The seriousness of being funny

There are thousands of languages and dialects around the world, but we all laugh more or less in the same way. (Only when we write “laugh”, it looks a bit different in every language… but this is maybe for another Coyote article!)

by Simona Molari

07/12/2021

We laugh in every culture and language, and we all laugh in the same way; no one will ever ask, “What language is the other person laughing in?” We learn to smile even before we speak, around the tenth week of life, discovering its various functions bit by bit over the course of existence.

Culture and humour

Culture and humour

But there are more common elements between culture and humour such as gender roles, distance between people when talking, eye contact, body language, religion, which are all elements of cultures that need to be taken into account when we speak about humour. Think also about how some of these elements can become very dangerous: each of us in our lives has felt offended or touched in our sensitivity to a joke, a gag or a humorous expression, even if made with good intentions, but experienced in a painful way.

Only the fact that in dictionaries the meaning of humour changes according to the language makes me think that there are many aspects of culture which are playing a big role. If you check in different dictionaries, you will probably be surprised by the differences or similarities in the explanation of the same concept.

One very interesting book you can read on this by Rod A. Martin is The psychology of humor: an integrative approach, where he says that “Humor is a ubiquitous human activity that occurs in all types of social interaction”. Ah! By the way: humor or humour? Well, Mr Mark E. Taylor told me that those two words are the same, only one comes from the USA and the other from the UK! ☺

According to Gert Jan Hoefstade, researcher and teacher, in his great publication Humour across cultures: an appetizer,[1] he says: “humour will be partly universal, where it reflects human drivers; but in each society it will tend to concentrate on the issues that are most salient in that society’s culture”.

Humour, in fact, is influenced by each nation’s culture and history, traditions, way of being, society, norms, values, etc. And therefore, it is also evolving with it and changing over time.

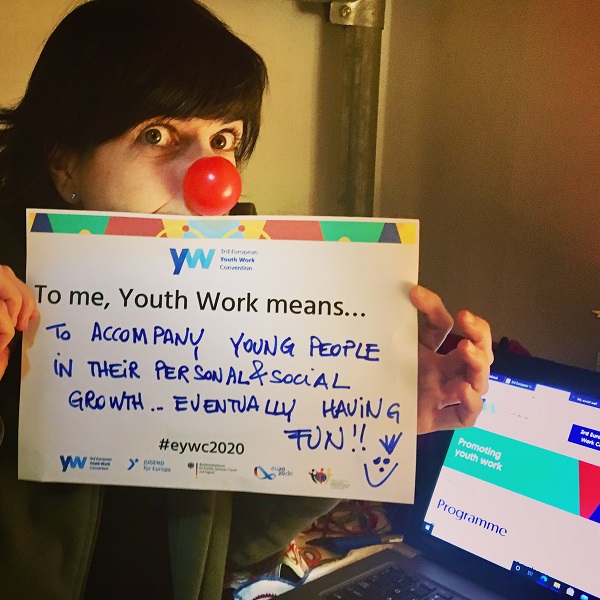

Another interesting cultural aspect is the red nose symbolising the clown, which I thought was universally understood. But it is not known everywhere.

One time I was at an international youth event and there was a participant coming from Nepal. I was telling him about me being a clown, playing in the street, and all my incredible stories about being a clown for 10 minutes, and at the end he said to me, “It sounds interesting… but what does it mean clown, and what is that?”

He had never seen a clown in his life.

In order to exist, humour needs the indispensable activation of connections made up of linguistic, social and cognitive elements: hence its complexity and the numbers of studies done!

Let’s take jokes: to make a joke or a gag in an international context can be “understood” in different ways, and often also misinterpreted, just simply because we are not aware of certain cultural backgrounds. I think that everyone has tried at least once to translate a joke and the results were absolutely different, even a disaster.

Mr Hoefstade in his book, mentioned above, gives a nice example of a famous person, let’s say the ex-USA president Ronald Reagan, who seems to have been a person with a good sense of humour, who went to Japan for a conference. He told a joke during his intervention and when the translator shared it among the audience, everyone was laughing incredibly. So, afterwards he asked the translator how she could have interpreted the sense of the joke so well, and she answered a bit embarrassed, “Sir, I did not translate the joke, I just told that you told a very funny joke”.

