Psychological first aid in youth work

by Alexander Rose

02/12/2021

Are you aware of what is coming? New wave of needs in youth work after Covid

Are you aware of what is coming? New wave of needs in youth work after Covid

Covid has been associated with a substantial rise in symptoms of mental health problems. The pandemic and the restrictive measures taken by governments worldwide are considered to have had a severe impact on young people’s mental health (Blanco-Donoso et al. 2020).

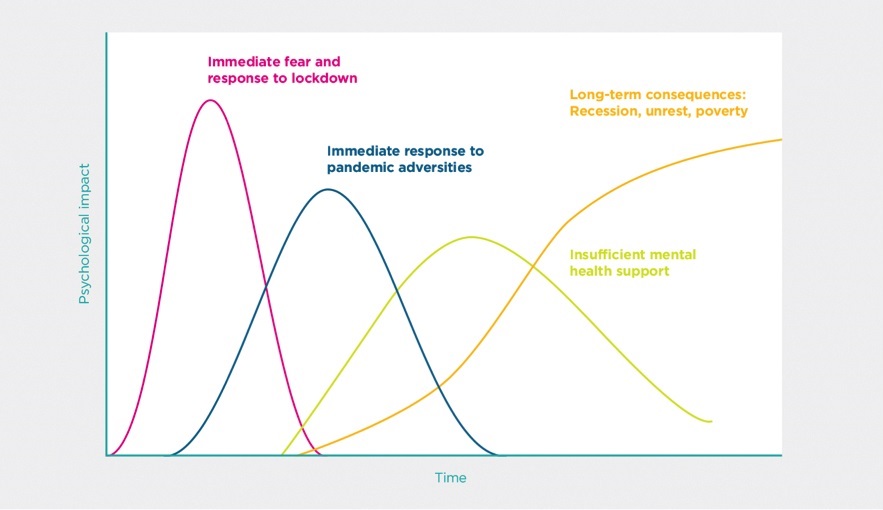

The ILO (2020) studied the immediate effects of the pandemic on the lives of young people (aged 18-29). According to their report, the impact has been particularly hard on young women, teenagers and young people in lower-income countries. Horigian, Schmidt and Feaster (2020) found that among young US adults (aged between 18 and 35) significant depressive symptoms in 80% of participants were appearing. “Alarming” levels of loneliness were associated with significant mental health issues, with approximately 61% of respondents reporting moderate (45%) to severe (17%) anxiety. According to the report (EU 2021), the third and fourth phases of mental health effects are only now beginning to play out, and may turn out to be the most consequential (see figure below).

Time horizons of key mental health effects of the pandemic

Source: Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic, World Happiness Report 2021.

The coronavirus pandemic’s psychological long-term impact is still unclear. Some examples of health-related anxieties still in the future might be people thinking they get infected, the chance of being hospitalised or dying, the probability of infecting others, and the possibility of loved ones being infected or dying. General anxiety could continue for some people after the pandemic ends, and obsessive-compulsive disorder is most likely to last in the longer term. As a result, related worry and fear amplify the risk of substance abuse, for instance. Symptoms of depression are shown by feeling meaningless in life, or by isolation and chronic loneliness (EU 2021).

The question of youth worker’s therapeutic role is on the table. My position, aligned with Cooper (2018), is that youth work has an explicit therapeutic orientation: therapy is accepted as part of the holistic approach where it meets a young person’s needs. Youth workers may provide formal or informal counselling, and approach mental-health related problems.

Youth workers have a privileged position also as observers in groups of youngsters. Because of continuous evaluation of their programmes and interventions, youth workers might be the first responders in mental health problems, together with the school system. If trained, with fine-tuning of youth workers’ view and having the necessary skills, they can efficiently respond to crises such as panic attacks, implement prevention and early intervention programmes, and activate referrals to mental health professionals.

Perhaps, in order to provide quality youth work, policy makers have to be courageous and recognise their value. Policy makers need to face the challenge of providing resources, both human and financial, provide specific training or include therapeutic staff in teams.

Training pills to improve a fine-tuned view

Training pills to improve a fine-tuned view

Emotional pain is not something that should be hidden away and never spoken about.

There is truth in your pain, there is growth in your pain, but only if it’s first brought out into the open.

Steven Aitchison (@StevenAitchinson (Twitter), 6.06.2018)

Coming myself from youth work for many years, and working now as a psychologist mostly with teenagers and in collaboration with youth workers in prevention programmes, I consider below some useful little “pills of information” to improve and sharpen our interventions.

What is the (dis-)Stress-Anxiety-Depression continuum?

What is the (dis-)Stress-Anxiety-Depression continuum?

