Enter! – in and out

On roots, sources, origins and impact of Enter!

by Nadine Lyamouri-Bajja

08/04/2020

When I was asked to write this article about the origins and impact of Enter!, I heard myself saying yes before I could even think about it. How could that happen? First of all, I do not believe I’m particularly gifted in writing, secondly, I don’t have the time… But this yes came from deep inside, because it was about Enter!

So here I am.

The Enter! project remains one of the most powerful and meaningful youth work and training projects I was lucky enough to be involved in.

I started to work as an educational advisor in the European Youth Centre of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg in early 2006. Just before that, in October 2005,

In the French media you could read headlines such as “Is the Republic burning?”, or “When the neighbourhoods are burning”.

Some weeks after the violent confrontations between the police and young people in so-called “disadvantaged neighbourhoods” or “popular neighbourhoods”, the political debate starts shifting towards the “identity crisis” of multicultural young people raised in these neighbourhoods, about their confusion between their countries of origin and their French identity or citizenship, about integration policies and equal opportunities, about discrimination and communitarianism (a word used in a sociopolitical context to explain that more importance is given to the community than to the individual).

I remember sitting in my office one night with Peter Lauritzen1 discussing youth participation, violence, exclusion and discrimination in relation to young people in the suburbs and areas with fewer opportunities. I remember us talking about how youth work could possibly reach out to those young people and areas. And I remember us wondering about how an organisation such as the Council of Europe could possibly contribute to this work, as the situation was far from concerning only France.

Enter! begins

Enter! begins

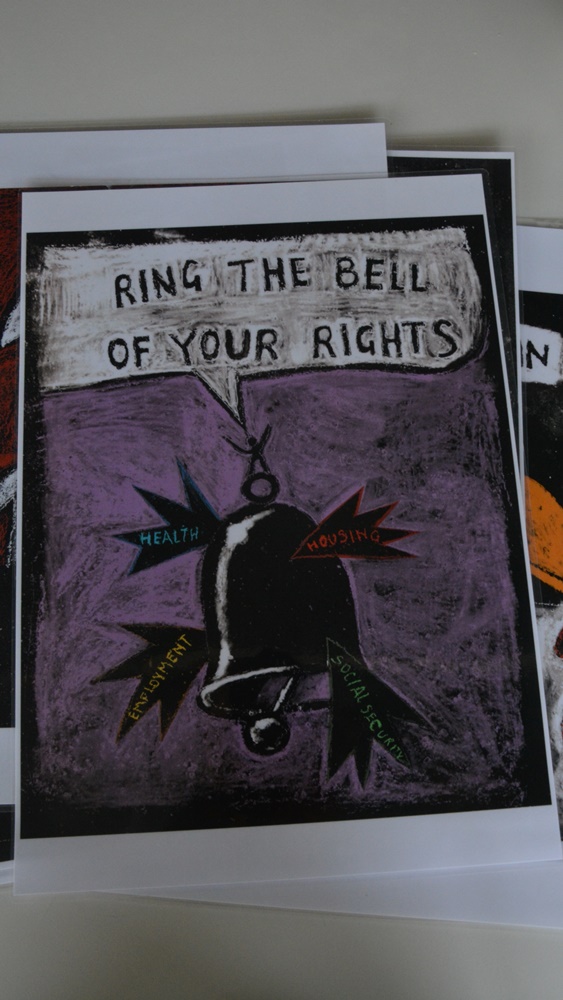

I was therefore particularly enthusiastic and motivated when the Enter! project on the access to social rights of young people from disadvantaged neighbourhoods was set up as a response to the growing concern of the European Steering Committee on Youth (CDEJ) and the Advisory Council on Youth (AC) about the inequalities and challenges related to social cohesion and inclusion of all young people, and especially those situated in “disadvantaged” neighbourhoods across the 47 member states of the Council of Europe.

The project aimed at “developing youth policy responses to exclusion, discrimination and violence affecting young people in multicultural disadvantaged neighbourhoods”.

I was directly involved in the preparation and implementation of various activities and steps of Enter!, but the most impacting for me, is the Long Term Training Course (LTTC)2.

The name of the project, “Enter!”, was given by the preparatory team of the first LTTC as a reference to inclusion, to being welcome to come in, as an invitation, and last but not least, as a reference to the button on the keyboard in line with the e-learning dimension of the course.

Central questions for us

Central questions for us

Among the many questions that came up during this training course, here are the ones that both the preparatory team, the participants and the young people involved mentioned:

The use of the concept “disadvantaged”: in the first LTTC, as well as the Enter! youth meetings and in the local projects, various youth workers and young people questioned the use of the word “disadvantaged”, as they could not identify with it as regards to their neighbourhoods. They described it as patronising and minimising potentials, the richness in community work and collective organisation. Although the word disadvantaged was chosen to describe the neighbourhoods as such, and not the people living in the neighbourhoods, this remained a debatable issue throughout the project.

- The strong diversity of challenges and situations in those neighbourhoods from one member state to another, and sometimes from one region to another: although all participants could agree on the key issues of discrimination, exclusion and violence, the state responses and the access to basic needs varied greatly.

