Showing yourself(ie)

by Maria Schreiber

12/06/2018

What young people do with, in and on social media might seem strange and dangerous to grown-ups. But fear not! In this article, I will point out how their media practices are related to how our ways of connecting with each other have changed with digitisation and networked media. I will show how visual communication has become one of the most important modes of communication, and finally dive a little deeper into what all this has to do with youth, identity, peer-group conflicts and #bodypositivity.

How we connect in a digital age

How we connect in a digital age

With the arrival of the smartphone on the mass market about 10 years ago, our ways of communicating changed. On the one hand, the possibilities for interpersonal communication have expanded: we can be constantly connected to each other and can interact in real time, even if we are far away from home, depending on a data connection, of course. On the other hand, the transformations are maybe less fundamental than they seem: there are many continuities in how we interact with each other – because what we do and who we are online is not completely detached from our everyday lives. In its early days, the internet was perceived as cyberspace, as a parallel world where we can be whoever we want to be, for better or worse. Yet this has changed: during the last 20 years, networked communication has become more affordable, devices more mobile and digital communication deeply ingrained in our everyday practices.

Showing and sharing

Showing and sharing

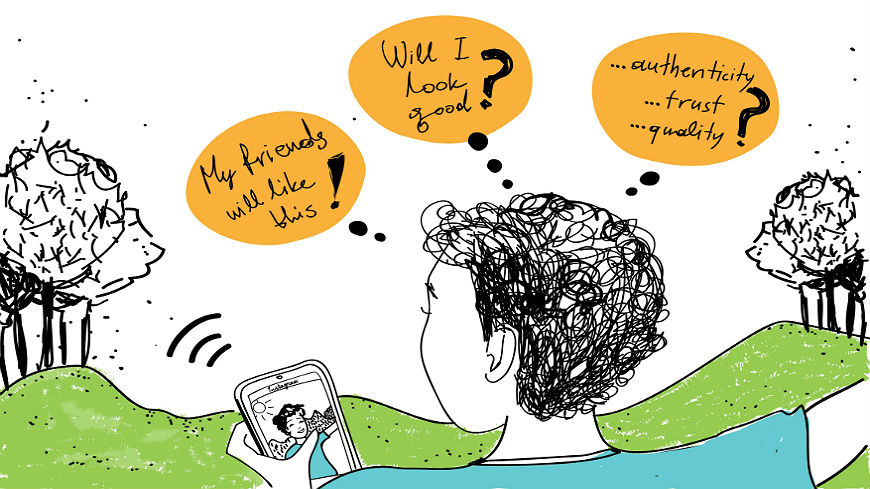

As a recent German study shows (ARD ZDF Onlinestudie), interpersonal communication remains one of the most important and time-consuming things we do online. This includes either reading, looking at or scrolling through what others have shared, or chatting, posting and showing things ourselves. These everyday communicative interactions became habitual and natural to us very quickly and are seldom reflected upon. Yet the media tend to portray sharing practices on social media mostly in negative contexts such as hate speech, mobbing and seemingly narcissistic selfies.

