Putting youth work throughout Europe on the map

by Jan Vanhee and Howard Williamson

02/11/2018

It has been quite a slow burner! This is a story as old as the youth partnership itself. But without the partnership, and the implicit or active support of the European Commission and the Council of Europe, youth work in Europe would most likely still be fragmented, unknown, misunderstood, misinterpreted and devoid of any political recognition.

There have, of course, been many players in the process and we would like to thank them all. However, and this may well be disputed by some, the two of us, together with Hanjo Schild and Filip Coussée, have been central drivers of the process – a rather boring constellation of four white men who, almost accidentally, provided a perfect storm of conspiracy and collaboration at critical moments, four musketeers determined to put youth work on the European map. This is unashamedly our story and our tribute to the role of the youth partnership in anchoring the process. It arises out of conversations we have had, and notes we have taken, over the years. History is produced by those who write it, and we know this is just one version, but we still wanted to record it. After all, a perennial question we all ask is how change takes place in the youth field. Drive and determination often disappears without trace. In this story, we got a result and we think it was because of a distinctive constellation of a small group of people in very particular roles, supported by an army of supporters from governments, youth organisations, youth work practice and youth research. You know who you are!

The start of the youth partnership was in fact a covenant between the two partners on one single issue – training and curriculum development for European youth workers and youth leaders. A small steering group was formed to co-ordinate that initiative. The covenant developed and delivered training on the brand-new idea of “European citizenship”, an expression that had not been permitted as recently as 1997 – using, first, the Council of Europe model of long-term training courses (LTTCs) and subsequently constructing a bespoke “training the trainers” course, the ATTE course (2001-03). A philosophy and methodology of “youth work” framed this initiative, though it was not always referred to in these terms.

The start of the partnership coincided with the slow evolution of the European Union White Paper on youth. During the White Paper process, one head of the Youth Unit at the Commission made way for another – Pierre Mairesse. His contribution to putting youth work on the map must not be underestimated, as he supported a range of initiatives undertaken through the youth partnership. The White Paper on youth was launched towards the end of 2001 with its core themes of participation, information, voluntary activities by young people and greater understanding of youth. In the text, there were references to non-formal and informal learning, but no mention of youth work.

However, at the 6th Council of Europe conference of youth ministers responsible for youth, in Thessaloniki in 2002, the decision was made to produce a European portfolio for youth workers and youth leaders. By the time of its release, in 2004, there was the DNA of a “youth worker”, an articulation of some principles and practice that governed their activities, but the naming of that practice as “youth work” and of its practitioners as “youth workers” still remained elusive. Indeed, in the same year, the first Pathways document talked about the “validation and recognition of education, training and learning in the youth field”, not youth work.

The covenant on training and curriculum development had, meanwhile, morphed into a partnership for training, for youth research, and for European-Mediterranean (Euro-Med) co-operation in the youth field – first as three separate strands and later as an integrated partnership. The prospective stronger profiling of youth work arguably got somewhat lost within a wider set of priorities for the partnership. But it had not been forgotten, particularly by Jan, the Flemish Government’s representative in the youth field within both the European Commission and the Council of Europe. And, significantly, the new head of the partnership was Hanjo Schild [see interview with him in this edition of Coyote], a former member of the Commission White Paper team, with a history and commitment to youth work.

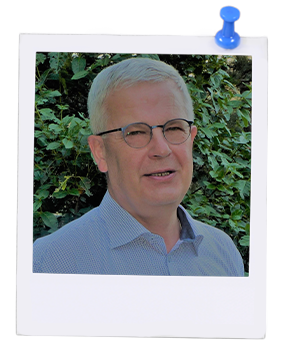

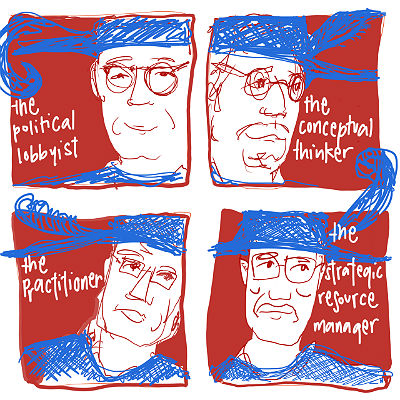

From left field came Filip Coussée, a doctoral student at the University of Gent whose thesis was on youth work in Flanders. Filip had participated in a conference on the history of youth work in the UK and subsequently defended his PhD thesis at the University of Gent, at which Jan was present – and inspired. The ground was set for considering how the history of youth work in Europe (in all its different manifestations) might contribute to the contemporary direction of youth work and wider youth policy. Thought was given to a modest seminar exploring such a theme. Filip mentioned this to Howard, who offered his support. Filip, in reflecting on different traditions and directions for youth work (see Coyote extra, July 2010) has contrasted the Saint (Don Bosco), the Poet (Albrecht Rodenbach), the Lord (Baden Powell) and the Cardinal (Jozef Cardijn). One might cautiously suggest that another group of four men anchored European youth work developments a century later: the political lobbyist (Jan), the strategic resource manager (Hanjo), the conceptual thinker (Filip) and the practitioner (Howard). Each offered much more than that single characterisation, but it was that blend that made things happen.

