Socio-economic inequalities in political engagement: the consequences of limited citizenship education within vocational education and training

by Bryony Hoskins

11/12/2017

The 2016 review of the implementation of the 2010 Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship (EDC) and Human Rights Education (HRE) brought to attention the issue of disadvantaged youth and the inequalities in provision of EDC/HRE to this group across Europe. Although such inequalities can already be found earlier in a young person’s education experience (Hoskins et al. 2017), it was the lack of quality provision within the vocational education and training sector which was particularly highlighted. Typically across Europe, it is the most disadvantaged students (measured by socio-economic status, ethnicity and migrant status) who undertake the vocational routes in education (Hoskins et al. 2016),[1] and for this reason disadvantaged students are particularly affected by both the quality and quantity of HRE/EDC provision when undertaking these qualifications. At the same time, it is these young people whose voices are heard the least and who suffered the most during the recent economic crisis (ibid.).

The Council of Europe (2017) analysis of the summaries of replies from 40 member states’ ministries of education to the review of the implementation of the Charter highlighted the inequalities in provision of EDC/HRE between students who undertake vocational education and training, compared to students taking academic qualifications. In some European countries, this is referred to as different school tracks. Just over one-third of countries had either none or scarcely any reference at all to EDC/HRE in their education laws, policies and strategic objectives for their vocational education and training, compared to about 10% of countries who lacked these references for academic formal education. For those countries that had participated in the last two rounds of the review of the Charter (2010 and 2016) the situation was identified as getting worse, with 17 countries reducing or removing references to EDC/HRE within their countries’ vocational education and training.