If you remember the iceberg model of culture, the “sense of humour” is well down under the water… and this is exactly what I am referring to. There isn’t a booklet that explains to you how to interact with other people in another culture in general; the same goes with that part of culture which is humour.

But maybe there is something like an international sense of humour? Well… given that culture is a big part of our sense of humour and what we laugh about, it is not only about differences, but we can also talk about common elements: think about the many subcultures from football followers to Star Wars fans, groups of friends or a group of participants at an international training course. Even after the few hours that we spend together building a group during an international activity or a youth exchange we have some common elements that we are laughing about.

But why is there so little about the use of humour in connection with youth work? Like my colleague Fergal Barr has already underlined in his blog,[3] I am wondering why, being such an essential element, that humour in youth work and in non-formal education has almost no reference at all. Even in the ETS[4] competence model on youth work it looks like this is not seen as an important competence at all.

Resource list

Maybe by now you are now wondering how your sense of humour is. Incredibly there are even tests that you can do to measure your sense of humour. An interesting one is called the Humor Typology Questionnaire (https://quiz.humorseriously.com/). It’s a bit like learning styles, isn’t it?

The questionnaire includes several categories: affiliative humour (used to reinforce membership of a group), self-affirming humour (based on self-exaltation), aggressive humour (focused on the other person) and self-defeating humour (focused on self-deprecation).

Anyway, understanding the nature of humour is also a subject of psychology, like you can find in this wonderful article which talks about the book What’s so funny? The science of why we laugh, in which psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers are trying to understand humour and explain the different theories (www.scientificamerican.com/article/whats-so-funny-the-science-of-why-we-laugh/). Even mathematics is exploring this and one very recent study is using quantum physics to understand how it works: www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2016.00053/full.

Here is an article with an interesting history and relationship between humour, laughing, learning and health, with an emphasis on the language of laughter: https://journals.physiology.org/doi/pdf/10.1152/advan.00030.2017.

Henri Bergson’s Laughter, 1900, was the first book by a notable philosopher on humour (the original title is Le Rire. Essai sur la signification du comique).

Also, the book of my maestro clown, Michel Dallaire: Le clown l’art la vie, 2015 (auto-edition, so not so easy to find without going directly – check the Facebook page: www.facebook.com/218993341548657/photos/a.1985787944869179/2593793227401978/).

The benefits of humour

The benefits of humour

Here, it is important to remind you why it is so essential that we laugh, as maybe not everybody knows that laughing is a well-being therapy itself. Laughter has physiological effects; it changes body chemistry and brain function, and is one key factor of health.

Laughter reduces stress, releases feel-good hormones, facilitates healing processes and even extends life. But above all, in everyday life, a good laugh makes relationships with people easier, is good for self-esteem, makes even complicated moments seem easier and is the most obvious sign of that positive thinking that makes life enjoyable.

Indeed, the health benefits of laughter have been demonstrated by numerous studies such as this: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S096522991830030X?via%3Dihub, just to mention one of them.

The benefits of humour and laughter are even referenced in the Bible, Book of Proverbs 17:22 (NIV), where it states: “A cheerful heart is good medicine, but a crushed spirit dries up the bones”, indicating that, even centuries ago, people understood that a joyful spirit has positive therapeutic effects, while the absence of joy may make you ill. But more recently, interest in the benefits of laughter therapy began to intensify in the 1960s. The first scientist to propose laughter as a field of study was Dr William F. Fry, a professor of psychology at Stanford University (California). He was also the first to do research in the field and to call himself a gelotologist (expert in the science of laughter). He published a series of studies on the physiological processes that are triggered during laughter, demonstrating that deep laughter is a physical exercise that strengthens the immune system, decreases the likelihood of respiratory tract infections, and causes the natural production of endorphins, true natural opiates.