Critically, however, this work has reached further and penetrated deeper than just an academic exercise. The first key moment was in 2010 during Belgium’s presidency of the European Union. Jan orchestrated a whole week of attention to youth work, first through a 3rd history workshop (though this time it was called a conference) and then through the 1st European Youth Work Convention. The latter produced a Declaration celebrating the diversity of youth work in all its forms, from the work of self-governed youth organisations to outreach and detached work on the streets. The Declaration, in turn, provided the launch pad for the first EU Resolution on Youth Work, endorsed by the Council of Ministers for Youth in the autumn of 2010.

Further history workshops took place, in Estonia and Finland, as well as developments towards the recognition of non-formal education and learning and youth work in Europe through “Pathways 2.0, Getting there!” (2011). Given the complementarity of formal, non-formal and informal learning, it was felt that the political process for a better recognition and validation of youth work and non-formal learning/education in the youth field needed to be reinforced by a joint strategy – what came to be known as the “Strasbourg process”. Such a process was directed towards the need for a strong and sustainable political commitment to strengthen support for youth work in all its forms. Around the same time, the partnership was instrumental in supporting a pilot programme for a Master’s in European Youth Studies (MA EYS), led by the late Lynne Chisholm, in which youth work featured prominently. Furthermore, the German national agency for European youth programmes celebrated 25 years of Jugend für Europa in 2013, during which there was a workshop considering a follow-up to the 1st European Youth Work Convention.

However, towards 2015, it was clear that articulating (and advocating) the diversity of youth work often produced even further confusion in the minds of policy makers and politicians. As Belgium’s chairmanship of the Council of Europe appeared on the horizon, Jan saw a case for a 2nd European Youth Work Convention, one that this time considered “common ground”: if youth work was characterised by such diversity in practice and methodology, what was it that those who considered themselves to be youth workers actually shared? Were self-governed youth organisations and detached youth workers, and all those other forms of youth work in between (open youth work, youth clubs, youth projects, issue-based youth work, advocacy campaigns, and more) really working on any “common ground”?

Jan asked Howard to prepare a position paper, entitled “Finding common ground: mapping and scanning the horizons for youth work in Europe”. The partnership, through Hanjo, was pivotal in contributing to the wider preparatory work. The 2nd European Youth Work Convention, involving representatives from the 47 countries of the Council of Europe (and guests from elsewhere), interrogated youth work’s common ground, concluding that all youth work sought to create and defend spaces for young people’s autonomy and self-determination while simultaneously providing bridges for young people to move forward, positively and purposefully, to the next steps in their lives. This was enshrined in a 2nd European Youth Work Declaration, with the caveat that future challenges for youth work will crystallise around working in an increasingly multicultural Europe and getting to grips with the pervasive impact of digital technology.

Just as the 1st Declaration had been developed into a formal political resolution within the European Union, so the 2nd Declaration was subsequently shaped into a formal political recommendation within the Council of Europe, ratified by its Committee of Ministers in May 2017. Within that recommendation lay the proposal for the formation, subsequently initiated by the Council of Europe Youth Department, of an ad hoc high-level task force on youth work, to take its agenda forward. Elsewhere, EU Erasmus+ projects and collaborative activity between EU national agencies are now also advancing the case for, and cause of, youth work throughout Europe.

Moreover, with the considerable momentum established, there was already talk of a 3rd European Youth Work Convention, planned for Germany in 2020, by which time the history series will have run its course. The final publication from that series, on the background to and work of pan-European and international youth work organisations, will have been produced. The momentum that started with historical understanding, moved through professional debate and direction and then secured political ratification, now needs consolidation and development. And so the circle turns.

What does this tell us? That both people and partnerships matter. There have been some key individuals along this road but their endeavour and application would have been in vain without structural support from a number of quarters, including the two key European institutions (the European Commission and the Council of Europe) but, arguably, most notably the youth partnership.