Why do we need EDC/HRE?

by Rui Gomes

11/12/2017

Where are we now with EDC/HRE with young people? Do we still need it?

Human rights education and education for democratic citizenship, because they share fundamentally similar objectives, approaches and values (while also being distinct), remain as important to young people as they have ever been – probably more than ever before in this century. This conclusion is dictated by reality more than anything else. The realisation that Europe is in the most serious human rights crisis since the cold war and the concern that our democracies can go backwards raise more than alarm bells about how democracy and human rights are being practised: they should also be understood as a fundamental concern about our societies’ capacity to renew democracy and to renew commitments to universal human rights.

The hesitations and tensions that cut into the flesh of many European societies about combining universal human rights values with national or cultural particularisms (or patriotisms) – freedom free from solidarity or freedom with solidarity – are a stark reminder that human rights and democracy are not innate – not even to Europeans (!). The ritual proclamation of human rights as part of European values does not make them better known, respected or understood, unless we apply a strictly critical-thinking approach. We have too often entertained fictional stories about human rights education. These stories are supported by consensus about the importance of human rights education and about its role in the founding of a common ethical framework above national educational priorities. This is visible in recent documents such as the Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education or the Competences for Democratic Culture, but also in various commitments, notably the Council of Europe Action Plan against Violent Extremism and Radicalisation Leading to Terrorism. But, as the reviews of the application of the charter testify, the reality is much more diverse: progress is observed but regress is also present – a lot more can be done, and better.

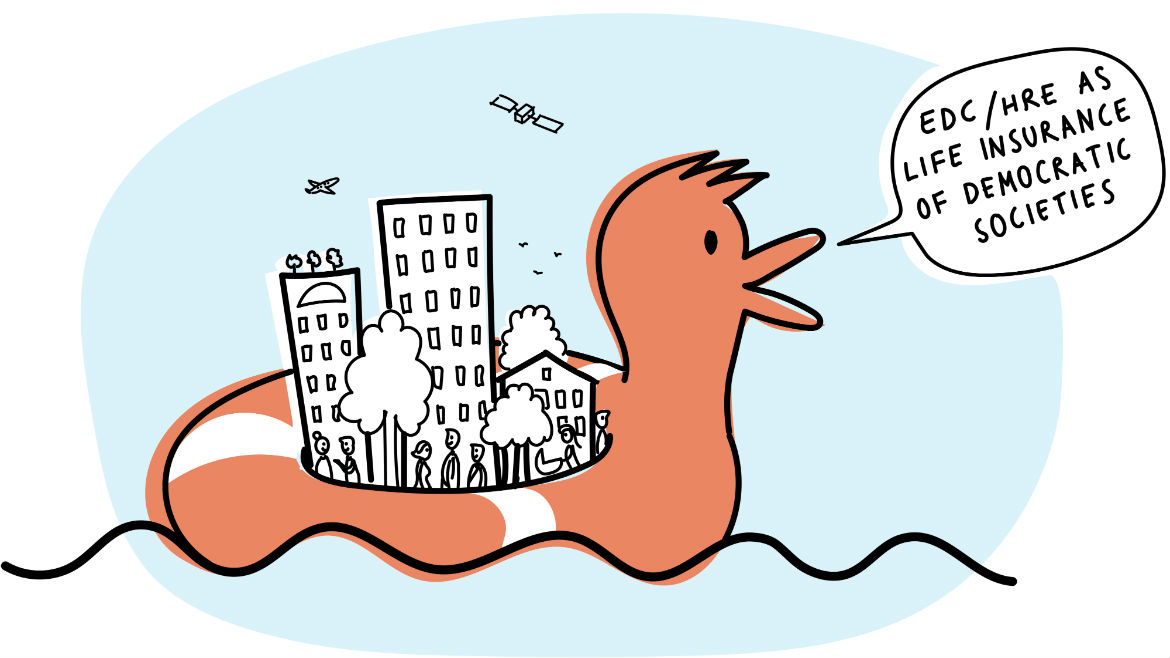

Learning and applying human rights and democracy are effective ways of preventing violence, radicalisation and terrorism. Indeed, they are recognised as the life insurance of democratic societies, respectful of the equal dignity of every human being. But this recognition is also, implicitly, the admission that the practice of human rights education has remained secondary to many other priorities of educational programmes and policies. The utilitarian understandings of its function, for example to foster employability and to prevent radicalisation, do not really contribute to the recognition and development of its role in supporting children and young people in learning about, learning through and learning for human rights. In other words, to support the understanding of human rights as a “network of interlocking attitudes, beliefs, behaviours, norms and regulations” as part of the foundations of living together.

Human rights education is therefore not made irrelevant because of its supposedly widespread practice nor by its replacement by any other programme. And while it is not necessary to have specifically labelled courses or programmes about human rights education, it remains fundamentally more important than ever that young people have possibilities to learn and practise human rights values. Clearly and explicitly.

The call of the conference, Learning to Live Together: a Shared Commitment to Democracy, for a renewed commitment of the Council of Europe member states to human rights education is more than just a call for the current programmes to continue, but also for them to be extended to other groups of learners and to be deepened, especially in recognition and support by public authorities. It is also the admission that what we have may be good, but it is not sufficient.

The feedback we receive from non-governmental youth partners in the Human Rights Education Youth Programme testify to the same need: their actions are often ignored, sometimes recognised and seldom supported. In several situations their work is also a risk: we are especially concerned by testimonies of practitioners who are afraid of openly addressing human rights issues, in both school and out-of-school contexts. Self-censorship is of course understandable as a protection attitude. But it remains deeply unsettling to any educator or human rights activist because it is an indicator of the state of human rights education for many practitioners: lauded in international human rights fora but largely ignored or neglected in specific educational and social contexts.

There are also very successful examples of policy and practice taking good account of human rights education with young people – the No Hate Speech Movement campaign has also been an excellent occasion to popularise what human rights education is about – but, all in all, this also confirms the appropriateness, the relevance and the necessity to address human rights in an explicit manner with young people. Because there cannot be human rights education without human rights.

The democratisation of human rights is probably the most important mission for human rights education in the 21st century.

© Illustration by Siiri Taimla

In your opinion, does EDC/HRE nowadays respond to the needs and realities of young people? How to make it possible?

Young people across Europe are concerned about their future, about succeeding in their transition to being autonomous adults aspiring to pursue their academic and professional dreams and aspirations. But this is not all. Young people, more than any other age group, are also concerned about pursuing and realising their dreams and aspirations in shaping a society according to their values, not only having their aspirations shaped by the realities of markets and performance in complex societies. Building and living social relationships differently remain appealing priorities, which, nowadays, also have to include the relationship with the preceding generation and the one coming after us, and with the planet itself. Human rights education provides the necessary orientations for a globalised conscience; also when that conscience manifests itself in anxiety and phobia, the awareness of the fundamental equality in the dignity of all human beings sets the boundaries of the debate. It also plays a fundamental role in reassuring young people who find themselves in vulnerable situations, either because of the view of the majority of society on their identity or status, their socioeconomic situation or the precariousness of the formal links with the societies in which they live.

For these young people, as for many other people in similar situations, human rights are a guarantee. And human rights education offers the possibility for young people to be active protagonists in their struggle for emancipation and to strengthen the ties that unite them. The symbiotic relationship between learning “about”, learning “for” and learning “through” human rights is what makes its strength, including strength in the relationship between learners and facilitators of learning. Preserving that relationship is thus essential for the discourse of human rights education to be credible and to be taken up by young people themselves.