So… in other words, laughter is one of the first factors of well-being – for all ages, and therefore in connection with the well-being of young people. Especially during the pandemic, where we had so much need to laugh and get back a bit of levity, it helped to lighten the atmosphere and “dedramatise” situations, which has crucial importance in group dynamics.

Fyodor Dostoevsky considered humour a useful tool to know and to know each other. In his book Crime and punishment, he said: “To know a man it is necessary to study not his silence nor his way of speaking or crying but what he laughs about”. This quote made me think a lot, and for me explains one of the reasons why it is important to use humour in our educational work.

Humour helps us to listen actively and to communicate without prejudice. In work groups humour creates a more cordial, informal atmosphere and a more relaxed, and at the same time, more profitable environment. It helps us to break down barriers and get to know each other in a genuine way, and to get closer. Being able to find the funny side of things in life and, primarily, of oneself (self-irony) fosters creativity and the search for alternative solutions despite difficulties. It can also offer people the opportunity to discuss painful personal events in a format that reduces distress and anxiety.

Myself as a clown

Myself as a clown

I am not a psychologist, nor a scientist. So why am I talking about humour and funny things? Maybe this is the right time to know a bit about me: how I became a clown and why a trainer and its connection with training.

But what is a clown, or better, what makes a clown a clown?

But what is a clown, or better, what makes a clown a clown?

It is about feelings, sharing, breathing, about somebody who generates emotions. Wow such a beautiful definition… Yes, a clown is about emotions, very true. They could be like someone who activates emotions. But it is not like having a TV remote control and saying: which emotion shall I activate now? You communicate, and activate some channels that maybe you will control, or maybe not.

The clown can be the activator of humour, just like the trainer. That’s why for me, humour is also a tool, just like a nuance of colour which supports learning. It can take different forms like sarcasm, black humour, absurdity, naïvity. It is up to us to understand when and which one to use, according to the situation and how we are and with whom we are interacting. It is like choosing the correct educational activity for a specific target group and objectives of the session.

In the courses that I followed on clowning, one other common element, a part of the emotions, was the work on ourselves. You need to look deep inside yourself and discover that something you consider a weakness can turn out to be a strength. What an incredible thing. And I guess this is also the key in all training. Only a trainer doesn’t have a red nose, well, not normally. Oh yes, the clown nose is the smallest mask in the world that you can put on and take off, because we are all vulnerable inside and a mask helps a lot. We are unsure, we have some intimate parts to play and when you are a trainer like me in front of people, you are worried about making mistakes. And so maybe you hide behind a role… but the clown doesn’t play any role, the clown is themself. We are generally worried about making mistakes. But this is the turning point, because the clown is playing with mistakes. You can take it and you can play, by being honest and turning your vulnerable moment into a strength. Because if you are a trainer in front of people, they see a person, and if you believe in what you do, others will also do the same. But if they see that you are not true to yourself, then it loses its value.

But a clown doesn’t need a nose to be funny and it is not enough to have a nose to be a clown (fortunately, otherwise the world would be full of clowns). The same goes with trainers! It is the same thing being a trainer and being funny or using humour.

I have met some different clown teachers in my life, but I consider only one to be my maestro: Michel Dallaire. Every time I told him that it was too difficult being a clown, he answered “What? It is the easiest thing in the world, you have fun, and people even pay you!” But for him, being a clown means generosity and being humble, as the clown always gives and says yes. That’s why the worst enemy is pride, because it means that you will not share all that you have to share.

It is not only a matter of language or jokes, but a matter of the whole “thing”. But this “whole thing”… what is that about?

What humour is not?

What humour is not?

Maybe let’s start by looking into what it is not! And a good way is to dismantle some false beliefs, and to look into some legends connected to this topic: the first one is the “serious business”. The idea that levity and humour undermine the mission of our work, that we can be seen as not taking what we do seriously, as if we’re joking around. This is, in my humble opinion, not true, but it is a risk. A sense of humour is motivating, is a way to reach others. It is a way to communicate, a language to reach people differently. Like storytelling, where you can use various colours (fantasy, dark, science or comic fiction), the same goes for humour being sarcastic, black or crazy. But it’s not that obvious and easy in fact, as it also needs an ability to understand situations, boundaries, feelings; it needs a dose of empathy and humanity. Therefore, the risk is being seen as simple, “not serious”, instead of as an intelligent motivator.

