Taking chances – dancing dances

The story of how dance improves young people’s access to social rights, personal development and quality of life

by David Aynsley

05/12/2019

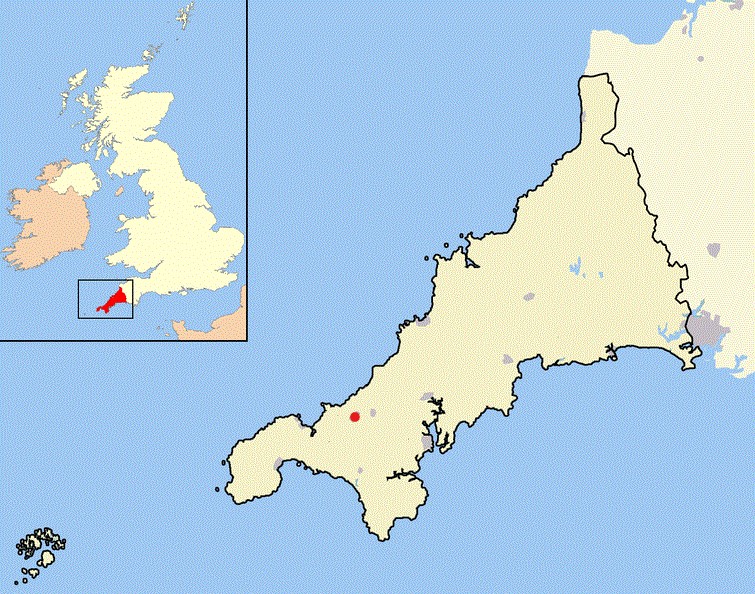

This is the story of the TR14ers Community Dance Charity Limited. An initiative founded in 2005 by David Aynsley when he was a police officer in Camborne, UK to tackle violence and discrimination against children in a disadvantaged neighbourhood.

The story illustrates young people’s transformation through access to social rights from children in need, to children not in need, to children that are NEEDED by their community.[1] The charity continues to offer free dance sessions to children and young people aged 5-18, is run by volunteers supported by paid sessional dance teachers who came through the TR14ers and is managed by a board of directors and trustees appointed at age 16 from within the group.

Deprivation = lack of access to social rights

In 2007, the correlation between living in social housing and the likelihood of living in a disadvantaged neighbourhood was higher in Cornwall than in other parts of the country because Cornwall had less housing stock. Social housing is allocated on a needs basis, therefore individual families have to be more “in need” in Cornwall than in other counties in order to secure a home. The process whereby the most disadvantaged people are concentrated into social housing leads to the concentration of the poor. That is, poor people are funnelled into particularly disadvantaged neighbourhoods.[2]

My police neighbourhood team was constantly deployed to deal with reports of rowdy behaviour, often to find violence and drunkenness amongst and against children, especially girls, who we frequently took to hospital where they were admitted to the children’s ward. Children attended school with terrible hangovers and stinking of alcohol.

The following extracts from a BBC Radio Cornwall news programme[6] give a vivid picture:

Speaker A: “It’s been the worst two and a half years of my life, an absolute nightmare.”

Speaker B: “It is a hard life, you know, you’ve got to watch your house, watch your kids, you know all the time.”

Speaker C: “I think last count was about 18 men, was trying to beat up a young boy 17 or 18. Trying to grab him from the car and pull him out. My children witnessed this from the bedroom windows.”

Speaker D: “All I want to do is get off the estate because I can’t stand living here anymore … I’ve never known teenagers like it.”

The town council held a meeting in which local people and a national politician said the children were the main problem in the town and blamed police for not arresting enough of them. We were very effective at arresting and charging people but no matter how hard we worked at this nothing changed in the community. Police were not dealing with crime, we were dealing with the effects of lack of access to social rights, which arrests and court appearances did not remedy. I knew we had to do things differently but did not know how.

Sometimes children who live in disadvantaged neighbourhoods behave non-rights respectively. We must respond to them rights respectively.

In 2004 I met with the Health Complexity Group (University of Exeter Medical School) who trained my police team in understanding communities as a complex adaptive system and we began to learn to locate ourselves legitimately within the community. All of my team were trained as level 1 sports coaches and ran street games sessions for children in the local parks on behalf of the Health

Three young people, who had previously been in trouble with the police, said on a BBC Radio Cornwall[7] programme recorded in a dance session:

Speaker E: “Before I wouldn’t even speak to a police officer at all but some of them they just have you in stitches. It’s just a laugh.”

Speaker F: “You get to know them, not personally but kind of personally because you get to know them better than seeing them on the road. They’re not taking you home or nothing, they’re just, you can sit down and talk to them and see how they are.”

Speaker G: “If it’s on a Friday night and everyone’s coming out of the pubs and a window gets smashed it’ll be ‘Oh the kids done that’ because they think we’re all hellers [rowdy troublemakers] in Camborne but we’re not.”

Speaker H: “We used to be until this was here. There was nothing, honestly nothing to do in Camborne, well apart from go around town.”

Speaker I: “I love it here, it’s not even in words how much you can say how much I love it.”

As the dance workshops developed the children decided that they wanted to give it an identity. They chose “TR14ers” from Camborne’s postcode – TR14 – because they were too ashamed of where they lived to include the name of the town in their new collective identity. Community shame does not generally feature in executive summaries but it is an important factor in understanding access to social rights in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

As this newfound identity took hold things began to change for the children.[8]

Speaker J: “Normally we’d be drinking, smoking going round the town causing trouble and riot and stuff but now like everyone’s calmed down.”