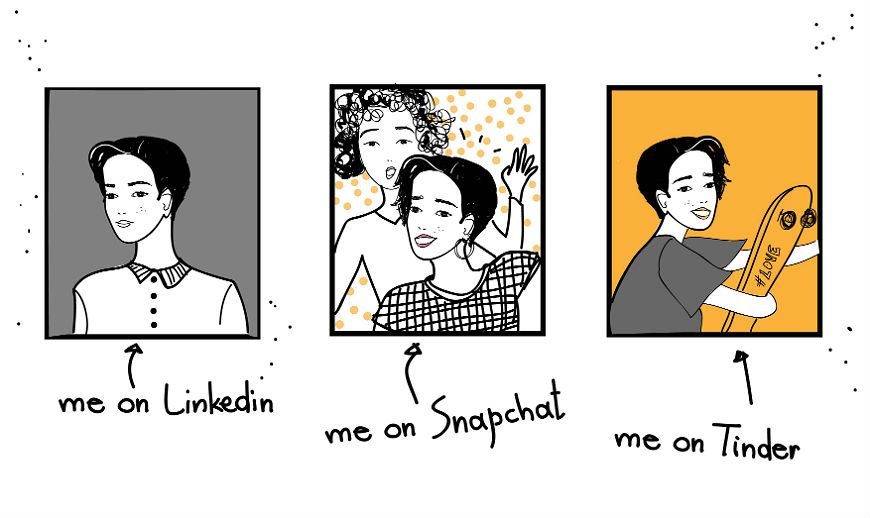

What some of these discussions tend to overlook is that there are also a lot of continuities in how we communicate with each other. In 1959, sociologist Erving Goffman came up with the term “impression management” to describe what we constantly do in our everyday lives. We interact with other people according to where we are and who they are to us – how we dress, how we speak, how we sit depends on the context we are in. Having a cup of coffee with our partner in bed is a very different situation to having a cup of coffee with a potential client in an office space. We show different aspects of who we are in different settings to different people. The same holds true for social media: while we send grimacing, blurred selfies to our best friends on WhatsApp, we will probably prefer to show a rather polished version of ourselves to our followers on LinkedIn.

Ever since the internet reached the Western mass market about 20 years ago, interpersonal communication was one of the most important functions it offered – internet relay chats, forums and different forms of online gaming were introduced early on. What has changed? With growing bandwidth and the constant development of hardware and software, digital communication became increasingly multimodal. After it began as a mainly text-based way of communication, it quickly became possible to embed pictures, videos, visualisations, interactive elements, and so on.

Talking through pictures? Learning to see

Talking through pictures? Learning to see

Overall, our visual communication has intensified: personal photography expanded from quite an expensive family practice to an individual ephemeral practice of catching moments. Cameras with high resolution are now embedded in smartphones, so we have them with us all the time, wherever we go. Also, they are constantly connected online and allow us to immediately share something that we have seen. While the sharing process in earlier times was time-intensive and expensive, it is now free, or included in flat rates, and instantaneous. Interestingly, a lot of the types of pictures that we have always taken are still important – babies, birthdays, weddings or the classic holiday pics – yet the quantity has changed, and some new genres like food porn, the aestheticised documentation of food and drinks one consumes, and selfies have become popular. Moreover, pictures are not only shown in photo albums or picture frames. We now “talk to each other” through images more often, not with sentences and letters, but with shapes, colours and compositions.

Visual expression has actually been a basic human need throughout the history of mankind. It is something we usually learn to do or just do before we start to write, but drawing or painting is later on often dismissed as a quite useless skill. We are taught what words mean, even what they are in different languages, we analyse articles and speeches, but seldom receive any formal education for our visual communication skills.

With the recent “democratisation” of photography and instant visual communication through smartphones, it has become clear that most of us actually can and want to express ourselves visually. Moreover, most of us now have the tool to do so right in our pocket. Digital media can enable creativity and expression, allow us to show what we find important and beautiful in quite cheap and easy ways, and, most importantly, to share these expressions with others. With the shift of everyday visual communication to the smartphone, photography has become an individual practice – a smartphone usually belongs to one person, and not to a whole family. As the 2014 study “Net Children Go Mobile” shows, there are cultural differences regarding the age at which children or young people get their own smartphone, on average between 10 and 12. In Brazil for example, more children have access to mobile devices than European kids. While in Europe internet access in schools is generally very common, Italy and Belgium have the lowest rates of access to internet in schools. There are of course families who cannot afford smartphones or data plans at all, yet more than 80% of young people in Europe between 16 and 29 use the internet on a daily basis, most of them through mobile devices.

Clearly, access to and ownership of digital devices is crucial for young people, as they no longer have to borrow cameras from their parents and be very careful. I myself remember when I got a quite cheap camera as a teenager and took many useless and fun pictures with my friends, my dad became quite angry once we had them developed because I had “wasted” the film. With the networked camera, we have all become media producers, which can be especially empowering for young people. We regained ownership of how we want to frame, capture and show the world – or did we?

Who am I?

Who am I?

