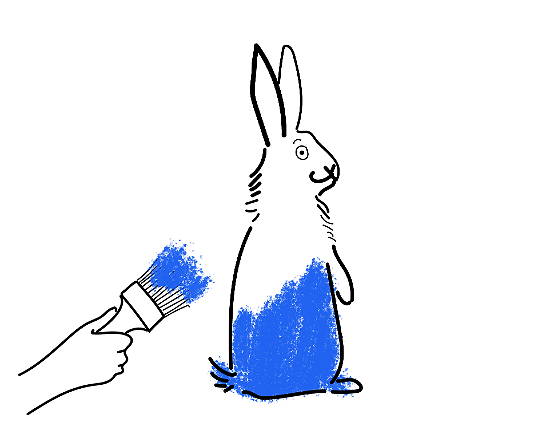

Pourquoi le lapin est bleu?

- Humour in training

By Mark E. Taylor

31/05/2018

Obviously the answer to the title question is: Parce qu’on l’a peint!

Q: “Why is the rabbit blue?” A: “Because someone has painted it!” - the sounds of the words “lapin” and “l’a peint” are the same.

Obvious? Yes, if you speak French to the level where simple word play is understandable. No, if your French is only very basic or non-existent. It is very easy to divide an international group of, say, Youthpass Contact Persons (YPCP’s) just on the basis of this “joke”. Funny, here; not funny, there; understood, here; not understood, there; etcetera etcetera. And you also have to deal with the mock protests of the French YPCP in the informal times, who claims JOKINGLY that the mere fact of telling this joke in this context makes a mockery of French culture.

A conversation about humour and trainers in training

Many of those points have been buzzing around in my Emmental brain for years, so I was very happy to accept colleague Simona Molari’s invitation to join her in an online chat about these subjects with the participants of the annual E+ Training of Trainers course. Luckily she and I had discussed the topic beforehand because she got sick on the day – but we agreed on most things. Sara Paolazzo had an enthusiastic conversational interviewing style and we covered a lot of essential points. Maybe it’s useful to share some of them with you here:

training in non-formal learning requires the creation of an atmosphere which helps people feel ready, take risks, maybe even feel comfortable with a certain amount of failure - humour helps to create that learning space

humour is risky in itself and can have the opposite effect of the aim of using it – this is often because the so-called humorous remark or action is not related directly to the context

humour often works because it is related to a shared set of experiences and/or references – this means that you can have great effects by using what is happening in the training course itself

trainers who make jokes about themselves, particularly near the beginning of a course, will help the process by showing their own vulnerability and thereby allowing participants to empathise with the situation

sometimes just about the worst thing you can do as a trainer is to use humour! For example, there are times when a group has to go through some tension or conflictual feelings in order to come out the other side and learn from the experience. A joke at that moment will destroy the learning possibilities. So, hold that space and see what happens

a trainers team does not have to be a team of jokers! Each trainer needs to make their own choice in the use of humour, to be authentic in their role and to themselves. A team works because of complementarity between trainers.

don’t try to make everything funny because, in the end, nothing will be funny! If you get the reputation as “the funny trainer” then no-one will take you seriously!

some trainers use humour in order to provoke a reaction from participants – if there is a good conversation at the end, this may be defensible; but you need to have a lot of experience to know how to handle those reactions!

I try to find a balance in order to reach the goal of being “seriously funny” – people enjoy things, even laugh, AND they get the point

listen to your belly and your “intercultural antennae” to check if your humour is really working – get feedback from other trainers and participants

I would be delighted to hear what YOUR thoughts are on all of this! What makes you laugh in training? What would you never do?

Some of you may have discovered a recent slim volume produced by the Partnership called Thinking Seriously About Youth Work. And how to prepare people to do it. A mammoth work, in 38 sections with some 40 distinguished contributors and, as Fergal Barr points out in his blog there is but one reference to humour in the whole book! Shurely shome mishtake?

In the European Training Strategy’s Competence Model for Youth Workers to Work Internationally there are no references to humour at all. You have to laugh or else you cry…

And finally

Thanks to those who write or give informal feedback. Next time we consider the “pataphysics of shape-shifting for beginners”…

Q: How many youth work trainers does it take to change a light bulb?

A: First, decide if changing the light bulb is an intellectual output, then formulate your KA2 strategic partnership goals.