What can we learn from outside the youth field?

by Calin Rus

09/10/2019

There are many examples of meaningful and useful adoption into youth work practice of theories, models and tools developed in other sectors. Some of them are probably best reflected in the flagship publications of the Youth Department of the Council of Europe addressed to trainers, as well as in all the T-Kits. A good example is the new version of the T-Kit on intercultural learning, which shows up-to-date connections with recent developments in intercultural research.

Is there more to do? Of course, and there are various reasons to still learn from fields like management, social sciences, media or IT, but also from closer fields, such as formal education or community development. Two of the most obvious reasons are that, on one side, social reality is evolving and there is always a need for new ways to address the new challenges and, on the other side, these fields are also in evolution and their new approaches and tools can be a valuable resource for the youth field.

Below are three examples of recent advancements in formal education, management and social psychology which I consider relevant for the current context and concerns of youth work. But let’s not forget that youth work is also providing inspiration for other sectors, as many teacher training programmes, including those implemented by the Council of Europe in South-East Europe, or training activities aimed at empowering Roma disadvantaged communities, such as the ones developed in the framework of the ROMED programmes, use methods and tools developed in the youth field.

Developing values without indoctrination and paternalism

Developing values without indoctrination and paternalism

Many people who know me would probably expect me to propose the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture as inspiration for the youth sector when it comes to the promotion of values. I will leave this task to other colleagues, considering also that I noticed with joy that the Reference Framework was mentioned in two articles in the previous issue of Coyote: Intercultural learning – A solution in the post-truth era and What will be the next ladder of youth participation? Instead, I would like to suggest youth trainers to take inspiration from the debates within the formal education sector regarding the legitimacy of promoting values and the ways this should be done to avoid perceptions of indoctrination and a moralising paternalistic discourse.

Youth work is self-declared as value-driven and committed to the promotion of human rights, democracy, intercultural learning, inclusion, empowerment and participation. Yet, the societal context is different now, compared to the previous decades. We have young people exposed to political messages from sources validated through elections which voice opposition to valuing cultural diversity, legitimate authoritarian or “illiberal” forms of democracy, or question human rights and the values of equality and non-discrimination. The argument that building a society based on the values of human rights, democracy and the rule of law brought to Europe the longest period of peace in over five centuries provides little appeal to most European young people today, for whom accounts of war seem referring to a distant past. Also, many youth organisations are now working with young refugees, coming from undemocratic societies in which human rights are presented as part of a Western ideology of domination. Youth trainers should therefore be equipped to go beyond the reflection on values promoted in interactive human rights education activities, such as the ones Compass is providing, and be able to address resistances to the legitimacy of promoting values in general. Recent debates in the formal education sector, in events organised by the Education Department of the Council of Europe, but also at the level of the EU, as illustrated by the EU Council Recommendation on promoting common values, inclusive education, and the European dimension of teaching, adopted in May 2018, are a good source of inspiration and reflection.

Is the promotion of values a legitimate aim of formal and non-formal education activities? Should youth workers explicitly promote valuing democracy and cultural diversity, along with human dignity and human rights, or should they just support young people to reflect on their values and make their own choice? Although these seem as opposed alternatives, it is, in fact, a false dilemma: the promotion of not just any value, but of the values of human dignity, human rights, democracy, equality, justice, fairness, rule of law and appreciation for cultural diversity should indeed represent an essential focus of non-formal education activities targeting young people, regardless of their background, but this should be done by stimulating critical reflection and not by imposing a certain discourse.

Youth workers are used to promoting human rights as universal, inalienable, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated. In a similar way, it can be argued that there is a close interconnection and interdependence between human dignity, human rights, democracy and appreciation for cultural diversity. If one is missing, the others will be affected and the result will be a society in which we would not like to live. Supporting young people to reflect critically on the consequences of disregarding the fundamental European values is a powerful tool to enhance commitment for these values.

Youth NGOs reflecting on participatory frustration and organised hypocrisy

Youth NGOs reflecting on participatory frustration and organised hypocrisy

Work and research in the field of management can also be valuable for youth workers, even when it refers to re-evaluation and transfer of classical theoretical models. Thus, a classical model developed decades ago (Hirschman 1970), called Exit, Voice and Loyalty model has more recently been adapted and adjusted to explain political behaviour and migration and it can be equally useful to understand the motivations of young people to participate in civil society and politics, to counter the “participatory frustration” and prevent adhesion of young people to populist, extremist, xenophobic anti-establishment movements.