Pictures allow us to mirror our embodied appearance, and to express ourselves stylistically and aesthetically. This is especially important for youth cultures, because during adolescence people grapple with questions of identity and belonging – who am I, and who are my friends? What kind of person do I want to be? What can I do, what do I want to do? These questions of affiliation and distinction are often negotiated on an aesthetic level. Since “youth” became a relevant phase of life in the 19th century, young people have always paid considerable attention to how they show belonging or distinction through clothing, hair, make-up, etc. The body therefore also becomes a canvas for expression. So how do social media and visual communication become relevant?

The increase of visual communication means an increase in visibility of things that have been framed as “private” for a long time – food, socks, pets and naked bodies. Through social media, our understanding of “publicness” and “privacy” has shifted. It is not either/or but has become more differentiated. In my own research, I conducted in-depth interviews with teenagers and users who are 60 and older about how they show and share pictures with their smartphones and which platforms and apps they use. I also visually analysed pictures they shared to learn more about the content and style of their visual communication practices. My main aim was to understand similarities and differences in sharing practices of young and old people, to overcome simple binaries like “digital natives” vs “digital immigrants”. Indeed, there were some recurring themes, for example the organisation of closeness and distance in relationships through apps. A group of teenagers, for example, explained to me that they had very fine-tuned differentiations in the WhatsApp groups; sometimes two groups may only differ by one person who is included in one group but excluded in the other. Also, in platforms that are framed as rather more public, there are possibilities to fine-tune if a certain photo album from a certain party becomes visible to the grandmother or not.

The level of visibility of young people on social media is often deemed to be “too much” and “too explicit” by the media. But while bodies and faces are certainly not the main content of shared photographs, they are definitely the ones that are most debated. Body pictures influence the way we think about our own bodies and what we think is normal or beautiful. In this regard, pictures shared on social media can become dangerous yet also empowering. Unrealistic, polished and edited body images can generate unrealistic expectations about one’s own body and invoke insecurity, especially in teenagers whose bodies are changing and evolving. Yet at the same time, there is also space for alternative body images and for campaigns that enforce body positivity, a positive, open-minded and tolerant attitude towards all kinds of body and gender images, through spreading non-normative pictures.

There is no single, causal effect of what images on social media do. It always depends on context. In one of the most important studies on teenagers and networked media (with the fitting title of It’s complicated), researcher danah boyd shows how broad the variety of things teenagers do in, on and with social media is. Yet there is one common theme: parents, educators, and decision makers rarely take time to really listen to them and to try to understand how media practices are relevant in their lives. For example, while there was or is a lot of moral panic and rush to judgment about selfies being narcissistic, young people’s opinions on how selfies are relevant to them is rarely heard. Yes, sharing pictures can become dangerous – when a nude picture is made public, for example; on the other hand it can become empowering when one discovers, for example, that there are a lot of other young men who like to try make-up. And, finally, sharing pictures is actually quite mundane and unspectacular most of the time, for instance when pictures of new socks, cute dogs or sunsets are shared, seen and liked.

It remains important to raise general awareness about how messages of any kind are transmitted with specific audiences in mind and how they are produced for specific media. Some media producers such as journalistic institutions might aim at being objective. Other influencers are popular exactly because of their subjectivity. While we have already learned to be sceptical about the “truthfulness” of some media, such as advertisements, social media still has an aura of authenticity to it – and what our best friend posted definitely has to be true.

One of the most important tasks for youth and media practitioners and educators is to activate not only young people but all people to be critical about media production – no matter whether it is professional or amateur – and to identify and reflect on what the criteria or characteristics of trustworthiness and quality might be. For example:

motivating young people to observe their own media use and critically reflect on it;

teaching them how media production works on a large scale, and making complex economic and technical entanglements more transparent;

explaining how information is crucial for acting as a responsible citizen within democracies; teaching them about other cultures and media systems to show that living in a democracy is not a given;

asking how they inform themselves and which media they use;

discussing what trust, authenticity and quality means to them with regard to media;

letting them produce their own media to understand how media production works on a small scale;

using critical pedagogy as a means of education;

in short: raising awareness of how media content, aesthetics and visibilities are constructed and are subject to cultural and economic power, and how they cannot be taken for granted.