Stress is what our bodies and minds experience as we adapt to a repeatedly changing environment, to life. “I am so stressed…” How many times have you heard, thought, or said so? What you are really experiencing there is that you feel incapable of managing all you are supposed to do: too much workload, too little time, and fewer resources as needed... that is DIS-stress.

When you perceive that a situation, event or problem exceeds your resources or abilities, your body reacts automatically with the “fight or flight” response. When (dis)stress builds up over time, you may experience irritability, pains, sleep problems, or a decline in performance. If stress is left unchecked, symptoms will worsen, causing forgetfulness, severe physical complaints, illness, feelings of anxiety, panic and/or depression. Stress, anxiety and depression are placed in a continuum, so the earlier we start doing something about it, the better.

How do emotions work?

How do emotions work?

Emotion, from the Latin emovere, from e- “out” and movere “move”. Emotions are inner energy, which guides us to do and act. Emotions can be divided into pleasant and unpleasant, but they are adaptive, and they provide information about our needs. For example, nausea prevents us from ingesting spoiled or poisonous food, or fear activates the fight-or-flight response, and love we need to create our affective bonds from birth, necessary for healthy growth.

We feel and place emotions in our body: in our stomach, throat or our back. These feelings are the way our emotions have to express themselves. These feelings need to be heard, in order to find out what we really need. We need to give space for feelings to express even if they are pleasant or unpleasant.

Proper emotional intelligence is achieved when we recognise our emotions, the emotions of others, and we are able to manage them, to hold them. To do this, it is interesting to know that the way we think affects what we feel. For example, if you think and believe that there is a high possibility of your loved ones dying of Covid, you may feel anxious, and as a result you may not leave your home or you will not let anyone get close to your loved ones, etc. If you can change your way of thinking about someone dying of Covid, with facts like “the World Health Organization reports X% of the world population has been vaccinated”, your anxiety will decrease, and it’s more likely you will not self-isolate.

More and more, youth work is including specific programmes and generic actions to develop emotional intelligence.

What are defence mechanisms?

What are defence mechanisms?

Defence mechanisms are psychological strategies people use to separate themselves from unpleasant events, actions or thoughts. These may help people put distance between themselves and unwanted (or unmanageable) feelings. Some defence mechanisms are denial, repression, projection, rationalisation, etc. These mechanisms have a function to protect people’s well-being. If someone is not prepared to face a traumatic event, these mechanisms are put in place. A defence mechanism can become pathological when its persistent use leads to maladaptive behaviour, resulting in an adverse effect on an individual’s social functioning, physical or mental health.

Due to Covid-19 we have all put in place many defence mechanisms. It is not our role in youth work to question them in our youngsters, but to make them aware and propose other more adaptive mechanisms to cope with stressful situations, now and in the future.

How does a youngster behave when he or she feels…?

How does a youngster behave when he or she feels…?

These are some common behaviours and feelings, which could indicate different stress-related situations and other problems related to the Covid crisis.

- Anxiety: the most common sensations are palpitations, choking sensation, changes in food intake, nervousness, restlessness, agitation, muscle tension, tiredness, fatigue, excessive worry, fear, and difficulty making decisions. In anxious situations, adolescents may appear extremely shy. They may avoid their usual activities or refuse to engage in new experiences. Or, in an attempt to diminish or deny their fears and worries, they may engage in risky behaviours, drug experimentation or impulsive sexual behaviour.

- Phobias: phobias are an identifiable and persistent fear that is excessive or unreasonable and is triggered by the presence or anticipation of a specific object or situation. It is compounded by shortness of breath, dizziness, lightheadedness, shaking, fear of losing control, and an increased, racing heartbeat.

- A panic attack: intense terror (a feeling that something terrible is going to happen), rapid heart palpitations or tachycardia, dizziness, shortness of breath, tremors or shaking, a feeling of unreality, and fear of dying, losing control or going crazy.

- Depressive mood: feelings of sadness, which may include crying periods for no apparent reason, frustration or feelings of anger, even over minor issues, feelings of hopelessness, emptiness or meaningless, being irritable or upset, and loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities. Sometimes, it can be difficult to tell the difference between ups and downs that are just part of being a teenager and a teen depressive mood. Try to determine whether he or she seems capable of managing challenging feelings, or if life seems overwhelming. Check also for self-harm and suicidal intention or ideation. It is healthy and responsible to talk about it; suicide is the second cause of death among young people aged 15 to 29 in Europe, and first in the US.

How can we help?

How can we help?

You, yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.

Buddha

- Notice the problem, recognise when somebody feels stressed or anxious.

- Pause and reflect. Take care of your own emotions. Ask your colleague to assist or help, and intervene.

- Listen openly without judging, so your group or youngster will feel picked up and listened.

- With the information given, reflect again. Do you need to act immediately, or do you have time to plan the intervention?

