Sexuality and relationships of young people with disabilities

by Marijeta Mojasevic

21/04/2020

Most of my work experience as a social worker has been with young people, and I am also a person with acquired disabilities. These experiences give me a position from which I can share some insights into the state of social rights for young people with disabilities, particularly regarding sexuality and disability.

“Sexuality and disability” and “disabled person relationships” are very familiar terms to most people, but their implications can be difficult to understand for people who spend most of their lives in the shadow of their societies’ prejudices and stereotypes. And while it seems that prejudices and stereotypes can cross the borders of every state without passports, they seem very often to be trapped behind the line of a person’s state of mind.

Sexuality is a very broad term, but for the purpose of this essay it can be defined as:

a central aspect of being human throughout life encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles and relationships. (https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/)

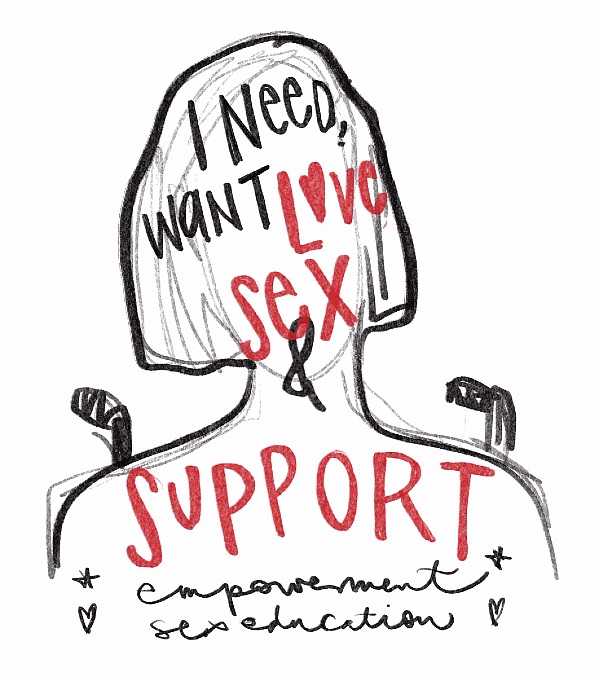

This definition should be used in every single case on this planet, but when it comes to persons with disabilities, it is always hidden by shadows of prejudice and fear. It seems that many young people who were born with or acquired any type of mild to severe disability are seen as asexual beings or just simply: they have more issues regarding their health condition, so their sexuality never comes to the fore.

A broken piece of society?

A broken piece of society?

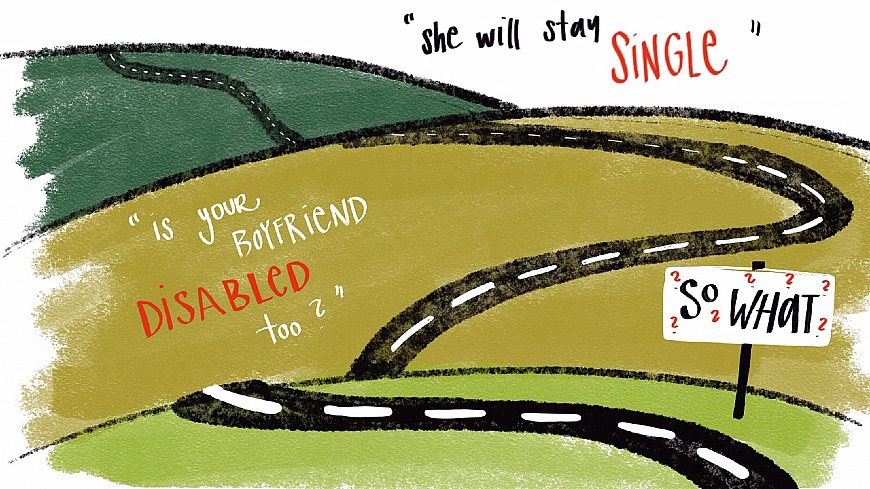

More than half of my life I have identified myself as a person with acquired disabilities, but most of the people who live in our society identify me as a broken piece of it (society) which cannot be fixed. When it comes to my sexuality and relationships, I’ve come a long way from “she will stay single”, to “is your boyfriend disabled too?”, to the point where I am today – where my disability is a fact in my life which is not dictating my relationship status. But many people with disabilities in my country, which is Montenegro, are not so fortunate, and for many countries in Europe the situation is more or less similar. Why does a culture which urges the elimination of discrimination have a nourishing effect on it?

Part of our tradition in Montenegro lies in the attitude that healthy young people should find an equal partner of the opposite sex; if that is not the case, it is not approved by many members of our community. For many years I was trying to work out why I was rejected by some really intelligent and open-minded guys who were simply attracted by my sexuality but could not forgive my not-so-visible disability.

I would help myself by remembering one scene from my past. Namely, I was with my cousin when I met my friend who is a wheelchair user. Sitting together and chatting, he found her very interesting. Later he told me that she is cute but such a pity she is a wheelchair user; it would be very hard to live with her, even to have children together. And this is the simplest explanation for my situation: I would find the answer in the words that were never said to me, but I would feel them deep inside.

Why isn’t sexuality enough to build a consistent relationship when it comes to persons with disabilities?

Because it is not considered important that a healthy person date a partner who is right for them, but a partner who is healthy enough to have children with, who in turn will also be healthy.