Speaker K: “Yeah it gets your energy up, that’s the main thing.”

Speaker L: “I’ve seen a really big improvement in myself. I don’t fall out with my family as much. I’m always going to every dance workshop and I love it. I think it’s so good.”

Speaker M: “I’m not as shy as I used to be.”

Speaker N: “It builds your confidence up.”

The effects were noticed in Camborne school, as reported in the Times Educational Supplement:[9]

Fifteen years ago if I’d walked down the corridor with a policeman everyone would have been asking what had happened. Now it’s just commonplace. Now a police officer comes to our regular education welfare and pastoral meetings and we get feedback which is absolutely vital.”

Speaker O: “I had nothing to do before and I ended up getting in trouble with the police because of drinking. Everyone knew Camborne for all the wrong reasons, but now they know it for what we’re doing for the kids. Everyone enjoys it and it stops people doing things like drinking and smoking.” She beams with pride. “And our year group is expecting the best exam results ever.”

Speaker P: “I have been upset and angry because of problems in my family. But I just love dancing. When I come here I feel happy – it affects everything I do. It’s made my life better. I used to answer back at school, but here I’ve learned not to do that. Now I don’t do it at school anymore either. And it’s made me more energetic. Normally I’m lazy, I don’t do anything. But now I’m bouncy. I go to school bouncy.”

The local police commander noticed the improvements and wrote to me on 22 September 2009:

“I have actually used the TR14ers as an example of established diversionary activity for young people in the county to the Audit Commission for their report on us.”

Nevertheless, I was ordered to develop an “exit strategy” from the TR14ers. By now the TR14ers was a constituted group with a bank account and we decided to become a registered company and charity. I continued to work with the charity as a director and volunteer. Things did not go completely smoothly and I took a year out. I returned to find the charity in difficulties and the children more determined than ever to keep it going. Following a devastating theft in 2012 the charity nearly closed. It did not because the remaining directors complied with the legalities and the young people began to step up and lead the sessions.

Young people don’t want to be pawns on a chess board, moved around by someone else. They want to be players.[10]

We have totally recovered from the loss and since 2015 children from 10 years old design and teach their own choreography to groups of up to 60 children aged 5-18. At the age of 15 the young people are invited to join our informal director’s programme and at 16 they are appointed as directors and trustees. As a matter of policy, over 50% of our directors are under 25 (currently 62% are under 25 and 62% are female) and in August 2019 three 16-year-old young women were appointed as company directors and charity trustees. This new dynamic allows the older directors to keep everything legal and the younger ones to keep it interesting for the children. We noticed that children tended to leave at about 14 years old and the young directors decided the sessions needed to be more challenging. They made it so and the effect was immediate. Young people who had left returned and those that reached 14 stayed.

We are now called the TR14ers Community Dance Charity Limited and funded by BBC Children in Need, the National Lottery and the local Police and Crime Commissioner.

In 2019 we were subject to a research project by our old friends in the Health Complexity Group at the University of Exeter Medical School[11] who found:

There is a very strong collective identity associated with being part of the Group. The principles of inclusivity, support, encouragement and development were common themes expressed in the interviews.

In the workshops the young people spoke of feeling able to identify and reject bullying behaviours at school and in friendship groups since becoming a TR14er, having a strong sense of their worth and confidence to try new activities and make new friends.

The overall ethos for the Group is one of children’s rights and the TR14ers are a means to give children and young people access to their social right to the best possible health. Ever since its inception in 2005 the Group delivers the dance sessions free of charge; this ensures that no one is prevented from coming due to financial reasons and that children and young people can choose to attend each week. There is a sense that not charging for the sessions and not having membership terms and conditions creates a strong sense of ownership for the young people, that the TR14ers is “theirs”.

[1] Nurture Development (n.d.), ABCD Thought Leadership/ Taking a strengths-based approach to young people: moving from ‘at risk’ to ‘at promise’: www.nurturedevelopment.org/blog/taking-strengths-based-approach-young-people-moving-risk-promise-part-1/, accessed 29/11/2019.

[2] Cornwall Neighbourhoods for Change (2007), Objective won? CN4C Redruth, p. 9

[3] Davies P., Sorensen E. and Viles S. (2007), West Cornwall profile, Truro Amethyst Information Hub, p. 109.

[4] Cornwall Council (2009), Lower super output area profile, Truro, p. 008B.

[5] Cornwall Children and Young People’s Partnership (2008), Kernow matters, Truro, Cornwall County Council, p. 106.

[6] News (7 January 2006), Antisocial behaviour on the Parc an Tansys Estate, BBC Radio Cornwall

[7] News (11 April 2006), Dance, BBC Radio Cornwall.

[8] News (26 January 2007), Dance, BBC Radio Cornwall.

[9] Times Educational Supplement (20 July 2007), Dance fever. How Hip Hop can help reduce truancy.

[10] Hassall J. (2018), Youth revolution, Rethink Press, p. 47.

[11] National Institute for Health Research (2019), Understanding the sustainable processes and impact of engaging young people in a peer-led dance group, the TR14ers: www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR127482, accessed 29 November 2019.