Need to act immediately (anxiety attack, for example):

-

- Take control, now you are in charge. Do you need more help? Find it!

- Create an emotionally safe space: separate the affected person from the group, but do not leave the group unattended (to work in teams is recommended).

- Use simple instructions. Being present and caring is a good way to help.

- Help the youngster to breathe, focus on the airflow in his/her body. Divert attention from thoughts by constant reminders to keep focused on the breathing or anchoring with the here and now (invite the youngster to identify something inside the room and describe it).

- When he/she feels better, more calm, talk about the situation and evaluate where it might come from, and ask for permission to discuss his/her/their problems within the team. Involve the youngster in the decision making.

- Find a long-term solution together with the youngster and/or group.

Time to plan:

-

- Talk about the situation and evaluate where it might come from, and ask for permission to discuss his/her/their problems within the team. Look for clinical psychologists if you notice the issues the youngster is struggling with are beyond your knowledge. Involve the youngster in the decision making.

- Find a long-term solution together with the youngster and/or group.

And always, after these situations, take care of yourself. Do not carry it on your back, it is not healthy, nor is it the best practice.

A good tool to deal with crisis, conflict and trauma during training was developed by Agnieszka Leśny and Carlos Bobbert. Here are links to Part 1 and Part 2. The Mental Health Foundation in the UK has also created a resourceful website in order to help during and after Covid times.

Youth workers and self-care

Youth workers and self-care

Self-care is how you take your power back

Lalah Delia (@LalahDelia (Twitter), 31.03.2021)

Da Silva and Neto (2021) mention that health and care professionals are experiencing higher levels of anxiety (13% versus 8.5%) and depression (12.2% versus 9.5%) compared to professionals from other areas. Blanco-Donoso et al. (2020) detail the psychosocial risks health professionals are facing at work during Covid, such as job stress, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, work–family conflict, or violence at work. We need to be aware and act accordingly. We need to prevent burnout. However, how do we do so?

Expand your resources: training in specifics like crisis intervention, emotional intelligence, etc. can help you feel more competent.

Implement supervision: this is the process whereby a team regularly discusses their work with someone experienced. Therefore, it is recommended to create interdisciplinary teams, share your concerns and problems with colleagues, supervisors and managers, and find solutions within your team.

On your own, you may:

- exercise, be active;

- eat healthy;

- make time for sleep;

- create and connect to a support network;

- learn and practise meditation techniques such as mindfulness.

Mental health and youth work go hand in hand, and youth work is a demanding profession. Therefore, if you have a lack of concentration, feel constantly tired and irritated, feel you have been working with lower energy and motivation, your self-esteem has diminished, I suggest you find a mental health professional in order to help you to recover and go back to work with youngsters. Your groups need you healthy!

Conclusions

Conclusions

Mental health problems don’t define who you are. They are something you experience.

You walk in the rain and you feel the rain, but, importantly, YOU ARE NOT THE RAIN.

Matt Haig (The Comfort Book, 2021)

Mental health affects everyone, from our youngsters to policy makers to youth workers. Our intervention as youth workers often lies on the borders of therapeutic work, and it is good practice to attend to our youngsters’ needs. In order to develop quality work with mental health-related problems, which are likely to appear more and more in the future due to Covid, youth workers need to acquire specific competences and skills. Together with working in interdisciplinary teams and enhancing co-operation between different professionals and resources may help struggling youngsters, or prevent them from developing mental health problems. Ah, and also take care of yourself!

Youth workers are in the front line, and our job can make a difference for many young people!

References

References

Banks J., Fancourt D. and Xu X. (2021), “Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic”, World Happiness Report, https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2021/mental-health-and-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Blanco-Donoso L. M. et al. (2020), “Occupational psychosocial risks of health professionals in the face of the crisis produced by the COVID-19: from the identification of these risks to immediate action”, International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances Vol. 2, No. 100003.

Cooper T. (2018), “Defining youth work: exploring the boundaries, continuity and diversity of youth work practice”, The SAGE handbook of youth work practice, SAGE.

European Union (2021), Mental health and the pandemic, www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/696164/EPRS_BRI(2021)696164_EN.pdf.

Haig, M. (2021), The Comfort Book” Canongate Books.

Horigian V. E., Schmidt R. D. and Feaster D. J. (2021), “Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among US young adults during COVID-19”, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 1-9.

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2020), Youth & COVID-19: impacts on jobs, education, rights and mental well-being, www.ilo.org/global/topics/youth-employment/publications/WCMS_753026/lang--en/index.htm.

OECD (2021), “Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis”, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/supporting-young-people-s-mental-health-through-the-covid-19-crisis-84e143e5/.

Silva F. C. T. (da) and Neto M. L. R. (2021), “Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis”, Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, Jan 10;104:110062.