Place for love, romantics and pure sexual attraction

Place for love, romantics and pure sexual attraction

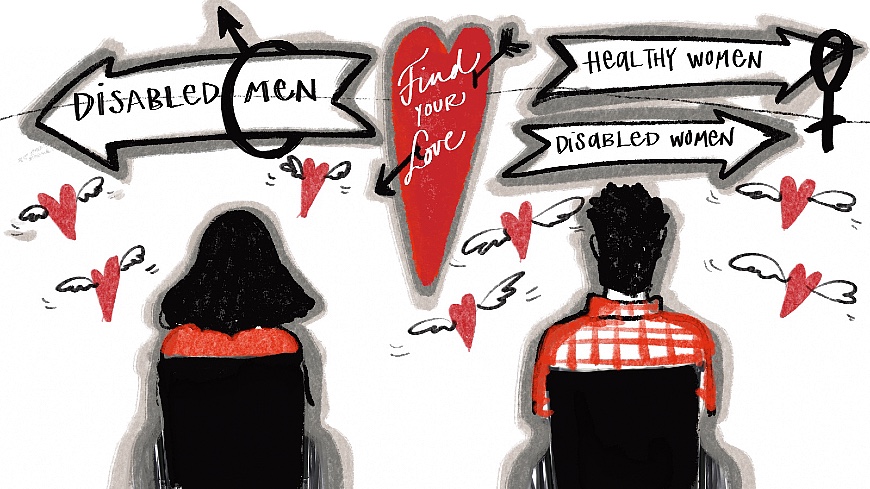

Most of us have many romantic experiences and feelings of love and sexual attraction, but ask yourself where the place for these things is in the story of young people with disabilities. It is very rarely the case that a non-disabled person will accept a disabled one. And if that is the case, it is more approved by tradition that a healthy female should accept a male with a disability, because of reproduction. Patriarchal society has made us believe that a hierarchy in relationships should be made respecting the male, for example my female friends who are wheelchair users should only date guys who are in the same or similar position.

My constant questions are:

Why couldn’t we be mixed, disabled and non-disabled?

Has the 21st century, this ordinal number, arrived to convince us that difference is possible, that we are more mature as a society?

Maybe we are asking too much from an ordinal number, even if it is a century. But you can never ask too much by expecting that people can change, and so can social relations. They very often need to be pushed or pulled.

Fighting stereotypes and prejudice

Fighting stereotypes and prejudice

As a member of the European Network on Independent Living (ENIL), I became familiar with the international movement of persons with disabilities by participating in a study session “Supporting young disabled people to explore sexuality and relationships as integral to their social inclusion and independent living” (https://enil.eu/news/lets-talk-about-sex/).

The knowledge I gained and the experiences that participants shared during that study session made me aware of the cruelty that stereotypes attached to any kind of disability were making to people similar to me. In my mid-twenties and being in a stable relationship, I knew that the relationship could be ruined if stereotypes win their battle, so my interest in the topic of sexuality and relationships of persons with disabilities was on my “to do list”.

While participating in the work of a task group dedicated to this question, and later taking charge of it, I found out that this topic is a “hot spot” in only a very few countries in the world, that is, just in those with stable social situations and high standards. The part of Europe where I live is not one in which I could use ENIL’s recommendation on including sex education within the inclusive education debate. By fighting stereotypes and prejudices, however, I could hope indirectly to influence this issue. In the task group, we started to use some of the recommendations from the study session, like the use of social media to highlight the topic of disability and sexuality and mapping existing campaigns on disability and sexuality. But after mapping the campaigns, we could not do very much except spread the news among a very narrow circle of people who were or could be interested in this topic. Should sex and sexuality of persons with disabilities be taboo or do we need to talk about it more in public?

I think that sexuality means a lot in the life of every human being, and being a person with disabilities does not make me less human. I think that, in the first place, prejudices and stereotypes need to be fought. But also we can make use of the Enter! Recommendation on access of young people from disadvantaged neighbourhoods to social rights, for example: “promoting comprehensive health, nutrition and sexual education and information for young people in order to support them in making informed decisions” (Access of young people from disadvantaged neighbourhoods to social rights (CM/Rec(2015)3): page 11). Because sex and sexual education is a question of health, it is not being seen as relevant to the fight against prejudice and stereotyping.

The same is true of the recommendation on “paying special attention to the health needs of especially vulnerable groups of young people experiencing multiple forms of exclusion (including young Roma and migrant women, young people suffering from poor mental health, young people with disabilities, young people with HIV, etc.)(Ibid., page 15).

In reality, isn’t the fact that we are not eligible to date simply a form of exclusion from social life, framing the stigma that says we are reproductively challenged and not “good material” for parenthood?

Finally, we should demand the best from the health service that it can offer and take advantage of the recommendation on “investing in the development and implementation of youth health programmes and crisis counselling services through educational, awareness-raising and support programmes on healthy and responsible lifestyles (addressing in particular any substance misuse, addiction, sexual and reproductive health, early, unplanned or crisis pregnancy, mental health, sport, nutrition, family and work perspectives and overall well-being) through existing public youth work, education and community institutions” (Ibid., page 15-16).

I always end a workshop for young people by using the same words: don’t judge. Maybe because I have been the object of many judgmental looks, opinions and attitudes in my life, I have learned that giving people an opportunity to be who they are is the best possible way to get to know them.

Stereotypes and prejudices can stop young people from meeting many great people, some of whom could be their future partner, just because their culture doesn’t have that dimension of tolerance and understanding of difference, for example, towards people with disabilities.

That is why I see the role of youth organisations and youth workers as essential, especially in reminding governments to ensure access to all social rights for young people with disabilities.