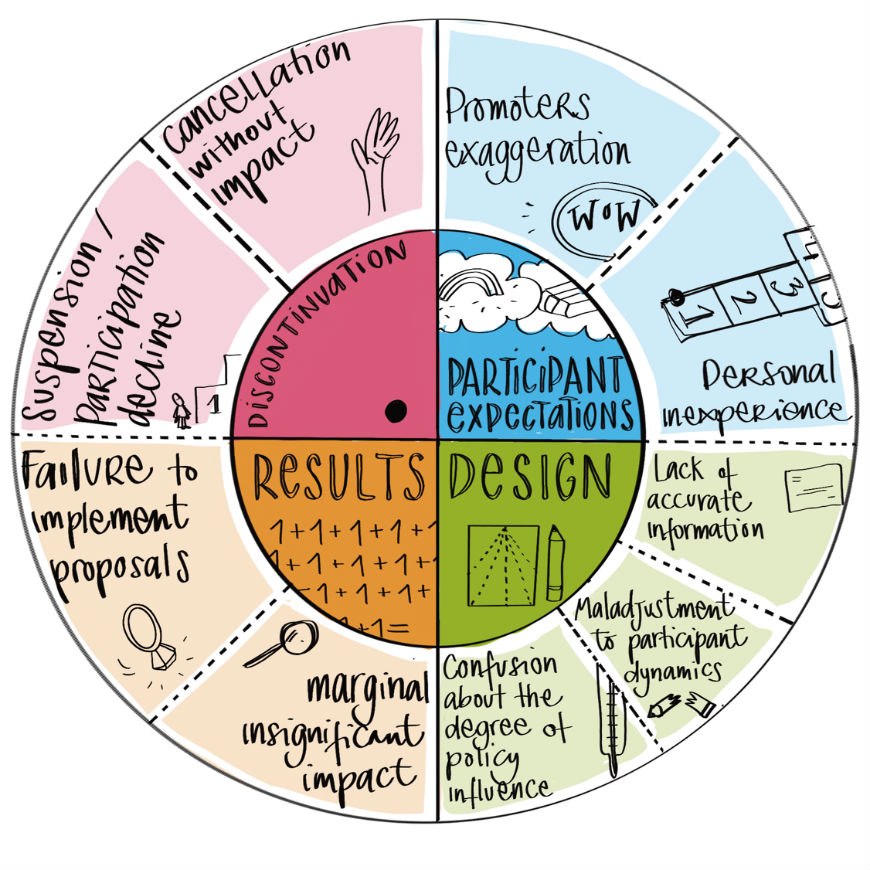

While the original model argued that people confronted with dissatisfaction in a social setting should opt between “voice”, expressing their discontent and requesting change and “exit”, abandoning the group or entity generating dissatisfaction. Transferred from an organisational context to society, this would mean that when they perceive society as not being able to give them confidence in a better future, young people can choose between protest or emigration. We have seen a lot of these over the last decade. More recent research shows that there is a third option, “silence”, meaning apathy and conformism, but also shows a more complex picture of possible motivations for one choice or another. The “wheel of participatory frustration” (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2019) illustrates the main sources of frustration related to participatory processes, including frustration generated by inflated initial expectation, by the design of the participatory mechanisms and the failure to adjust them when needed, by the use of the results of the participatory processes and by the discontinuation of those processes. This can be a useful tool for reflection on youth organisations and youth activities. A proper analysis followed by consequent adjustment of youth work can prevent participatory frustration and maintain loyalty and commitment.

Another interesting concept initially developed in organisational sociology and more recently expanded to other fields, such as international relations, is “organised hypocrisy” (Brunsson 1989). The concept describes the adaptation and survival mechanisms of the organisations which prioritise maintaining a positive public image and legitimacy when confronted with contradictory requirements from internal and external factors. Such a contradiction may appear between the need to respond to the needs of the organisation’s beneficiaries, as stated in its mission, and the need to conform to requirements and norms imposed from the outside. The systems where organised hypocrisy appears manifest superficial, insubstantial and often ineffective reactions. The Intercultural Institute of Timisoara used the concept in a critical analysis of the EU programmes and projects supporting Roma inclusion but the theoretical model can also be useful for youth organisations. It would be a useful tool for youth organisations to reflect on how much their work is actually driven by their declared mission and by the interests and commitments of its members and to what extent it is determined by, sometimes confusing and contradictory external influences, such as policies of local authorities or the priorities of national or European funding programmes.

