“Primary schools more inclusive than secondary ones”

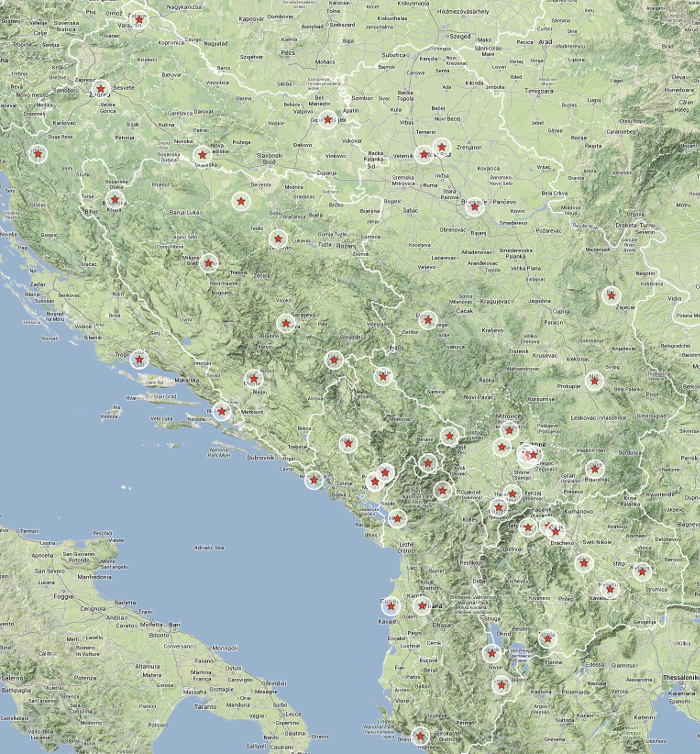

A team of researchers have now completed the two month baseline survey in the 49 pilot schools participating in the project. The survey was designed to capture the views of various stakeholders on the perceived degree of inclusiveness of the schools. Students, teachers, the school project team, parents, local authorities, and where logistically feasible, unenrolled young people, were asked to take part in the survey.

A team of researchers have now completed the two month baseline survey in the 49 pilot schools participating in the project. The survey was designed to capture the views of various stakeholders on the perceived degree of inclusiveness of the schools. Students, teachers, the school project team, parents, local authorities, and where logistically feasible, unenrolled young people, were asked to take part in the survey.

The survey was carried out by a team of researchers affiliated to the LSEE Research Network on Social Cohesion in South Eastern Europe and coordinated by LSE Enterprise, the consulting arm of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The survey led to the development of an ‘Index of Inclusion’ for each school inspired by earlier work carried out by Tony Booth and Mel Ainscow. The Index comprises four dimensions focusing on:

- Inclusive practices for entry into school,

- Inclusion within the school,

- Inclusive teaching and practice approaches,

- Community engagement.

The stakeholders who took part in the survey were asked to answer a number of questions along the four dimensions with answers scored from 1 to 5, where 1 was the lowest level of perceived inclusiveness and 5 was the highest. The index was therefore built on a 1 to 5 scale expressing the overall average score achieved by each school along the four dimensions.

The preliminary results show that the aggregate level of inclusion is similar across the seven beneficiary countries of the project. Looking at the type of schools, it was found that in all countries primary schools were perceived more inclusive than secondary schools, scoring a cross-country average of 3.86 as opposed to 3.69 and 3.68 for secondary general and secondary vocational schools respectively. There is greater variation between individual schools, with the least inclusive school scoring 3.33 and the most inclusive scoring 4.12.

Interestingly, perceptions of inclusion differ between ‘internal stakeholders’ (e.g. teachers) and ‘external stakeholders’ (e.g. parents), with the former systematically rating the schools as more inclusive than the latter, sometimes even by 1 point average or more. Similarly, when asked about ‘factual’ information (e.g. is there a policy in place for reporting bullying?), members of the school project team gave different answers.

These preliminary findings suggest that while there may not be huge differences across countries or across types of school at the aggregate level, there are substantial differences between schools within countries. In addition, the perception of inclusive education varies greatly among stakeholders. This issue should be investigated further as it may signal a disconnect between the formal existence of inclusive practices and their actual implementation and / or impact.

Overall, the surveys provide a wealth of data that will be certainly of great value to inform the various project partners on the baseline upon which the project activities are being implemented.

In doing so, it will challenge many assumptions about school improvement and educational reform. It is about ‘school improvement with attitude'. Hence, school improvement becomes far more than merely a technical process of raising the capacity of schools to generate particular measurable outcomes. It involves dialogues about ethical principles and how these can be related to curricula, approaches to teaching and learning, and the building of relationships within and beyond schools.

In doing so, it will challenge many assumptions about school improvement and educational reform. It is about ‘school improvement with attitude'. Hence, school improvement becomes far more than merely a technical process of raising the capacity of schools to generate particular measurable outcomes. It involves dialogues about ethical principles and how these can be related to curricula, approaches to teaching and learning, and the building of relationships within and beyond schools.