youth-work-times-war.

Lyamouri-Bajja N. et al. (2012), T-Kit 12: Youth transforming conflict, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

Pavlyk N. (2022), “Research on the design of the Draft Occupational Standard ‘Specialist on Youth (Youth Worker)’ in Ukraine in accordance with the standards and approaches of the Council of Europe in the youth field”, draft report, Council of Europe.