- Social conditions and culture: in most cases, a direct link was drawn between the poor conditions in disadvantaged neighbourhoods and the population living there. Disadvantaged neighbourhoods are often inhabited by people with a migration background (even if sometimes third generation), refugees, asylum seekers or Roma people3). This often led to clear discrimination based on the locality and related to the type of population.

- Co-operation between Enter! participants, their sending organisations and local authorities: in the case of the LTTCs, participants were asked to develop local projects contributing to enhancing access to social rights for young people. The success of the projects did not only depend on the high investment and commitment of participants, but also on the actual involvement of their sending organisations, and furthermore on the opportunity to co-operate closely with local authorities. Although various seminars and meetings, as well as the co-operation with the Congress of Local and Regional authorities, who supported with close collaboration, co-operation remained one of the main challenges throughout Enter!

- Reaching out to actual community leaders: as in some other specific projects, one could wonder about the capacity of an organisation such as the Council of Europe to reach out to local communities in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. In other words, did Enter! manage to work with the concerned target group? Access to information about such a project, the capacity to work and communicate in English or French, the capacity to fill in a complex application form, the time and capacities to develop local projects, all these criteria could contribute to favouring an exclusive group of participants.

What made this project so special?

What made this project so special?

Through the range of activities and formats in Enter!, the project aimed both at reaching out to communities through competence development and empowerment of youth workers, and at making a change at policy level through the recommendation and co-operation with local authorities. Finally, the beneficiaries – the young people in the neighbourhoods – were directly involved as well both through the local projects developed in the LTTC and through the youth meetings and the youth week. This cross-cutting approach, combining a bottom-up and a top-down approach, was both innovative and inclusive by itself.

I remember when the participants of the first LTTC described their project ideas, with a high level of emotion, pride and commitment. Their engagement was not necessarily new. But formulating their project ideas through the lenses of social rights and human rights, on the basis of existing instruments, and with the support of the Council of Europe, made a difference.

I remember hot discussions around a session on “human rights”, and how some participants mentioned that Roma young people in some settlements did not even have access to drinkable water, so that access to education, employment or leisure was not even to be mentioned.

I also remember the permanent challenge of talking “about” certain groups of young people, rather than “with” them. The Enter! youth meeting and youth weeks, as well as the local projects developed within the LTTC, partly contributed to changing this paradigm, but the general challenge of fully including the concerned communities remained throughout the project.

Enter! surely did impact at various levels. Among the various impacts at youth work and youth policy level mentioned in the study on the Enter! project, here are some of the impacts that could be seen:

Enter! managed to raise awareness at European, national and local level about the situation in disadvantaged neighbourhoods on the one hand, and about social rights and instruments to protect social rights, on the other.

As a result of the first Long Term Training Course, participants created the YSRN (Youth Social Rights Network), which continues to function as an international youth NGO, runs study sessions and international youth projects, and is strongly involved in networking and advocacy on social rights.

The Enter! youth meetings brought together young people, policy makers and field workers to discuss access to social rights through various perspectives, with various languages and with a highly solution-focused approach. Hundreds of young people contributed directly or indirectly to the development of the Enter! Recommendation CM/Rec (2015)3 on access of young people from disadvantaged neighbourhoods to social rights, which was adopted by the Committee of Ministers in 2015.

Direct impact?

Direct impact?

One could wonder if Enter! did directly improve access to health, education, employment, leisure, decent housing or non-discrimination for young people across Europe… there surely remains a long way to go, but both at youth work level and at policy level, milestones have been laid, and people’s competences are still being developed to contribute to social change.

The youth sector of the Council of Europe is currently proceeding to review the implementation of the recommendation, which most probably will not show the direct impact of the Enter! project and recommendation. But it could surely focus on the fact that working on access to social rights needs time and commitment, as well as constant reminders to take access to social rights seriously. The topic is far from being over just because Enter! is. Many local organisations that got involved at all stages of Enter! are taking the recommendations, the lobbying work and the educational and youth policy work on board to continue advocating for access to social rights of all young people. Véronique Bertolle’s article “Entering the Enter! Youth week”, published in this issue of Coyote, gives a beautiful overview of the diversity of organisations, challenges and young people concerned. It also gives hope about the fact that the work is being pursued.

As for myself, I keep as a conclusion that context is everything. That it is rarely about people and capacities, but often about the resources and support they are given. And that the more challenges, the more resilience.

References

References

Lauritzen P. (2008), Eggs in a pan: speeches, writings and reflections, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

1 Peter Lauritzen (1942-2007) was the former Head of the Youth Department. More can be read about Peter here or here.

2 I am referring to the first LTTC (2009-11). Since then, two further series of the LTTC have taken place.

3 The term “Roma and Travellers” is used at the Council of Europe to encompass the wide diversity of the groups covered by the work of the Council of Europe in this field: on the one hand a) Roma, Sinti/Manush, Calé, Kaale, Romanichals, Boyash/Rudari; b) Balkan Egyptians (Egyptians and Ashkali); c) Eastern groups (Dom, Lom and Abdal); and, on the other hand, groups such as Travellers, Yenish, and the populations designated under the administrative term “Gens du voyage”, as well as persons who identify themselves as Gypsies.