The second legend is that humour is about telling jokes! We need to remove from our minds the idea that humour and being funny is about telling jokes. It is not only about that. Jokes are part of it, and they can be very funny and good when done appropriately. Or very brutal and sharp, if there is a specific reason for that. But humour is much more than a joke: it can be a soft shade in what you say, or the use of words, images or actions, or through pictures, or a face that you make, a glance, a move of your hands, or just a pause in your talking or in your movements, or a breath, or just simply doing nothing. It can cause a smile or loud laughter. And the forms are lots of different ones, from the famous jokes, to innocent or biting sarcasm, to the physical gags, or stand-up comedy or much more. Remember that jokes can be hilarious, but also very dangerous: they can be a vehicle for prejudices and discrimination: just think about all the jokes about gender, countries, sex, religions… This really needs to be kept in mind, especially in intercultural contexts.

Another kind of legend is that if you are funny it’s because you are born like that. Or that certain cultures are funny such as: like me, an Italian. Some people have said to me “Of course you are funny! You are Italian, and you talk loudly and you move your hands like Roberto Benigni”. Well, believe me, I know many Italians who are absolutely not funny at all! But incredibly, a sense of humour is also something that we can work on!

Tips for working on humour

Tips for working on humour

How? Here are some tips: you can start by looking at the funny side of things, try to take something ordinary and turn it into something funny. There is a “hidden funny” behind every little event and situation you come across in daily life. Looking at situations with a different perspective is a very valuable life skill and fosters creativity! So next time your umbrella gets broken in the rain, well… look at yourself with a smile.

Second tip: learn from the maestros and watch more comedies, read humorous books, study funny people, go and see live clown shows, slapstick, gags, stand-up comedy and more. We know the importance of different styles of learning, so when you get an immersive lesson in humour by watching comedians, this is definitely valuable. Watch different styles, maybe coming from different parts of the world, to find out what you like, and also the different approaches in different cultures and subcultures. My favourite ever are the old ones like Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, Louis de Funès, Peter Sellers, Annie Fratellini, Jacques Tati, Totò, Lucille Ball, Nola Rae and Gardi Hutter, to the very recent clown Léandre Ribeira. Indeed, there are very few women, and this is another chapter!

The third tip is to be very careful not to offend others by overdoing it, and be very careful not to mix up the difference between funny and mean. To be funny doesn’t mean to make fun of others; first at least you have to make fun of yourself. Then you are allowed to play with others: to have fun with, not to make fun of. It is a huge difference. To offend others is a big risk, as we don’t know everyone, and we don’t know other people’s boundaries, their panic zones and their sensitive areas. That’s why we need lots of empathy and listening to other people. Even then, the risks stay and sometimes it happens that you touch people in the wrong way. It’s also important that you are able to say sorry and to learn from that.

Those who practise the language of humour are constantly looking for the right balance of sensitivity, which varies according to who is in front of them, and the environment in which they are embedded, continuously communicating and observing, always ready to correct the course, like a modern satellite navigator of the human soul. The communication of humour is all about listening.

Being funny and giving humour a voice is more about being generous, being open, truthful and giving – to share with others something that is part of your being. It’s about underlining some elements in a different or opposite way, being provocative about those things, making people think differently, or putting a little voice inside other people which questions things: being ourselves and opening a window into our humanity.

First, you need to be humble and make fun of yourself; looking at your weak points and making fun of those things is very hard. But this is one of the keys. If you first don’t make fun of yourself in an honest way, you will not be able to pass this on to other people.