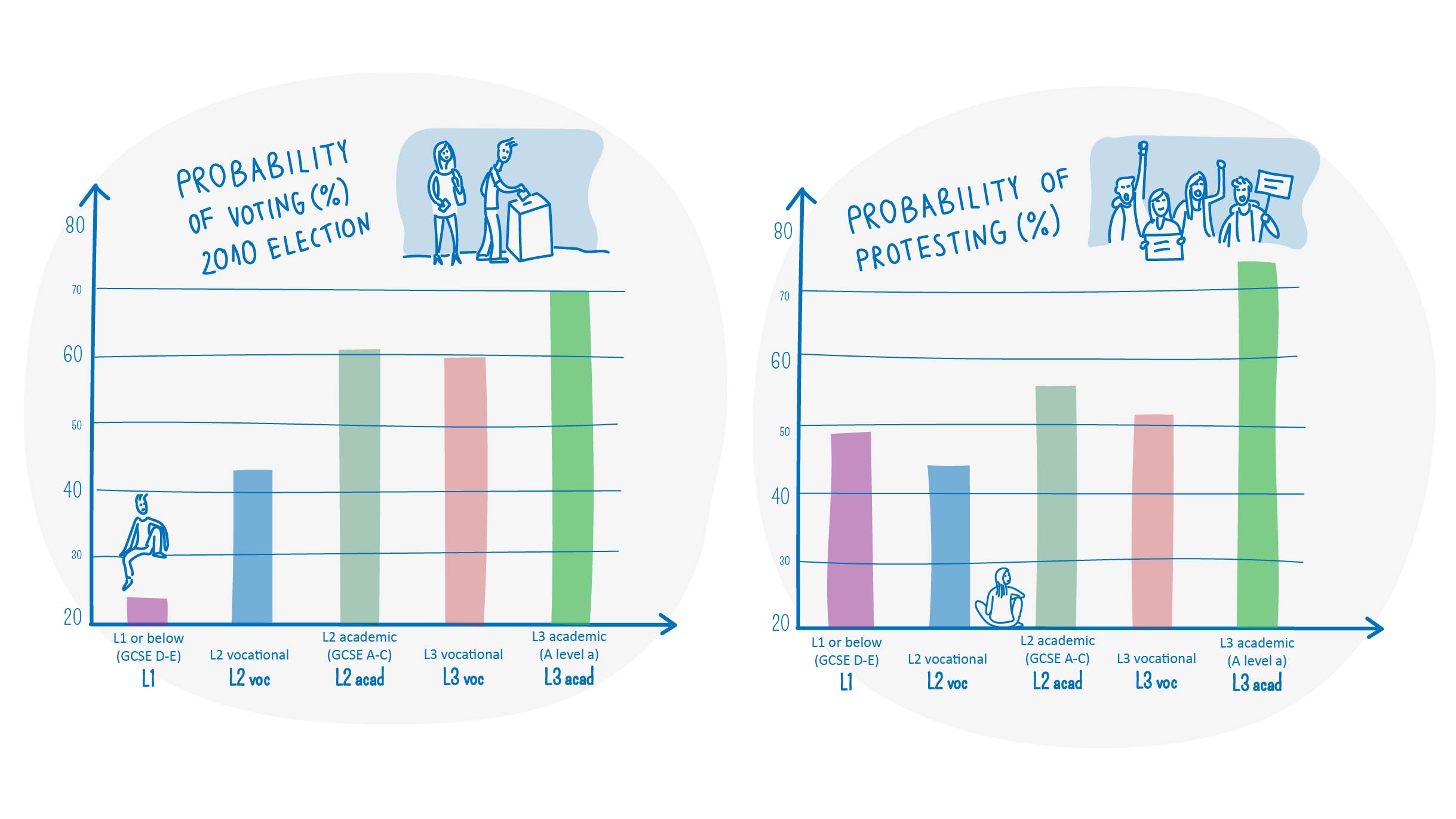

The ministry responses help to explain the results of recent research across 24 European countries, which find that young people who have taken a vocational education pathway across Europe are much less likely to politically engage than students who have undertaken general/more academic education (van de Werfhorst 2007, 2009). Nevertheless, it is reasonable to ask how researchers are sure that it is the vocational education experience that is influencing these results and not their prior education experiences or socio-economic status. In order to establish whether this is the case, it is necessary to analyse longitudinal data. This means data that are collected from the same individuals at different points throughout their life-course, including their early experiences of education and later on into adulthood. We have analysed data like these for young people living in England in our recent research and found some nuances regarding the different education pathways that young people undertook and their effect on political engagement (voting and protesting).

© Illustration by Siiri Taimla

Before we look at this analysis, I will explain some of the details about the vocational education system in England. VET in colleges in England, in particular those offering Level 1 and 2 European Qualifications Framework (EQF) qualifications, has been held in low prestige and is undertaken typically by young people from the most disadvantaged backgrounds. The usefulness of these qualifications in gaining employment in the UK has been questioned (Wolf 2011). VET qualifications in England are focused on skills for specific employment and contain very little in the way of general education. It may well be that students taking VET qualifications may also take or retake general qualifications in English and maths but it is very unlikely that they are offered, or choose to take, a specific citizenship education qualification (Hoskins et al. 2016). Young people in England can choose to take VET qualifications from the age of 15 to 16.

To analyse the effect of undertaking academic and VET on voting and protesting we have used the English Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study dataset. The study includes data from a cohort of young people aged 11 and 12 (Year 7; first year of secondary school) when they were surveyed for the first time in 2003. This cohort was then surveyed every two years until 2011 (Round 5). The data were collected from a nationally representative sample of 112 state-maintained schools in England. We used data from Round 5, when pupils were aged 19 and 20, and thus when most had either started working or had moved into higher education. We also used the data from Round 2 (when respondents were aged 13 and 14) to identify the baseline of young people’s intentions for political engagement prior to selecting vocational or academic education pathways. We included in the model for the analysis measures of gender, ethnicity, socio-economic background and main activity of the individual (at university, other education and training, unemployed or working). Adding these elements to the analytic model makes sure that the characteristics of students do not influence the overall results. The analysis we conducted is called logistic regression (if you are interested in more details of the data or methods, please see Hoskins and Janmaat 2016).

© Illustration by Siiri Taimla