The opportunities for youth services in the digital age

by Victoria Nash

30/11/2018

Based on her keynote address to the Youth Partnership’s symposium, Connecting the Dots: Young People, Social Inclusion and Digitalisation, Victoria highlights the major areas to be explored.

From reading daily news stories, it could easily be assumed that the internet’s main impact on young people has been the corruption of impressionable minds via exposure to worrying forms of violent or sexual content. Although each headline may accompany a legitimate news story in which the well-being of youngsters is indeed at risk, they tell us far more about the media’s response to new technologies, and, perhaps more interestingly, about public fascination with scare stories concerning the internet and its supposed risks for children.

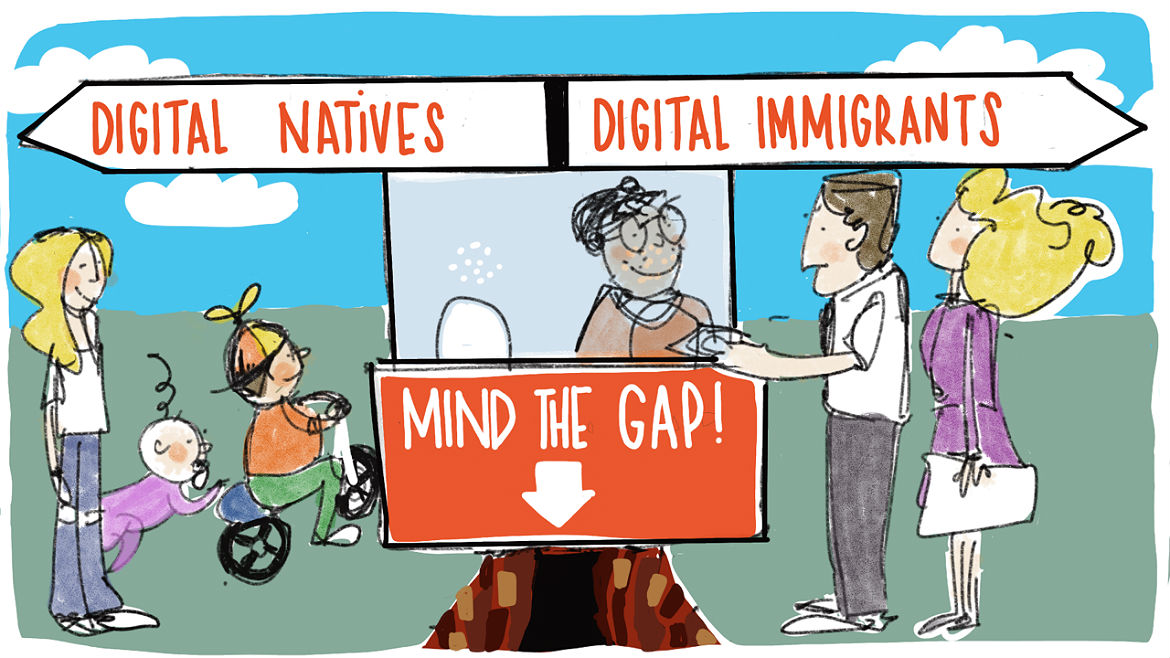

One possible reason for the moral panic surrounding youth internet use is that young people are often presumed to be more expert users than their parents or educators. Characterised as the difference between “digital natives” (those who have grown up with the technology) and “digital immigrants” (those who come to it later in life), this assumes that all children born since the early 2000s are equally skilled at using technology. Unfortunately, this assumption is damaging on two fronts. First it encourages us to think that it’s impossible for the older generation to keep pace with young people’s use of digital technologies, and second, it occludes many variations in internet use and access between children. With the rise of smartphones and tablets, youth growing up in Western nations enjoy near-universal access to the internet from an increasingly young age, but there remain considerable differences and inequalities in the extent and types of use. This is an important proviso for youth services, who must ensure they provide for all rather than marching towards a “digital-by-default” approach.

Against this backdrop, it is particularly important that policy interventions support strategies for dealing with risk rather than simply avoiding them. Strategies that can build young people’s digital resilience might help them deal with problematic content when they are exposed to it, or understand more about the risks of seeking it out, rather than bluntly preventing exposure such as through internet filters. It is vital that young people can understand and implement positive behaviours online, and this means receiving more than ICT training, or even media literacy training. It means, for example, ensuring that lessons for personal development educate young people about the risks and fictions of pornography and the responsibilities of partners in creating personal sexual images, or that citizenship education relates to the challenges of calling out hate speech online and tackling bullying amongst peer groups. Again, this is an area where youth services might develop expertise and leadership, particularly as trusted intermediaries who often support young people through challenging life events.

Policy and media focus on the risks of harmful online content for young people is further problematic in that it also fails to note the rise of new forms of risk which digitalisation is bringing to the young. The extensive flows of personal data that we leave in our social media wake may prove risky for today’s youth, even with the added protections of the GDPR. As societies, we are just beginning to understand how concepts of privacy and a private life may be altered by our apparently voluntary surrender of vast troves of personal data to big corporations. Regulatory efforts to ensure that key decisions taken about our individual futures are not affected by algorithmic biases may still struggle to prevent the myriad ways in which each one of us is served a different online experience based on the profiling of our personal characteristics. Similarly, we have yet to figure out how the transition from teens to adulthood, and the development of maturity will be managed with a fully available public record of youthful misdemeanours, outlandish opinions and regretted behaviour constantly available to hold us back. How these risks will affect our life opportunities remains to be seen. Vitally, any efforts to monitor and minimise risks on such issues will need to focus not just on individual encounters but on the broader economic context in which digital experiences take place – the logic of “platform capitalism” may well underpin all the opportunities that digitalisation is bringing for young people, but it is also largely responsible for these new risks, and will likely resist efforts to substantially limit our data-sharing activities in the future.

In this world of new risks and new opportunities, the role of youth organisations must be greater than ever. While research suggests that some traditional civic organisations have been slow to adapt to the needs of digital youth, competition from grass-roots organisations, often operating across and beyond local boundaries means many young people are engaged in social movements online. The rise of virtual organisations such as Occupy, Anonymous and platforms enacting social change such as Kiva, should serve as a reminder that there is an immense opportunity for youth services to harness young people’s energy and motivation to act. However, youth services have to ensure they still offer something relevant, exciting and via channels that young people want to use for communication; it is no good simply setting up a Facebook page, when all your users are on Snapchat. Youth services have traditionally offered support, mentoring, social activities and personal development for young people; but if well-designed for the digital age they may also be able to harness some of the energy and desire to make a difference that other online organisations thrive upon. Youth services for the digital age might thus do more than support our young people; ideally they can even help them change their world. If they can do this, while also ensuring support is not redirected away from those who are less skilled or less confident “digital natives”, youth services will continue to contribute towards an immense social good.