Using humour in educational settings

But I also think that, as with other learning tools, humour might not be for everyone. Some people don’t like it, or don’t see the advantages of using it as a tool. I think that each of us needs to feel it, to make it our own; to create your personal touch, you cannot just copy and paste. A sense of humour is very personal, and for me very much connected with rhythm and music. More generally is the ability to catch the funny side of things, even when at first glance it seems that there is nothing to laugh about. It implies a certain amount of irony or self-irony, but it can turn into a lethal weapon if it is used against another person, ridiculing them. In this regard, humour can become an aggressive tool through mockery of the other person, and definitely should be avoided.

So, as mentioned above, we need to be careful how we use it and not to turn irony into sarcasm, especially in an educational context. In educational activities a lot of humour is maybe not possible to plan for, and it is more to do with the way we are in front of people and set the ground for learning. It is more about the attitude we have, than the skills we want to use.

But it is also possible to plan where to insert humour on purpose, for example in the introduction of some educational activities. It can make a huge difference while introducing an activity to put in some extra funny elements, or just a cartoon line before a PowerPoint, or a funny image in your flip chart presentation, which will connect with the subject you will talk about later, or to start a session with a short, funny movie. These things should come naturally and not be forced too much. To force humour causes the opposite effect… well, maybe not always, but we need to keep it in mind! With humour you can easily and directly reach people’s hearts, but this can be done with a gentle caress or with a knife.

But if you are thinking about some crazy, so-called “funny energiser”, well… I have a different opinion about those, which I can talk about when we sit in front of a cup of coffee ;-)

Being able to smile about ourselves not only improves learning but also preserves us from possible aggressive self-judgment and a load of negative emotionality, which would add to that arising from the difficult situation we are trying to deal with.

It is a language to reach people, to break the ice, to build trust in a group, for example during an international youth exchange, or in a partnership building activity. The way we build trust within the group and in the learning environment is fundamental for the learning process. Humour can be one of the colours that supports learning, and that’s why it has different ways and sides, like in the storytelling where you could use fantasy, comedy or the dark side. It is just one tool, not the goal itself!

The motivation for laughter is not gendered but humour is different between genders, and the content of humour can bring gender issues to the foreground of attention. I think that if we look back in history, as women we could not even act in theatres, but in the traditional circus, clowns were also taking women’s roles, so we started to be “free” much later than men. We have many more superstructures that prevent us from really being ourselves and from being accepted. I discovered there are studies[5] that suggest men are better trained in humour because they have to impress women and make them laugh, while women have many other elements to catch men’s attention. It seems that humour is also a sign of intelligence and many women believe, or were taught, that they become threatening to men if they appear too bright. So it could be that in some way, men do not want women to be funny. They want them as an audience, not as rivals.

But we need to underline that gender is not only about men and women, and that this is a much bigger topic to explore. As mentioned before with humour, you open people’s hearts and you therefore have responsibilities. In my experience, the way in which you do this also changes according to gender, because we have different experiences, communication ways and sensitivities.

In my experience, I can say that for me it is more natural to have an expressive sense of humour, more physical in form instead of using words and language. This is my personal way, my direct way of communicating with others and to overcome my shyness. That’s why I think it is important to take into consideration the composition of the trainer’s team, as probably a good team has a distribution of different humour styles, just like the other competences.

A conclusion?

A conclusion?

Well, if you have arrived at the end of these pages, keep in mind that these are my opinions, and in any case, humour is an instinctive language, at least for me, which is born I don’t know exactly where, but it can be cultivated like a beautiful flower. True humour is simple and natural, as instinctive as a breath.

You can make people laugh with a word, a tumble, an unusual accessory, a situation, and sometimes,

You can make people laugh with a word, a tumble, an unusual accessory, a situation, and sometimes,

but it takes a lot of talent, you can make people laugh with nothing”,

Annie Fratellini.[6]

[2]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277263780_Humor_y_cultura_correlaciones_entre_estilos_de_humor_y_dimensiones_culturales_en_14_paises.

[3] https://thekingisalive.wixsite.com/fergalbarr/single-post/2018/01/21/humour-barely-acknowledged-by-youth-work.

[6] Annie Fratellini was a French circus artist, singer, film actress and clown.