Overcoming prejudice through indirect intergroup contact

Overcoming prejudice through indirect intergroup contact

Many youth workers and trainers, active either at local level in multicultural settings, or at international level, are well familiar with the social psychological research based on the so-called “contact theory”, or “contact hypothesis”. Although criticised by some researchers, meta-analysis studies (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006, 2011) prove the benefits of reducing intergroup prejudice through direct contact and co-operation between members of the groups concerned, under certain conditions. This has already proved its value for youth work, including recently in work involving young refugees and locals, as illustrated, for example, by the experience of the NICeR project, involving refugees and local young people in preparing together a theatre and music performance, or by experiences led by the Intercultural Institute of Timisoara and its partners, including the Roma NGO Nevo Parudimos, bringing together Roma and non-Roma young people in disadvantaged communities. Recent research demonstrates, however, that there are also positive effects on reducing prejudice and on improving intergroup attitudes and relations of various forms of indirect contact (Dovidio et al. 2011; Stathi et al. 2014).

There are three forms of indirect intergroup contact which can be very useful for youth trainers, considering the specific situation in various regions of Europe: extended contact, vicarious contact and imagined contact. Extended contact means interacting with someone from your group (someone whom you perceive as similar to you) who is in a close relationship, for example friendship, with a member of a group perceived as significantly different. Vicarious contact consists in observing someone perceived as similar to you interacting in a positive way with people from the other group, while imagined contact is about imagining oneself interacting with an outgroup member.

Research (Christ et al. 2014; Wagner et al. 2006) proves that anti-minority or anti-migrant attitudes are more frequently negative in areas with fewer opportunities to meet members of these groups. At European level, opposition to migration is stronger in the countries with the smallest presence of migrants.

Thus, training methods, at local level, as well as in an international context, can be adapted to make effective use of these forms of indirect intergroup contact, including via the internet, in order to stimulate reflection and awareness and to promote a positive view on cultural diversity, while reducing prejudice and xenophobia. The virtual world and social media offer unprecedented opportunities for direct and indirect contact between young people belonging to groups perceiving each other as different, in conflict or in opposition, but what research on intergroup contact teaches us is that contact can reduce prejudice and improve perceptions only if certain conditions are met. This is why the role of youth trainers is essential in framing contact, whether direct or indirect, face to face, virtual or imagined, in a way that generates positive outcomes.

The examples above prove that there is still a potential for youth trainers to look for inspiration and new approaches in other fields. And these are just a few examples; there are many other very relevant models and tools out there to incorporate in youth work. New developments in psychology, media studies, communication science, or IT can be equally useful. This means that youth trainers should be prepared to use their “autonomous learning skills” to stay in contact with new developments in related fields and explore their possible use for the youth field. The Training of Trainers programmes provided by the Council of Europe Youth Department and by the Youth Partnership should support youth trainers in discovering ways in which research results and theoretical models can become tools for youth work. The Youth Partnership should also continue to provide support, both in terms of publications that facilitate this process and in terms of opportunities for trainers to exchange ideas and experiences on the use of theories, models and tools from outside the youth sector.

References

References

- Brunsson N. (1989), The organization of hypocrisy: talk, decisions and actions in organizations, Wiley, Chichester.

- Christ O., Schmid K., Lolliot S., Swart H., Stolle D. Tausch N., Al Ramiah A., Wagner U., Vertovec S. and Hewstone M. (2014), “Contextual effect of positive intergroup contact on outgroup prejudice”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 111, No. 11, pp. 3996-4000.

- Dovidio J., Eller A. and Hewstone M. (2011), “Improving intergroup relations through direct, extended and other forms of indirect contact”, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 147-60.

- Fernández-Martínez J. L., García-Espín P. and Jiménez-Sánchez M. (2019), “Participatory frustration: the unintended cultural effect of local democratic innovations”, Administration & Society, March 2019, Sage. (NB: needs login)

- Hirschman A. O. (1970), Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Pettigrew T. F. and Tropp L. R. (2006), “A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol. 90, No. 5, pp. 751-83.

- Pettigrew T. F. and Tropp L. R. (2011), When groups meet: the dynamics of intergroup contact, Psychology Press, New York, NY.

- Rus C. and Nestian O. (2014), Roma inclusion on the labour market: from organised hypocrisy to effective measures. Intercultural Institute of Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania.

- Stathi S., Cameron L., Hartley B. and Bradford S. (2014), “Imagined contact as a prejudice- reduction intervention in schools: the underlying role of similarity and attitudes”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology Vol. 44, No. 8, pp. 536-46.

- Wagner U., Christ O., Pettigrew T. F., Stellmacher J. and Wolf C. (2006), “Prejudice and minority proportion: contact instead of threat effects”, Social Psychology Quarterly Vol 69, No. 4. pp. 380-90.